- A Collective Open Apology for Response to Racist Language in the Women and Psychedelics Forum - December 3, 2018

- Psychedelic Justice:Disrupting the Cultural Default Mode Network - September 12, 2018

- How Psychedelic Science Privileges Some, Neglects Others, and Limits Us All - July 25, 2017

People want accountability from the science and the funders around equal access and open science

The psychedelic science movement is facing a crossroads. People want accountability from the science and the funders around equal access and open science. Tangible tension is arising between those who are seeking to profit from the science and those who prioritize healing and social justice. Navigating fraught lines between the mainstream and the marginalized is never easy. I work in academic medicine, leading federally-funded research in collaboration with transgender communities on issues related to health disparities. We strive to put social justice at the center of our science. As an academic, I came to the renaissance in psychedelic science fairly recently; I was honored to be included among the very first graduates of the Certificate in Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies and Research at the California Institute of Integral Studies. This training was completely and positively transformative. However, as I digested the scientific literature and engaged in dialogue with my cohort, I was surprised by the lack of social justice analysis in the field as a whole.

the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) accepted one million dollars from the Mercer Family Foundation

Then, in early 2018, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) accepted one million dollars from the Mercer Family Foundation. To provide some context, the Mercer Family Foundation owns large stakes in several conservative think tanks and racist alt-right groups, including Breitbart and the Heritage Foundation. They gave $25 million to the Trump campaign in 2016 and financially backed illegal data mining through Cambridge Analytica, playing a critical role in his election. The Mercers continued to vehemently support Trump even after the release of the infamous recording of Trump bragging about grabbing women by the genitals. Further, Rebekah Mercer has been under public pressure from hundreds of scientists to step down from the board of the American History Museum due to her vocal rejection of the mounting scientific evidence of climate change. I could go on (but I won’t).

Personally, I was absolutely floored and appalled when the acceptance of this donation was announced so proudly by MAPS. I was moved to write an emotional email to a Women in Psychedelics listserv about my objections to seek dialogue with people whose opinions I trusted. I won’t rehash those conversations but suffice it to say that they changed the questions I was asking myself about who I am within this movement and what values are truly at the center of this science.

Bett Williams writes in The Wild Kindness: “Many argue that such compromises and deals with the devil are necessary in order to destigmatize psychedelics in the minds of the mainstream populace. My question has always been: To achieve what, exactly, and for whom?”

As a result of these conversations, I realized that the shock I felt came from an unexamined assumption I had been making: that social justice is inherently part of the agenda of psychedelic science. In retrospect, I can see how naive this assumption was. I began to grapple with a new question: Should psychedelic science necessarily be concerned with social justice issues?

For me, the answer depends on what the ultimate goal of the science truly is. The legalization agenda must not aim (or even appear to aim) to disrupt any existing hierarchies or value systems currently upheld by our government, lest the government perceive our science to be a threat to the status quo. There is no such thing as science outside of a political context or without a political lens. Science is constantly being shaped by social forces, unexamined assumptions, funding, and legal contexts.

Daniel Dennett wrote in Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: “There is no such thing as philosophy-free science; there is only science whose philosophical baggage is taken on board without examination.”

Our values shape the scientific questions we ask, the ways that we design our research, how we interpret the conclusions and who we intend to serve. We replicate our social programming in our psychedelic science. An example of this replication is the requirement that psychedelic-assisted therapy teams must be comprised of one man and one woman. This protocol assumes that clients need to have their biological parents reflected by the therapy team. However, there is absolutely no empirical evidence supporting this assumption, which does not account for people who are raised by gay couples, transgender people, or single parents. It does not take into consideration the client’s presenting issues or personal preferences. Further, are the required male/female therapist pairs necessarily cisgender (meaning, not transgender)? Is there space in this model for transgender people or non-binary people to serve as therapists?

Without questioning, we replicate assumptions about families, sexuality, gender, race, and often by default, we center the voices of white men in our conversations. Do we ultimately want our psychedelic science to reinforce our cultural assumptions, or do we want to revolutionize them? Personally, I am interested in being part of the revolution. In order to succeed, though, we must make the goals of the revolution clear and compelling. Like psychedelic justice, for example. Psychedelic justice is about disrupting our default mode network on a cultural level.

Let’s get clearer about the types of questions we are asking, and why. Which scientific questions reinforce our cultural assumptions and which ones revolutionize them?

“what are the effects of psychedelics on the brain?” are critical because they help us advance the foundation of our science, but they don’t tell us what to do with it

Different questions create different types of knowledge; this is an idea introduced in the ‘60s by Habermas, a German philosopher and critical theorist. Technical questions, like “what are the effects of psychedelics on the brain?” are critical because they help us advance the foundation of our science, but they don’t tell us what to do with it. Interpretive questions can help us understand the implications of our technical findings. They help us generate hypotheses about the importance of mystical experiences, for example. Interpretive questions might explore psychedelic use in different cultures so we can learn from them to inform our own practices.

Emancipatory questions are interested in human liberation, even salvation. Questions such as: How can psychedelics help us address the root causes of trauma? How might psychedelics foster resilience, so that we can all stay engaged in the revolution? How can psychedelic science help us save ourselves from the destructive path we are on? How can psychedelics help us to be more ethical, more loving, bring more justice into the world?

These might seem like lofty questions, but if we aren’t asking them, what is the point? We must go beyond just trying to recruit diverse populations into studies that have been designed by straight white people for straight white people. We need research that is truly grounded in our communities, with full participation by the communities themselves.

The Western medical framework tends to devalue emancipatory approaches to knowledge production. In psychedelic science, I think we are missing the emancipatory perspective. We need it to be truly integrated with the technical and the interpretive for the revolution we envision to actually manifest as a result of our science. We need this integration in order to raise the level of the questions we are asking about what is possible. Using an integrated, emancipatory framework we might ask “how do we disrupt the default mode network of an entire culture?”

Let’s revisit the initial question: Should psychedelic science necessarily be concerned with social justice issues? Some people might say no. We are not just one psychedelic community anymore. Some of us will choose to build bridges with people who espouse racist agendas for money and some of us will help rich people get richer by co-opting our medicines. Some of us are interested in radical, cultural transformation. Our values shape the questions we ask.

In Emergent Strategy, adrienne maree brown asks,“how do we collaborate on the process of dreaming and visioning and implementing a world that works for more people?”

We must bring justice to our own psychedelic communities, if we expect to revolutionize society with psychedelics

We must bring justice to our own psychedelic communities, if we expect to revolutionize society with psychedelics. We are not there yet. We do not yet have examples of how to create psychedelic community as a microcosm of what we want to see in the world. There is no utopia. We have glimpses of it in some spaces, discussions that center the voices of people of color, women, queer people, and indigenous people, the celebratory aspects of psychedelic festivals, Burning Man’s gifting culture, the healing spaces at Lightning in a Bottle, Women’s Visionary Congress, and we can also clearly see where we are still challenged.

I praise our communities for our honesty and longing for wholeness, for not settling for the “almost” or the “could be.” Psychedelics themselves have provided us with a vision of what is possible, and we will not settle for anything less than fulfillment of that vision. Psychedelic justice is based on collaborative ideation, the birthing of new ideas and sharing that process collectively. The Statement on Open Science and Open Praxis is a beautiful attempt at that. The more people who co-create the future, the more people whose concerns will be addressed at a foundational level. It is up to us to create alternative conversations. Instead of calling each other out, let’s create spaces to find each other and participate. Psychedelic justice is about creating alternatives rather than perpetually re-creating the system.

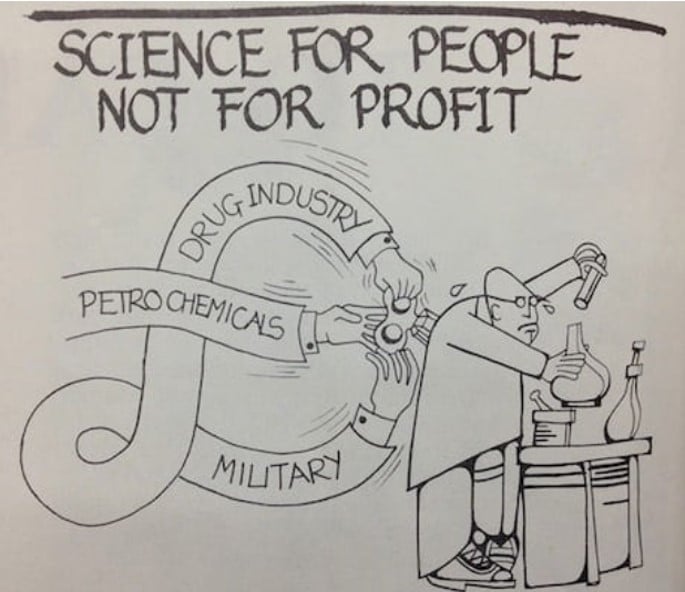

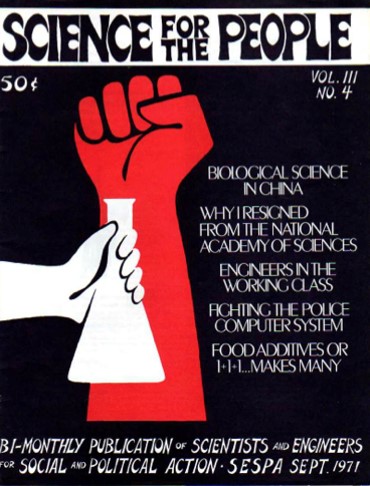

An attempt at this was made in the ‘60s with Science for the People, a non-hierarchical radical group of scientists and activists that sought to resist the militarization of scientific research and the corporate control of research agendas. These fundamental questions of power and ideology remain in science today, and Science for the People is being revitalized. I say we need a chapter called Psychedelics for the People!

A sacred rage is building. Our psychedelic hearts are capable of profound bliss and ecstatic reverence, and they also feel a deep passionate longing for what we know is possible. That longing is growing from an inner sense of disquiet to a full-on sacred rage. Let us remember that this collective rage is a beginning, not the destination. Its purpose is to guide us to higher, more connected ways of living. A new paradigm needs a new lexicon. We are introducing new ideas, new terms, new questions that will help us to create the revolution together. We are all being invited to participate.

Note:

This paper was presented at Cultural and Political Perspectives in Psychedelic Science, a symposium promoted by Chacruna and the East-West Psychology Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS), San Francisco, August 18th and 19th, 2018.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?