- Rethinking Psychedelic Risk - February 26, 2026

- Plant Medicine in Mexico: From Traditional Use to Psychedelic Therapy - August 5, 2025

- The Enchanted Science of Jurema: DMT at the Root of Afro-Amerindian Rituals in Brazil - June 20, 2025

- The Use of Psychoactive Plants in the Americas - September 11, 2019

Beatriz Caiuby Labate & Sandra Lucia Goulart (eds.)

Abstract:

This book tackles original ethnographies about various types of use of psychoactive plants, including ayahuasca, magic mushrooms, jurema, coca, tobacco, toé, Cannabis, snuff, sananga, kambô, yopo, timbó, and beverages such as caxiri. The chapters present a diversity of notions and practices relative to the use of such plants, highlighting the contexts of indigenous and non-indigenous uses, as well as intermediations and complex fluxes between them. The contributions discuss various themes, such as shamanism, agency, indigenous thought, gender, and performance. The different types of consumption of these substances, made by local and transnational populations, allow us to rethink classic anthropological categories such as ritual, sacred and profane, and healing. Pointing to the complexity of the contexts in which the uses of these psychoactive plants occur, this books also sheds light on the debate about the need for drug policy reform.

Editor’s Biographies:

Dr. Beatriz Caiuby Labate (Bia Labate) is a queer Brazilian anthropologist who immigrated to the U.S. in 2017. She has a Ph.D. in social anthropology from the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Brazil. Her main areas of interest are the study of plant medicines, drug policy, shamanism, ritual, and religion. She is Executive Director of the Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicines (https://chacruna.net), an organization that provides public education about psychedelic plant medicines and promotes a bridge between the ceremonial use of sacred plants and psychedelic science. She is Adjunct Faculty at the East-West Psychology Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) in San Francisco, and Visiting Professor at the Center for Research and Post Graduate Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS) in Guadalajara. She is also Public Education and Culture Specialist at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). She is co-founder of the Interdisciplinary Group for Psychoactive Studies (NEIP) in Brazil, and editor of NEIP’s website (http://www.neip.info), as well as editor of the Mexican blog Drugs, Politics, and Culture (http://drogaspoliticacultura.net). She is author, co-author, and co-editor of twenty-one books, one special-edition journal, and several peer-reviewed articles (http://bialabate.net).

Sandra Lucia Goulart has a PhD in social sciences from Unicamp (2004), a master’s degree in social anthropology from the University of São Paulo (1996), and a degree in social sciences from USP (1989). Her master’s and doctoral research addresses the Brazilian religions that use the psychoactive drink ayahuasca. Goulart researches the use of drugs in different social contexts. She is co-author of the books Drugs, Public Policies and Consumers (2016); Drugs and Culture: New Perspectives (2008), and The Ritual Use of Power Plants (2005). Currently, Goulart is a professor at the Cásper Líbero College (SP), where she teaches anthropology for journalism, advertising and propaganda courses.

Table of contents

Foreword

Esther Jean Langdon

Introduction

Sandra Lucia Goulart and Beatriz Labate

Part I: Indigenous Uses

1. What Has Tobacco Shown to You? Drawings and Artefacts From Wauja Shamanic Visions, Upper Xingu

Aristoteles Barcelos Neto

Tobacco is the most widespread psychoactive plant cultivated in the Americas. Historically, its cultivation is known from the Bay of Chesapeake to the Plata Basin, spreading throughout the vastness of Amazonia, Mesoamerica, the Caribbean, and the Atlantic tropical coast of South America. Tobacco is seen by numerous indigenous peoples of Lowland South America, including the Wauja of the Upper Xingu, as a powerful agent for transformation (Russel & Rahman 2015, p. 6). As a central topic of this chapter, the notion of transformation is approached in light of its horizon of visual expression and mythic exegesis. The possibilities of seeing and acting in the worlds of the spiritual beings, of uncovering people’s occult intentions and secret actions, and of making divinations, are among the most potent reasons that motivate someone to get initiated in the tobacco shamanism of the Upper Xingu. What exactly does tobacco smoking show to Xinguano shamans? How do they translate to the non-initiated the things and beings they see in their dreams and trances? These are some of the questions this chapter intends to answer.

2. The Wander Women: Connections Between Tobacco Snuff and Jarawara Feminine Agencies

Fabiana Maizza

Based on my ethnography with the Jarawara women, I will explore the concepts of “taking” (towaka), “going” (toka), “going back” (kama), “bringing back” (kaki), and “carrying” (weye); all very important to the everyday life of people. My argument will be constructed through the description of the “girls’ initiation ritual” (mariná) and its effects in the composition of a feminine agency that could be possibly examined in reference to the ideas of “leading” and “being led.” During such rituals, the consumption of tobacco snuff, as well as an oneiric disposition, seems to reveal to the girls the capacities that bodies and souls have to be led, an ability also associated with shamans. I will be interested to think how a certain Jarawara notion of “lightness” would involve movement—taking, carrying, leading, being taken—in order to forge connections between the tobacco snuff and feminine agencies.

3. Manioc’s Seduction

Joana Cabral de Oliveira

The Wajãpi—an Amerindian group who inhabit the region of Jari River in Brazil—like other Tupi groups, are famous for their caxiri (a manic beer) meetings. The Wajãpi women produce the fermented drink with some tuberous roots (like manioc, sweet potato, and taro) and also with corn, but the most exemplar caxiri is made with bitter manioc. They used to drink it in special contexts, following rules of etiquette and patterns of behavior through which they reach the -ka’u state (drunkenness, heaviness, and fullness). However, in the circumscribed context of drunkeness, the manioc and the other plants are not considered sacred. The caxiri’s meetings are not rituals or related to shamanic actions. Looking to the only psychoactive substance ingested by the Wajãpi people, this paper aims to present an ethnographic reflection about the caxiri’s meetings to raise questions about the limits of the “sacred plants” concept. My approach is aligned with an anthropology “beyond human,” and the idea of “multi-species ethnography” to bring a reverse perspective, where the manioc is the subject that acts upon humans through seduction.

4. Hib’ah Wed: Coca and Smoke Circles Among the Hupd’äh People

Danilo Paiva Ramos

At sunset, when the sound of the crusher can be heard all over the village, the Hupd’äh seniors may be seen walking slowly to greet each other and then to sit on their stools to form the coca circles. While the tobacco cigarette smoke spreads through the night air, green coca powder is poured into their mouths. During their conversations, myths are told, spells are taught, and walks through the jungle paths are talked about. Whispering spells to their cigarettes or bowls, some participants perform shamanic actions to cure and protect people. In this study, the rounds of coca of the Hupd’äh, and of many indigenous people of the Northwest Amazonia region, are regarded as contexts in which associating mythic and shamanic agencies constitutes a particular relational form that situates participants in fields of perception and action. Against the backdrop of the violent and totalitarian War on Drugs of the Brazilian State in this region, this study highlights how new comprehensive descriptions on the coca use of indigenous people may be important in order to build public policies to improve and protect these traditional practices.

5. The Plant of Anger: Timbó and Poisoning among the Suruwaha from the Purus River

Miguel Aparicio

In the houses beside the Jukihi stream in the Purus River valley, people say, “the spirit of timbó is a shaman.” When we deepen into the subjectivation regimes of the Suruwaha, an indigenous group in Western Amazonia, we discover the movements of capture that the timbó (Deguelia utilis), an ichthyotoxic plant, develops with the true-humans (jadawa). Capable of producing a split in the person, transforming him into an ex-human “soul” and an inhuman predator, timbó places humans in the condition of prey par excellence, and challenges our perceptions of death, suicide, and irruption of nonhumans into human life. Attacked by the timbó, the Suruwaha dissolve the boundaries between the desire to die and the desire to kill: In conflictive situations, someone runs to ingest the lethal poison, and his angry heart draws others to the poisoning. The dead are accused of witchcraft because of causing further death. Crossing the threshold of the world of the living and the dead on an agonizing path, those killed by timbó undergo a transformation into fishes, fleeing from the chase of the jaguars of timbó, until they reach the waters of thunder. For the living, thunder expresses the longing and anger of the poisoned. The Suruwaha of the last generations experience dramatically the emergence of a new way of death, opened by the spirit of timbó. Suruwaha shamanism points to an interstice where diverse worlds connect. Moving on the threshold of these worlds, humans flee from the insistence of a shaman-plant that insists on capturing them.

6. Toé (Brugmansia Suaveolens): The Path of Night and Day

Glenn Shepard

Brugmansia suaveolens, called toé in the Peruvian Amazon, is known to the Matsigenka people as hayapa, saaro, or simply kepigari (poison, intoxicant). The Matsigenka consider it to be the most toxic, and perforce, the most powerful, medicinal and spiritual plant of their pharmacopeia. Belonging to the Solanaceae, or Nightshade family, Brugmansia contains the potent alkaloids atropine and scopolamine, used to this day in biomedicine. Unlike ayahuasca, which is taken often in group ceremonies or by both patient and healer, Brugmansia is used rarely, only by the patient. Though many Matsigenka individuals have taken Brugmansia at some time in their life, frequent use is considered dangerous, tempting the user with the dark secrets of sorcery, and sometimes leading to insanity or death. Brugmansia, for the Matsigenka, is the last resort to the highest medical authority, reserved for only the most serious cases. This chapter presents an overview of the pharmacology and ethnobotany of Brugmansia, reviews Matsigenka concepts and traditional uses of the plant, and presents direct observations of the plant’s miraculous curing powers, as well as the dangers associated with its improper use.

7. Veladas and Flowers: Ritual use of Psychoactive Mushrooms Among the Mazatec

Sérgio Brissac

The indigenous Mazatec people makes ritual use of psychoactive mushrooms, called by them, reverentially, honguitos. This chapter is based on ethnographic work centered in Huautla de Jimenez, on Sierra Mazateca in the State of Oaxaca, Mexico, during doctoral research. Some veladas will be described; they are nocturnal rites with the use of mushrooms, directed by a chjota chjine, a man or woman of knowledge, ritual, and healing expertise. The chapter seeks an approach to the experience of the Mazatecs themselves in their rites with mushrooms, from the life stories of three chjota chjine, focusing on the experiences associated with the veladas at the beginning of their work as healing experts. Teresa, who lives in Huautla, despite many people looking for her, and asking for her help as a guide in healing rites with honguitos, she affirms that she is not a chjota chjine. Tibúrcio, who dwells in a rural place called Agua de Niño, describes his beginnings as a call to familiarity with “Our Lord.” Melésio, from Agua Platanillo, another community in the fields, recalls his initial experiences under the tension between the desire for wealth and serving the poor. After following the course of these narratives, it will be possible to detect some common axes in these different paths.

Part II: Usos Indígenas e Não indígenas: Fluxos, Interfaces e

Distinções

8. The Use of Marijuana in the Context of its Criminalization in Brazil, 1930

Thamires Regina Sarti Ribeiro Moreira

In 1938, the newspaper A Noite reported the arrest of a “pope of barbarous rites” in Rio de Janeiro. José Soares was caught while performing “exorcism” on “an under-aged girl.” A branch of herb was found in his house, later identified by police as marijuana. The Commissioner of Section Toxics and Mystification directed itself to the establishment of the “pai-de-santo” in order to investigate a complaint of “macumba.” Upon arriving at the site, not only was the complaint of mystification imposed, but a banned toxic was also found, which made João’s situation even more severe. It was not a coincidence; the “mystification” and the toxin were understood in the same social problem key, which connected both in the same repressive practice. The report featured an interview in which Joseph defended macumba as a religion, “as good as any other” and which had been inherited from his grandparents. He also defended the “diamba,” (Cannabis) which he knew by the name of “jabotá,” extolling its medicinal and sacred functions. Finally, he claimed to be unaware of the illegality of the plant. The use of this herb may be as old as the religion; it was its criminalization that was recent. Even if the lack of knowledge about the plant’s illegality was not true, this argument could be tried in order to prevent the episode from becoming, in his words, a “big deal.”

9. The Wild Pigs, the Lightheaded-Tobacco and the Bitter-Water: Kraho Reflections on Two Psychoactive Substances

Ian Packer

Amerindian people’s appreciation of substances that can alter perception is well known. Many ethnographies have been devoted to the ritual or everyday use they make of fermented beverages and plants such as ayahuasca, tobacco, coca, and toé, among many others, all of them native to the American continent. Little is known, however, of the use these people make of psychoactive substances produced and consumed by non-indigenous people that reached them through outside contact. There are few studies, for example, on the indigenous consumption of alcoholic drinks such as sugarcane liquor (cachaça), and virtually nothing on the use of marijuana (Cannabis sativa). Through the analysis of some Krahô narratives and reflections on marijuana, this chapter seeks to understand the place occupied by this plant in their thought, and thus understand native conceptions on its effects and its differences from another psychoactive substance, cachaça. Similarly, the assembled material also makes it possible to glimpse something of the indigenous perspective on the question of the legality versus illegality of drugs, a debate that permeates our society in different ways.

10. Mambe and Ambil Between Murui-muina Indigenous of the Colombian Amazon: Sacred Plants and Political Action

Marco Tobón

Since 2000, the Colombian war has brought the armed dynamic to indigenous territories of the Murui-Muina in the Colombian Amazon. This reality was seen by indigenous people through autonomous cultural practices marked by the consumption of sacred plants, such as mambe and ambil of tobacco. The consumption of mambe (leaves of coca pounded and mixed with embaúba ash) and ambil of tobacco(mixture of tobacco with vegetable salts) sets out a conceptual structure that engages in ethical and policy actions. The mutual relationship between the Murui-Muina andthecoca and tobacco plants founded an integral cultural field of religious experience, medical practices, moral conduct, body care, collective protection and, in the current scenario, guiding instruments of collective actions against the armed actors in the Colombian war that occupy their territory.

11. La Dieta: Ayahuasca and the Western Reinvention of Indigenous Amazonian Food Shamanism

Alex K. Gearin & Beatriz Caiuby Labate

We undertake an unorthodox approach and investigate dietary and behavioral restrictions in the practice of Western ayahuasca drinking in comparison to indigenous Amazonian practices of dieting often believed to be the source of the “Western ayahuasca dieta.” Combining readings of Amazonian ethnography with the authors’ ethnographic research in neoshamanic contexts of ayahuasca drinking in Australia, the United States, and Peru, we consider how the practice of ayahuasca dieting has become detached from indigenous cosmologies and sanitized into a series of techniques that Westerners employ in the hope of attaining certain psychological and spiritual traits. We consider the dislocation of ayahuasca from indigenous cosmologies of reciprocity and predation—in which issues of human-environment relations are sanctioned and produced via shamanism—to a Western practice where “plant spirits” or “plant medicines” from an indigenous “tradition” meet the demands of the individual’s self-healing and personal development. This is explored by analyzing key examples of indigenous food shamanism among indigenous Amazonian cultures in contrast to Western neoshamanic explanatory models of dieting, prescriptions to drink ayahuasca, and to the emic concept of “integration.” The comparison suggests how contradictions and limitations may occur when spiritual beliefs grounded in radically different social, economic, and cosmological environments are appropriated and reinvented.

12. Navigating the Astral: Flows and Transformations in the Rituals of Nixi Pae

Guilherme Pinho Meneses

This chapter aims to reflect on a movement underway in the Kaxinawá Indigenous Land of Rio Humaitá driven by the use of nixi pae (ayahuasca) and other “medicines of the forest.” This movement, based on the occasion of their festivals, has triggered a series of changes in the “traditions” and “culture” of this people. In outlining the assemblages between the actants involved in this issue in the cosmologies of Amerindian peoples, ayahuasca religions, and New Age movements, all intertwined in specific ways, we enter into a cosmo-political dimension of the debate, in which the nixi pae appears as a fundamental non-human mediator in mobilizing sharing networks, confrontations, and alliances.

13. Snuff and Sananga: Medicines and Mediations Between Indigenous Settlements and Urban Centers

Aline Ferreira Oliveira

This chapter reflects on forest medicines, highlighting snuff (fine-ground tobacco with ash) and sananga ( “forest eye drops”), and their interfaces between indigenous and non-indigenous uses. Recently, Pano indigenous people from Acre (Brazil), mainly the Huni Kuin (Kaxinawá), Yawanawa, and Noke Kuin (Katukina), have been “introducing their culture” to the Nawa ( White people). They do this either in the festivals that take place every year in their settlements or in the cities, or by running nixi pae or uni (ayahuasca) rituals in holistic spaces, farms, churches of Santo Daime, several ayahuasca religious centers, or houses of practitioners of neoshamanism. The paper, therefore, analyzes the varied uses of these “medicines” and the translations operant in this flow between (indigenous) settlement and city, pointing to similarities and differences in the Nawa uses and contemporary indigenous ways. Due to translations of rituals, festivities, and concepts, uses and meanings are multiplied in this transit, raising the question of how the expansion of Pano shamanism creates new transformative and performative dynamics. We will introduce snuff, kambô and sananga as mediators in these networks woven by liana, seeking to understand them in relation to forest science, populated by beings and intelligences that interact in a flow of forces.

14. The Forest Medicines: The Ritual Consumption of Psychoactive Substances in Santo Daime’s Circuit

Saulo Conde Fernandes

After contact with some Acrean indigenous populations, a substantial number of Santo Daime’s adepts adopted cultural practices that involve psychoactive substances usage beyond ayahuasca (daime) and cannabis (Santa Maria) These are notably three: the rapés (tobacco snuff combined with other plants); sananga (“forest eyedrops,”: a liquid made with different species of plant); and kambô (“frog venom,”: an arboreal frog, Phyllomedusa bicolor, secretion). These substances are consumed together in rituals known by their generic names, “Pajelança” or “Caboclança,” whose protagonists are Acre’s indigenous people or “natives,” and in rituals invented by daimista leaders (“Eagle Flight,” “Humming Bird Flight”); in both cases the potential participants are in Santo Daime’s circuit. Classified as “forest medicines” and credited as capable of healing physically and spiritually, these substances also began to be used in everyday life, during daimista work breaks (rapé and sananga), or in specific situations with small groups associated with themselves. In this cultural interaction and sustaining or inventing of traditions territory, issues arise such as the adoption of cannabis by indigenous people and the unofficial use of kambô in urban centers.

15. The II World Ayahuasca Conference: New Local and Global Configurations

Sandra Lucia Goulart & Beatriz Caiuby Labate

This chapter provides a panorama of the II World Ayahuasca Conference (II AYA), held in 2016, in Rio Branco, Acre, organized by the Spanish NGO ICEERS (International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research & Service). Participants included scholars from different scientific areas, representatives of Amazonian ayahuasca religions, leaders of ayahuasca religions from Europe, members of neo-ayahuasca groups, representatives of vegetalist centers, and members of 15 indigenous groups. The authors identify and analyze the subjects and groups, as well as the themes, debates, conflicts, alliances, and political strategies most in evidence during the event. Goulart and Labate pay special attention to the indigenous presence and protagonism during the conference, showing how this new fact transforms the relations and classifications comprising the Brazilian ayahuasca scenario. Among the different issues linked to ayahuasca, some of the discussions that most provoked controversies were “native” versus “scientific” knowledge, the debates surrounding the patrimonialization of ayahuasca, and the accusations concerning the commercialization and desacralization of the drink. The conference demonstrated that, from the Global South to north, there exist “various ayahuascas,” and that the diverse agents linked to the drink compete among themselves for the status of being the most authentic. In sum, through the analysis of the conference, the chapter reflects on the current configurations of the global ayahuasca field and its main controversies.

16. Contexts and Uses of Jurema

Rodrigo de Azeredo Grünewald, Robson Savoldi

In Brazil, some species of plants are called Jurema. In several ritual contexts, this name is applied to drinks made from these plants, but also for others not prepared from them. Since the colonial period, the ritual use of jurema among indigenous populations is recorded in Brazil. Besides these records, “jurema” is a term traditionally used also in Catimbó and Umbanda. More recently, contemporary experiments now carried out by psychonauts have improved methods of using the plant in order to obtain the best extraction of Dimethyltryptamine (DMT). Such experiences are undertaken with an almost total freedom in the creations of settings for these rituals, which are periodically re-elaborated by individuals who meet aligned groups. This chapter presents that broad universe of juremas, but with greater focus on the psychonautic uses, since these are less described in the literature.

17. Notes on the Contemporary Uses of Peyote and Sacred Fire of Itzachilatlan

Isabel Santana de Rose

This chapter is divided into three parts. The first one is an expanded review of the book Peyote: History, Tradition, Politics and Conservation, edited by Beatriz Caiuby Labate and Clancy Cavnar (2016). Here, I address some of the transversal themes brought up in this interdisciplinary collection. Those include the environmental debate about peyote’s preservation and conservation; the legal discussions surrounding this cactus in Mexico, Canada, and the United States; the challenges regarding how to balance environmental issues; and issues concerning human and Indigenous rights and religious freedom. The second part of the chapter is a presentation of the Sacred Fire of Itzachilatlan, including the group’s history, its most important rituals, some of Sacred Fire’s main cosmological features, and comments on the academic research conducted in Brazil about this movement. Finally, in the third part, I discuss the request recently placed by Sacred Fire’s Brazilian leaders to the National Council on Drug Policies, Conselho Nacional de Política sobre Drogas (CONAD), regarding the legalization of the ritual and religious use of peyote in this country. The different debates present in the three sections of this chapter, and the connections between them, aim to fulfill a gap regarding Brazilian discussions and publications about both Sacred Fire and peyote’s uses.

Launch Tapera Taperá São Paulo

Congresso da Associação Portuguesa de Antropologia

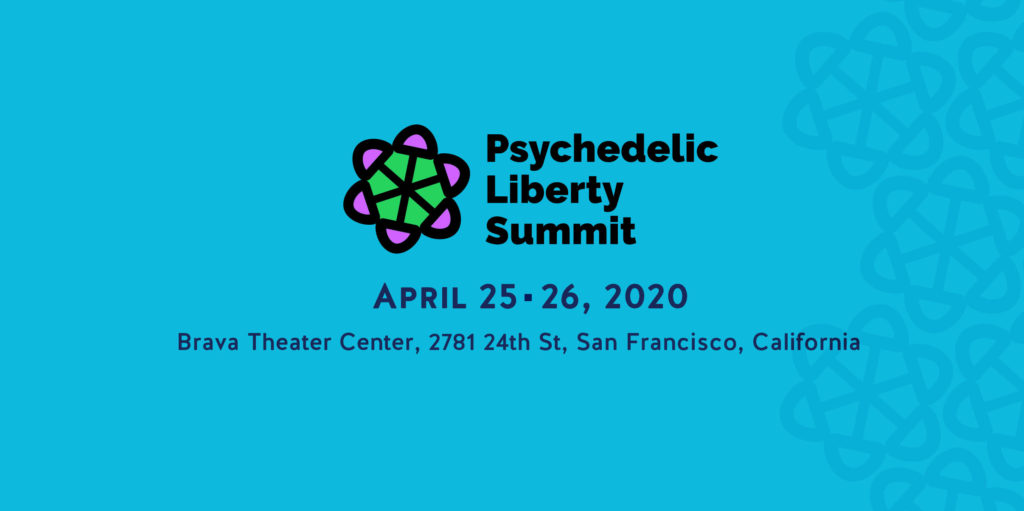

Join us at the Psychedelic Liberty Summit

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?