- When Jesus Meets Ayahuasca: Sample Texts from Christ Returns From the Jungle - February 1, 2022

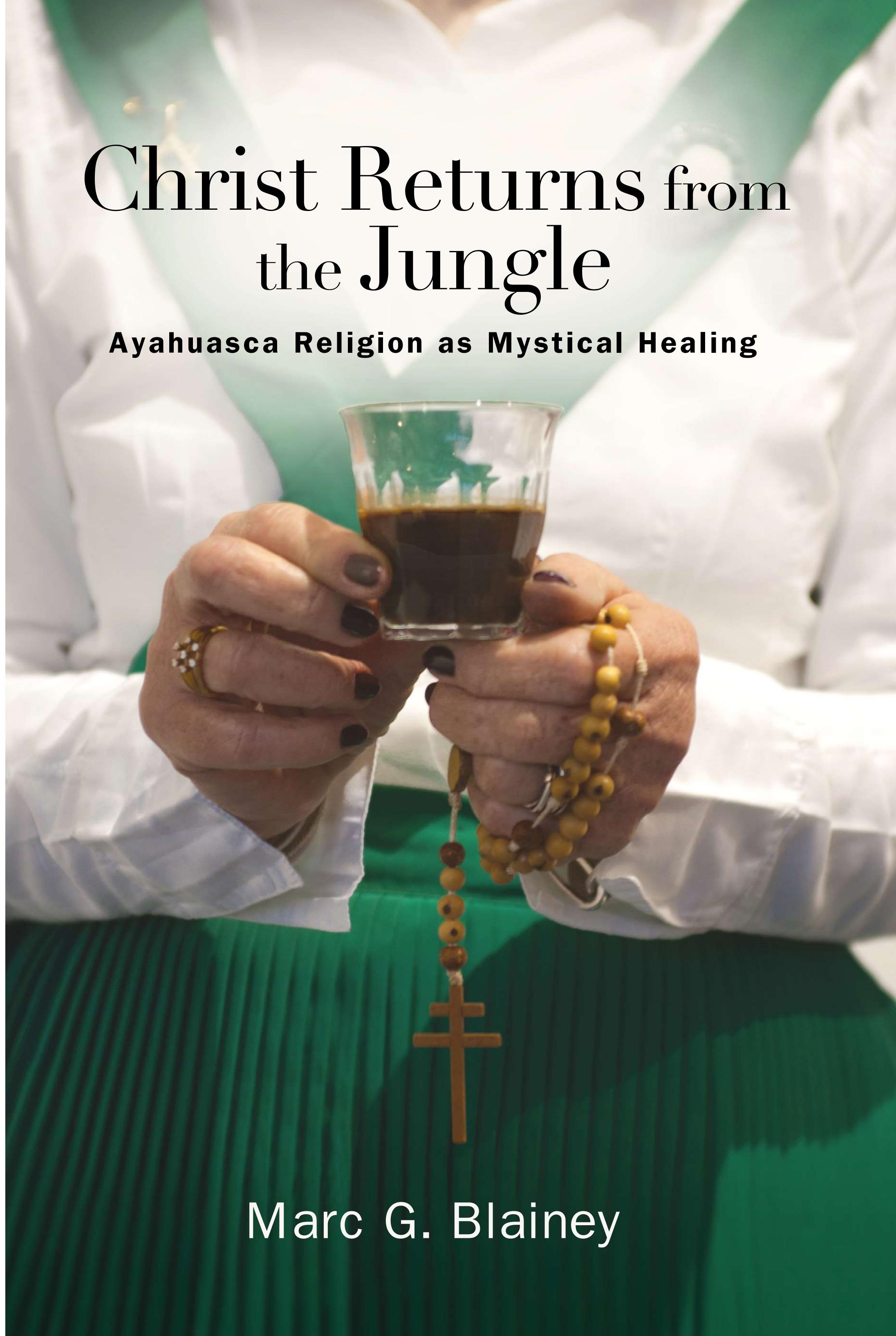

What follows are excerpts from the book Christ Returns from the Jungle: Ayahuasca Religion as Mystical Healing (2021), published by State University of New York (SUNY) Press, now available in hardcover and paperback at online booksellers or directly from the publisher here.

Amid instrumental music to accompany the singing of scripture–like hymns, ayahuasca is ingested as a holy sacrament in Santo Daime rituals (dubbed “works” or trabalhos in Portuguese), much like the wine distributed at a Catholic mass.

Through 14 months of fieldwork, between 2009 and 2011, I gathered ethnographic data concerning European expansions of Santo Daime (pronounced Sahn–toh Die–mee), a Brazil‑based religion whose devotees drink the mind–altering beverage ayahuasca, which they reverently christen with the label “Daime.” This bitter, brown fluid—a technological innovation first discovered by, and thus, rightfully, the intellectual property of Indigenous communities in Amazonia—has a powerful capacity for modifying human consciousness because it contains N,N‑Dimethyltryptamine (DMT). Amid instrumental music to accompany the singing of scripture–like hymns, ayahuasca is ingested as a holy sacrament in Santo Daime rituals (dubbed “works” or trabalhos in Portuguese), much like the wine distributed at a Catholic mass.

Presently, with notable exceptions, such as Brazil, Spain, the USA, and Canada, most governments presume the practice of Santo Daime to be a criminal act because the United Nations designates DMT as a dangerous and illicit “hallucinogen” (see Anderson et al., 2012; Tupper & Labate, 2012). The recent arrival of this unconventional spirituality therefore represents an ethical dilemma for the “Free World”: How can liberalist values of religious freedom be sustained if the fundamental component of Santo Daime religious practice is not permitted? Anthropology, the discipline that strives to account for cultural variation, is tailor–made to intercede in such cosmopolitical debates about stigmatized populations because anthropology’s core analytical specialty is clarifying otherwise obscure social phenomena.

Why are some Europeans, raised within a social milieu dominated by secularism and mainstream Christianity, now choosing to adopt Santo Daime spiritual practices?

This book’s “ethno–phenomenological” lens includes explication of 102 semi–structured interviews recorded with Santo Daime adherents (a.k.a. “daimistas”), informants hailing from 16 different European countries. In presenting the results of intensive participant–observation at Santo Daime ceremonies in Europe, this volume offers empirical and empathic answers to the research question: Why are some Europeans, raised within a social milieu dominated by secularism and mainstream Christianity, now choosing to adopt Santo Daime spiritual practices?

exist indicated by a double-armed cross (following the precedent set in Labate and

Araújo [2004, 614; with Sandra Goulart]); black boxes indicate countries whose

citizens attend Daime works in Amsterdam.

Upon my initial arrival for fieldwork in Belgium, a veteran daimista named Luk[i] served as one of my key informants. At 55 years of age, Luk was then an unmarried landscaper living in rural Flanders. Invoking “the established Brazilian narrative of cultural confluence” (Dawson, 2013, p. 89), he explained to me why he thinks some Europeans are attracted to the Santo Daime religion, which was founded in 1930 by an Afro–Brazilian rubber tapper known as Mestre Irineu:

People are searching for something that puts them on a higher level. People want to be conscious in their life, I think. They’re searching for that. Not to be put asleep all the time, by consumption and by watching television and going to sports …

So, when you find something that appeals to your deepest self, you want to know more about it. And I think there the Santo Daime has a big role to fill. But the Santo Daime’s not for everybody. It doesn’t have the ambition…

It’s a doctrine; it’s a school where you can learn to deal with your own life, with the mysteries of life. It gives answers to those very profound questions: What is the meaning of life? I don’t know! [laughs heartily]. But it gives you a direction. That’s also why it works, for example, for drug addicts, or ex‑drug addicts; they see a new direction in their life, and so they can overcome their addiction.

And, we have the addiction to materialism; we want a new car. All our culture is about having things. And with the Santo Daime, you see you don’t need that anymore… You don’t have this enormous hole anymore in your soul, that stays empty, that the shopping center can’t fill…

Me, myself, I consider Mestre Irineu as a prophet, someone who brings a holy message from the Divine. Also, he brought this doctrine. He was the in‑between between the [South American] Indians and the Western civilization. He translated the ayahuasca into Daime. He was Brazilian but he was a Black man. He was like a synthesis between Indian, African, and European. Between red, black, and white … Some people in the Daime they say it’s like you had Jesus, and he gave his lessons, and then, Mestre Irineu renewed those lessons. He planted this holy doctrine again in the world a second time. The second arm of the cross. You must find that out yourself, everybody’s different.

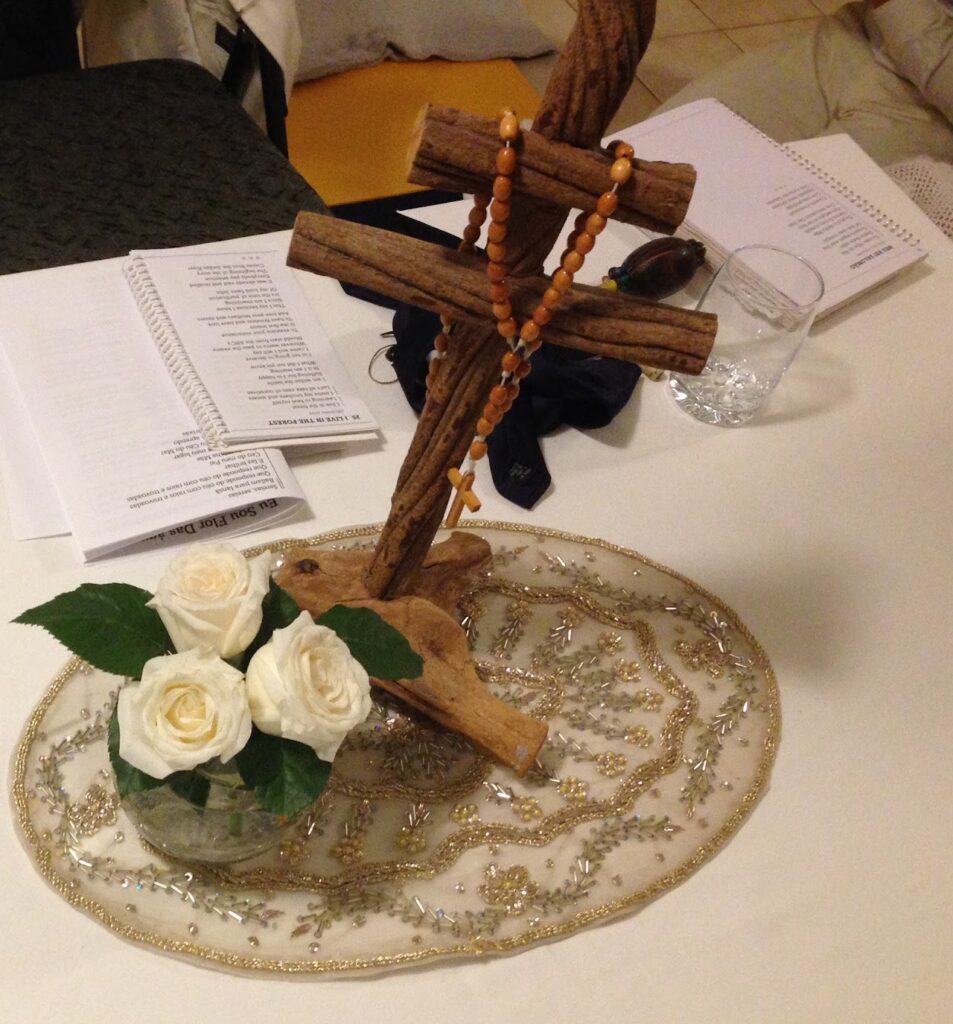

Accordingly, this book carefully unpacks the belief of daimistas around the world that the double–armed ☨ Cross of Caravaca, one of the main symbols of Santo Daime, represents the return of Christ. Daimistas interpret this, not as Jesus revisiting Earth as an individual, but rather that the liquid Daime brew is itself a “key” to parousia (the “Second Coming”) with which access to the spirit of “Christ Consciousness” can be fostered inside each person who partakes of this ayahuasca religion (Polari de Alverga, 1999). This is highlighted when some daimistas fashion Caravaca crosses from the Banisteriopsis caapi vine that is used to make ayahuasca, implying that, by drinking the Daime beverage, one takes the wood of Jesus’s cross into one’s body.

The Santo Daime is a “perennialist” form of Christianity that deems Christ’s teachings as complementary and harmonious with Indigenous spirituality and the mystical ideas of other religions. Above, Luk conveys daimistas’ conviction that Mestre Irineu’s “doctrine” is a “synthesis” of universal truths applying to all humans regardless of cultural upbringing. Through disciplined drinking of the Daime potion—itself a synthesis of distinct phytochemical ingredients into a homogeneous solution—daimistas believe they can transcend superficial divisions between different wisdom traditions, making contact with the perennial source of all spiritualities.

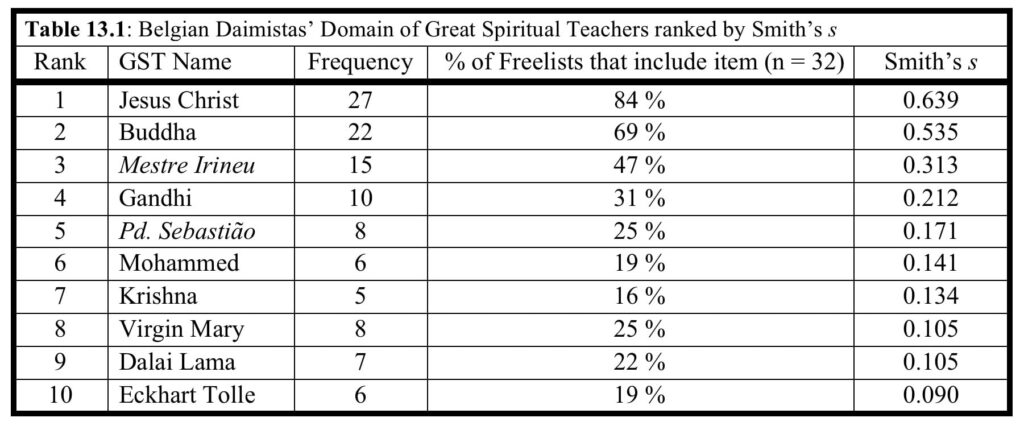

In order to get a more precise sense of European daimistas’ shared values of mystical perennialism, I administered a “freelisting” exercise (see Borgatti, 1994), asking daimistas to itemize all the people that they esteem as Great Spiritual Teachers. As seen in this Table from Chapter 13[ii], the names mentioned by my core sample of 32 daimistas from Belgium (16 males, 16 females) span a wide array of spiritual traditions from different historical eras:

With regard to emotional and spiritual healing functions of Santo Daime, every daimista I met expressed their belief that most sicknesses of body and mind are communications from one’s true spiritual (or “Higher”) self. In accepting that some terminal illnesses are incurable because of divine will, Daime logic holds that the majority of psychophysical maladies serve a “signal” function of drawing attention to unaddressed sicknesses or wounds of one’s spirit; in the context of European centers, daimistas prefer to view corporeal and mental suffering as symptoms caused by one’s egotistical refusal “to surrender to the voice of God” (Schmidt, 2007, p. 177; see also, Barnard, 2022). Hence, their theories about how Daime stimulates worldly wellness by resolving dissonances of the internal psyche concur with existentialists such as Kierkegaard (1989 [1849], pp. 50–51), for whom a “sickness of the soul” is rooted in “the torment of contradiction in despair.”

There is no better source than the Dutch Daime leader Geraldine Fijneman[iii] (1945–2016), the late “Madrinha (Godmother) of Europe,” to communicate common themes in my informants’ ideas about sickness and health of the egoic self:

The Daime is giving you advice… First thing: you have to clean… otherwise you cannot receive the knowledge because you’re blinded by your own ego… The goal is that the ego is not interrupting anymore, because you need a healthy form of ego to create. The sick ego is to put yourself in front in a way that keeps you [from] your goal. In the hymns we say, Mestre na frente [Master in the front], not the ego… Mestre is what we follow… the Mestre is Jesus…

The ego has many forms, many expressions… It is very easy to say, “What an ego that person has!” Many times, ego is behind [it] when you look very sad, you need a lot of attention because you’re complaining, that’s also ego… [The Daime] cleans all these layers of conditioning that has to do with the ego,… from your parents, from the influence from outside,… a lot of times, you are doing what they expect from you, you don’t even think, “Do I really want that?”

When you are born [and] you grow up, you have to form your ego (otherwise you cannot create), and after that, the ego becomes so ill because of all kinds of [external] influences, that you have to drop the ego again… I think a sick ego is very dangerous (you can hurt yourself and others a lot with it), but [with] the healthy ego you can create beautiful things… [A healthy ego] realizes the traps, that it is not yourself who is doing that fantastic thing, but it is God who works through you… we are inspired…

You have to open yourself up for that and to allow it, and then you need to work on your ego… because the ego is always proud that he’s doing it… Most illnesses are coming out of this: the wrong understanding.

daimistas look to Daime rituals to help them diminish the “sick” aspects of their ego in favor of cultivating a “healthy ego,” whereby the spiritual “Higher Self” is liberated from corrupt preoccupations of the “lower self.”

As exemplified in this interview with Madrinha Geraldine, daimistas look to Daime rituals to help them diminish the “sick” aspects of their ego in favor of cultivating a “healthy ego,” whereby the spiritual “Higher Self” is liberated from corrupt preoccupations of the “lower self.” As is demonstrated throughout this book, daimistas seek to overcome diseases by viewing their suffering both inside and outside Daime rituals as a constructive process that guides them toward choosing faith in a multicultural Godhead over the temptation to egotistical despair.

Most, but not all, of my informants are deeply suspicious of institutionalized Christianity in Europe. Many dislike what they see as a history of Jesus’s model of peace and charity being perverted for the purposes of imperialist and commercial powers. Daimistas believe their hymns prophesize that Daime can “bring good remedies” by reinstalling Jesus’s original message (see Mestre Irineu’s hymn #75). In other words, daimistas testify that Daime coaches them how to be better Europeans—less Eurocentric, more xenophilic—by showing them they have much to learn from foreign ways of being and knowing.

Daimistas herald Daime as a newly reformed Christianity, whereby each individual devotee seeks to decolonize their own mind by stripping themselves of their Eurocentric/egocentric attachments. Yes, there no doubt remain valid, important, and pervasive concerns about “eurochristian” appropriations or “erasure” of Indigenous entheogenic traditions in the Americas (see Green, 2020). Conversely, my fieldwork suggests that daimistas are themselves facing persecution from European governments not because they are Christian, but because they adopt the taboo behavior of altering their consciousness with botanical medicines from the “New World.”

For European daimistas, Santo Daime is actually a means for curing sicknesses of arrogant egocentrism and ethnocentrism at the heart of the Western project.

If anything, the faith healing theology of Santo Daime represents the strategic appropriation of Christianity by Afro–Brazilian and Indigenous ayahuasca traditions. For European daimistas, Santo Daime is actually a means for curing sicknesses of arrogant egocentrism and ethnocentrism at the heart of the Western project. Unlike the history of chauvinistic violence perpetrated through European invasions across the non–Western world, daimistas are engaged in a critical self–reflection housed within a moral system of compassion for all people and responsibility for the whole Earth. For them, the chalice of Christ now arriving from the Amazon jungle has been purified of colonialist pollutions, an antidote to egotistical despair, returning to Europe through the Daime liquid and Mestre Irineu’s teachings.

Art by Fernanda Cervantes.

References

Anderson, B., Labate, B. C., Meyer, M., Tupper, K. Barbosa, P., Grob, C., Dawson, A., & McKenna, D. (2012). Statement on ayahuasca. International Journal of Drug Policy, 23(3), 173–75.

Barnard, G. W. (2022). Liquid Light: Ayahuasca visions and embodying divinity in the Santo Daime religious tradition. Columbia University Press

Borgatti, S. (1994). Cultural domain analysis. Journal of Quantitative Anthropology, 4, 261–78.

Dawson, A. (2013). Santo Daime: A New World religion. Bloomsbury.

Green, R. K. 2020. Ayahuasca’s religious diaspora in the wake of the Doctrine of Discovery (Doctoral dissertation). University of Denver.

Green, R. K. (2021, April 12). On decolonizing and psychedelics. Chacruna.net. https://chacruna.net/decolonizing_policy_psychedelics/

Kierkegaard, S. (1989[1849]). the sickness unto death: A Christian psychological exposition for edification and awakening. Penguin Books.

Labate, B. C., & Araújo, W. S. (2004). O Uso Ritual da Ayahuasca [The ritual use of ayahuasca] (2nd edition). Mercado de Letras.

Polari de Alverga, A. (1999). Forest ofvVisions: Ayahuasca, amazonian spirituality, and the Santo Daime tradition. (Workman, R. Trans). Park Street Press.

Schmidt, T. K. 2007. Morality as practice: The Santo Daime, an eco‑religious movement in the Amazonian Rainforest. Uppsala Universitet. Tupper, K. W., & Labate, B. C. (2012). Plants, psychoactive substances, and the International Narcotics Control Board: The control of nature and the nature of control. Human Rights and Drugs, 2(1), 17–28

[i]. Luk passed from this life in 2017 at age 61, and so I use his real name here. In the book I called him Lars; and, likewise, all living informants in the book are given pseudonyms to protect their identity (any resemblance to the names of real people is coincidental).

[ii]. There is a small typo in the book for Table 13.1, which should correctly state that n = 32 (n = 42 applies to Table 13.2 data for all non-Belgian informants).

[iii]. As another exception to pseudonyms, I publish Madrinha Geraldine’s true name here, both because of her status as a public figure in the global daimista community and for posterity, since she passed away in 2016 at the age of 71.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?