“turn on, tune in, drop out” provoked a conservative backlash of such ferocity that our society is still reeling from it

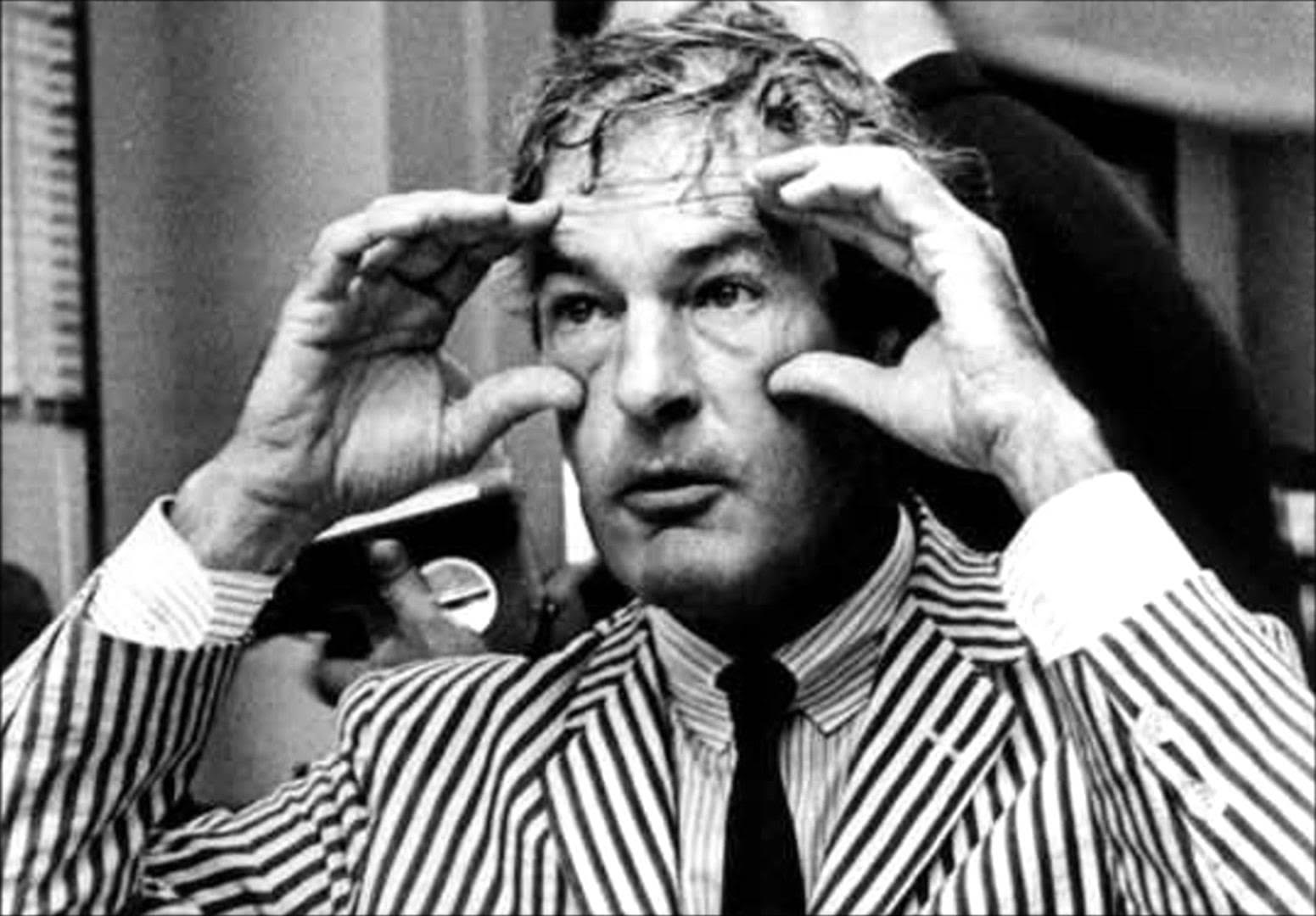

As the Western world approaches the dawning of a psychedelic renaissance, it would be wise to pause for a look back at our history, if we hope to avoid the doom of repeating it. While it’s not fair to hold Timothy Leary wholly accountable for the reaction that the psychedelic movement of the 1960s elicited from the dominant culture of its time—he was, in the final analysis, more the movement’s lightning rod than its architect—we cannot overlook the outcome of his attempt to lead a full-frontal assault on the existing power structure, which was frankly disastrous. His rallying cry urging Americans to “turn on, tune in, drop out” provoked a conservative backlash of such ferocity that our society is still reeling from it: Nixon famously identified Leary as “the most dangerous man in America,” declared the War on Drugs, and enacted the prohibition of psychedelics via the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. Just like that, the most powerful tools for psychotherapeutic healing and consciousness exploration known to humankind were driven out of public reach into the underground, where they have remained, by and large, for almost half a century.

Yet, for all that, the most valuable treasure to spill out of the Pandora’s box of 1960s counterculture was not lost. Many people were permanently and fundamentally transformed by the encounter with sacred and transcendent dimensions of human experience afforded to them by these substances. They did not lose sight of the importance of preserving, for their fellow beings, the possibility of this encounter, the capacity for this kind of transformation. Instead of ceding defeat, they chose to learn from the movement’s failures, to forge different paths through a landscape grown so much more foreboding than before; slowly, doggedly back to the promise of a society that permits the exploration of personal divinity through these uniquely powerful means.

One of these people is Rick Doblin, who, three decades after founding MAPS at the height of the Reagan administration and “Just say no”hysteria, has led the efforts of a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens to the cusp of something truly incredible: restoring the legitimacy of psychedelics in the eyes of the dominant culture, by demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of their use in a medical context. He did so by recognizing that long-lasting societal change of this magnitude cannot be imposed from without, as Leary sought to do; it can only be accomplished from within. He educated himself on the slow, stodgy channels of public policy change extant within the labyrinths of entrenched power, and, against all odds, found a way to successfully navigate them.

As a psychiatrist and clinical researcher who has seen and experienced the profound healing potential of these substances, I am deeply indebted to Rick and to MAPS for these efforts. They have provided me with tools to achieve not the mere abatement of symptoms—which is the best that traditional psychiatric medications can hope to accomplish, when they work at all—but to effect true healing. It is hard to overstate the magnitude of the unmet need for effective treatments in the field of mental health care: suicide rates in the U.S. are currently the highest they have been in 30 years, and there are hundreds of millions of people suffering from deadly illnesses like major depression, drug and alcohol addiction, and PTSD, for whom conventional treatments have proven completely ineffective.

While it is by no means a panacea, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for these conditions, even in cases previously considered intractable, has shown incredible effectiveness, approaching in many cases that of a cure. I have seen this with my own eyes, through my work with both psilocybin and MDMA. And herein lies the real tragedy, because it is hard to imagine where the field of psychiatry would be right now, had the psychedelic research that began to blossom in the 1950s not been truncated by the end of the 1960s; had Leary, in other words, adopted an approach subtler than storming into the lion’s den and poking the biggest cats he could find in the eye. How many lives ravaged by suicide, addiction, and violence could have been saved? How much suffering alleviated, or prevented?

This lost opportunity is a flood of tears, to be sure, but it is water under the bridge all the same. Our task now is to move forward, and try to help the many millions of people who can still be helped. Surmounting the considerable hurdle of decriminalization and FDA approval is just the first step. Our real task lies further ahead, and it is formidable. To address a public health need of this magnitude requires an enormous infrastructure, which will cost hundreds of millions of dollars to implement. The reality is that it is well beyond the means of a non-profit organization like MAPS, reliant on charitable donations for its daily operations, to establish this kind of infrastructure, let alone operate it sustainably.

The reality is that, outside of a tax-funded government agency—an unlikely champion of psychedelic use, to say the least—a for-profit company is the only kind of organization capable of operating on this scale. In other words, for an organization to be capable of reliably delivering a high-quality, complex service such as psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy to many thousands of people over the course of many years, it must be capable of sustainably generating enough of its own revenue to provide for the training and salaries of hundreds of providers and support staff, maintenance of facilities, acquisition and storage of medicine, and so on. Charitable donations simply aren’t going to cut it.

In the case of MPBC, 100% of its profits are committed to its chosen public benefit, namely the furtherance of psychedelic research

This is, in fact why, in anticipation of conducting the Phase 3 clinical trials that will hopefully result in FDA approval for MDMA-assisted therapy, MAPS established its wholly-owned subsidiary, the MAPS Public Benefit Corporation, or MPBC. To be clear, a public benefit corporation is defined as a for-profit company whose establishing charter formally commits a substantial portion of the revenue it generates toward a specific public benefit. In the case of MPBC, 100% of its profits are committed to its chosen public benefit, namely the furtherance of psychedelic research. More recently, another for-profit corporation called COMPASS Pathways has entered the psychedelic arena, and is gearing up to conduct Phase 3 clinical trials, seeking approval from the FDA and its European equivalent, the EMA, for psilocybin-assisted therapy for treatment-resistant depression.

These developments, particularly the entry of COMPASS into the field, have generated a lot of controversy in the psychedelic community; this was a hot-button issue at the conference Cultural and Political Perspectives in Psychedelic Science, recently held in San Francisco. Some have argued that for-profit companies are structured to place the private interests of their shareholders above those of the public and as such, are inherently corrupt; hence their involvement in this work can only result in the down fall of the psychedelic movement. Now, I am certainly not here to deny the existence of corrupt and unethical business practices, still less to defend them, nor amI here to sing the praises of capitalism; I am aware of the ways in which it fosters inequality and injustice, encourages the exploitation of natural and human resources, and concentrates power in the hands of a privileged minority. I am as fervently opposed to these tendencies as much as anyone with a healthy conscience ought to be.

But I must also live in the real world, as we all do, and operate within the limitations of reality as it is presented to me, even as I seek to improve the conditions giving rise to those limitations. And the reality we all live in is that, unless you’ve decided to live completely off the grid, grow your own food, weave your own fabric, smelt your own metal, and so on—in which case, kudos to you, but how are you even reading this article?—then you regularly rely on for-profit companies for at least some of the goods and services required to sustain life in the modern world. Until we can find a better way, these are the only means by which private citizens can get things done on a large scale. Furthermore, the presupposition that a company cannot be run both ethically and profitably is frankly untrue; to insist otherwise precludes a rational discourse on the subject at hand.

More to the point, our present-day reality is that, outside of the very small number of people exposed to the therapeutic use of psychedelics in clinical trials, anyone likely to put themselves in a position to have a powerfully transformative psychedelic experience is, in one way or another, already on the fringes of society. This is the effect of the criminalization of these substances, and these will continue to be the prevailing conditions until psychedelics are decriminalized and made available to the mainstream for widespread use, in a manner that is readily accessible, safe, and therapeutic.

And here is the real crux of the issue, and the question I have for those who oppose the mainstreaming of psychedelics and the establishment of the revenue-generating infrastructure that this will inevitably require: what is your alternative? How else do you propose to deliver this treatment in a manner that is safe, reliable, and affordable to the millions of people in need of it?

To me, opposing the entry of for-profit organizations into the psychedelic landscape is to be in favor of perpetually restricting access to psychedelics for all but a tiny fraction of the population using them in marginalized or underground contexts. This is a position I find ethically unacceptable.

I will concede that the decision made by COMPASS to ignore the example set by MPBC and refuse to sign The Statement on Open Science is troubling. I would also argue that too much is being made of it. A full examination of the facts supporting this argument is outside the scope of this essay; suffice it to say that all important aspects of the technique used in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, not to mention the psychedelic molecules themselves, are already in the public domain. Furthermore, the need for this treatment is unfortunately so vast that no single organization, no matter how well-funded, could possibly crowd out its competition.

To my mind, the growth of a for-profit industry around the delivery of psychedelic-assisted therapy is not the cause for fear and lamentation that some have made it out to be

To my mind, the growth of a for-profit industry around the delivery of psychedelic-assisted therapy is not the cause for fear and lamentation that some have made it out to be. Rather, it is a marker of the tremendous success the psychedelic movement has had in restoring legitimacy to the use of these extraordinary tools for healing and the exploration of human potential, and represents the solid ground this movement must have underneath it to have any hope of creating the changes this world so desperately needs.

Note: A response to this article has been published here

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?