- How Indigenous & Black People are Fighting Colonialism in the Academy - September 2, 2020

- How Feminine is Ayahuasca? - November 21, 2016

- How Indigenous & Black People are Fighting Colonialism in the Academy - September 2, 2020

I came to theory because I was hurting— the pain within me was so intense that I could not go on living. I came to theory desperate, wanting to comprehend— to grasp what was happening around and within me. Most importantly, I wanted to make the hurt go away. I saw in theory then a location for healing.

bell hooks, Theory as Liberatory Practice (1994)

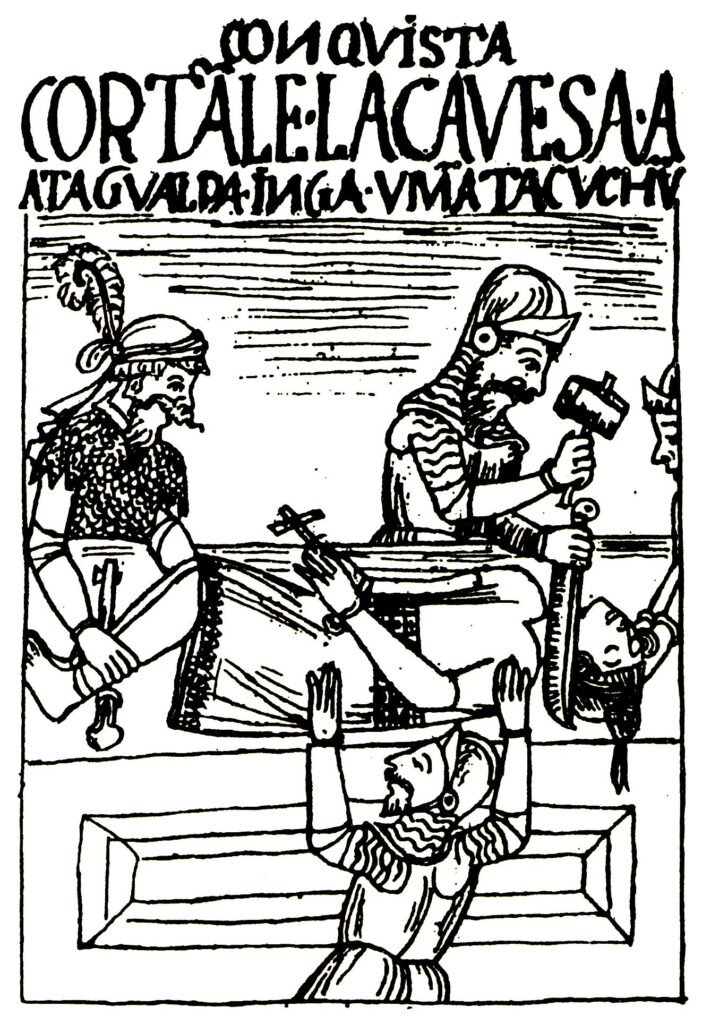

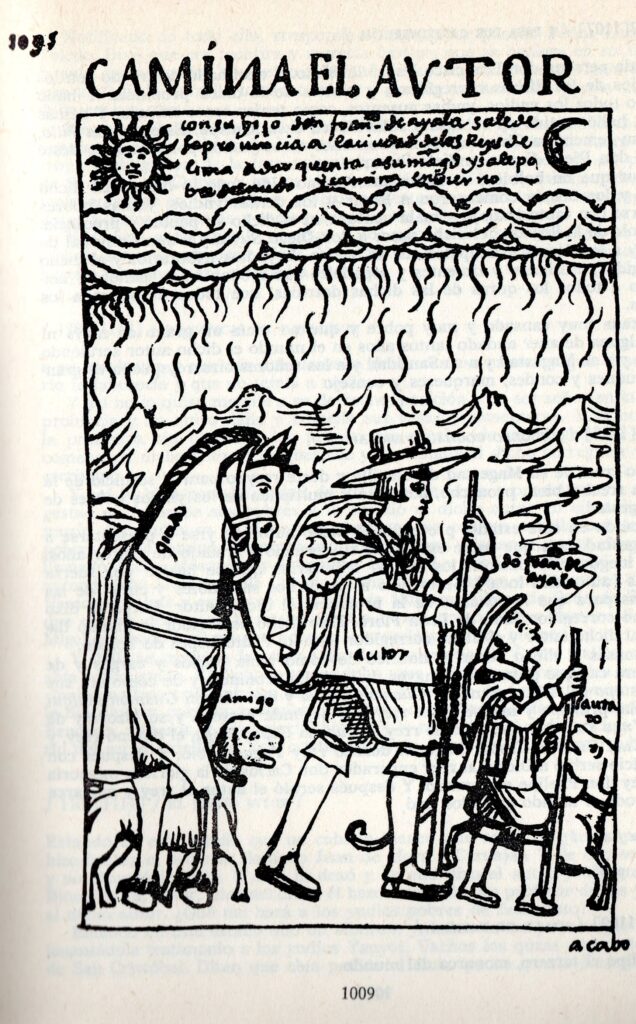

Decolonization: Heroes Must Fall

#RhodesMustFall, the protest movement started by university students in 2015 in Cape Town, brought the word “decolonization” from Africa to the world. The process did not have to do only with the removal of the statue of colonizer Cecil Rhodes from the campus of Cape Town university, but also with the public revolt against the many senses that colonization imprints in the bodies and subjectivities of South African Black students (Efron, 2018). During and after the removal, performances took place showing how people’s bodies connect to material culture through systems of symbols and experiences where things and people share the precious substance of identity and ancestrality. Some years later, massive protests reemerged. In may 2020, during the beginning of the huge global COVID-19 crisis, the #BlackLivesMatter movement was triggered by George Floyd being murdered by a White Supremacist police officer in North Carolina.

Colonization is one of the pervasive aspects of Western Modernity. In the context of COVID-19, it became evident that structural racism and the genocide of Black and Indigenous people is a fact that remains as an open wound in Latin America. The conquest of the Americas submitted the bodies, knowledge, and experiences of Black and Indigenous people through a constant genocide, ecocide, and epistemicide that included a permanent strategy of biological, economic, cultural, linguistic, and religious wars. There is a term that corresponds to genocide in the world of ideas, texts, and theories: its name is “epistemicide.” In particular, epistemicide (Carneiro, 2016) was perpetuated through a canonical vision of modern science passed through the Enlightenment in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries, making invisible the ancestral wisdom of the Abya Yala people who lived and flourished in the old land of the so-called “Americas.”

It is interesting to note that the process of decolonization does not affect only people from the Global South. In November 2018, the French Journal Le Point posted an intriguing news: Eighty renowned national intellectuals denounced decolonization as a strategy for “racism” launched by some African, Asian and Latin-American intellectuals living in France who held a decolonial or post-colonial perspective. Reading this manifesto, we can perceive how deep the silence is of the canonic truths, maintained by Whiteness, structural racism, and xenophobia. Intellectuals such as Gloria Anzaldúa, Frantz Fanon, Achille Mbembe, David Mwambari, Vandana Shiva, Maria Lugones, Chimamanda Adichie, and Arturo Escobar were (and are) resistant voices dismantling the oppressive, Eurocentric logic at the centers of knowledge production in the world. Those “skilled migrants” emerged in the decolonial scenarios by recognizing themselves as being a part of an intellectual diaspora who did not want to mimic the colonizer, but rather to confront him by writing and questioning the Eurocentric canon and its effects.

What is the South-South Dialogue?

The lack of interest in communities and countries that go, and went, through similar experiences does not seem to be a characteristic exclusive to Brazil, though. People and communities in the Global South do have a huge difficulty identifying with each other. We were thought to identify with our dominators, as Frantz Fanon (1952) comprehensively analyzed. We do not read each other; we do not quote each other. We can hardly get inspired by each other’s ideas; we have a huge difficulty in understanding our structural position in the geo-localized Global South.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, after an intense political struggle in the public arena, our Indigenous and quilombola [Afro-descendant] and Black students finally got to study in the university through affirmative actions; their bodies were allowed in the universities and other spaces for superior education. But there was no space to bring together their knowledge, their experiences, or their perspectives on the world. They are longing to be able to quote their ancestors and their daily struggles as a valid source of knowledge production.

Brazil has the smallest number of black professors, and even fewer Indigenous professors. As academics, with White-looking people teaching our classes in Brazilian universities, we spend our lives trying to understand what it would be to think with a “White head” and to live with a White body in a White world. We perpetuate White Supremacy by not even being conscious of our racism. And our racism is not a “morally dirty choice”; it is in the fact that we accept the way our institutions and politics of knowledge are operating. As Angela Davis (1983) stated, if it is not anti-racist, our location is plainly racist—and it is because racism is structural to our societies, “it is there” by default.

There are Black women speaking from the margins; anthropologists that, in face of the lack of Black anthropological authors from the beginning of the century, are quoting Black authors from literature.

Despite this strong tendency to internal colonialism, some people are doing a vigorous job. They found the term “decolonize” to speak about this discomfort. Others preferred the idea of “countercolonization” (Santos, 2015). They said “epistemic justice” is necessary. There are Black women speaking from the margins; anthropologists that, in face of the lack of Black anthropological authors from the beginning of the century, are quoting Black authors from literature. They are bringing the Black, female body´s experience—like the trash collector from Rio de Janeiro, Carolina Maria de Jesus (1963)—to the core of the production of knowledge. Indigenous people, since they started to meet up with each other and to find a common political identity, despite the huge apparent cultural differences, embraced the idea that being an Indigenous person in Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Panama or Chile involved similar experiences and resulted in the same struggle, despite the domain of different national frontiers.

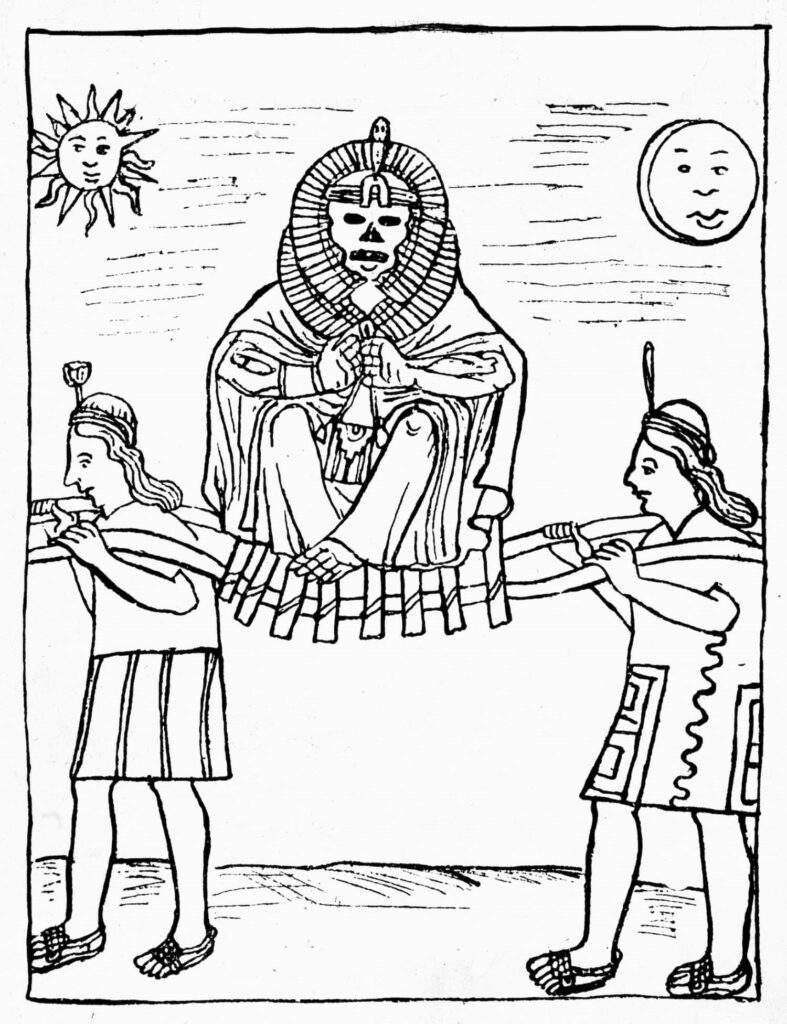

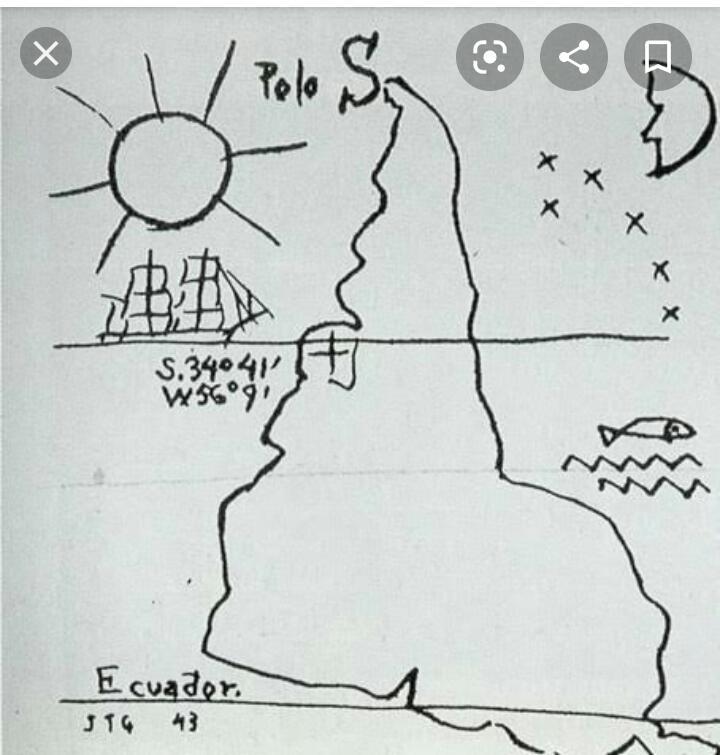

Calling Places for What they Are: Abya Yala, Our Continent

Numerous Indigenous people from Portuguese and Spanish-speaking countries choose to recognize themselves under the Abya Yala unity. This idea has also spread to areas outside of Latin America. Choosing this word acceded to a very poetic hand of fate. In the year of 1975, and after an Annual General Meeting at Chilliwack, British Columbia, Canada, Takir Mamani, an Aymara leader from the Túpac Katari movement, stopped to visit his peers from the Indigenous Kuna (or Guna) community in the territory of what today is called Panama. They were just celebrating the victory of the defense of their territories against Thomas Moody, a businessperson from the United States who had started an aggressive tourist company in their territories some years before.

The old name Abya Yala means “an eternal flowering land” and is a part of the Kuna cosmology. Takir Mamani was told then to spread the word in the rest of the Americas.

Takir Mamani heard the old leaders speaking about re-vindicating not only their physical territories, but also the names given to them. And the Kuna, like many other Indigenous people, are certain about that you cannot inhabit a land with dignity if you don’t give it a dignified name. The old name Abya Yala means “an eternal flowering land” and is a part of the Kuna cosmology. Takir Mamani was told then to spread the word in the rest of the Americas. That is why the indigenous name Abya Yala is being increasingly used by the Indigenous movement from Brazil and the rest of Latin America, and why, slowly, Indigenous academics and other academics who are fighting together for a fairer world are adopting it.

In order to broaden the perspective of Abya Yala in the circuit of the dialogue of knowledge and bodily experiences, we can propose an Abya-Yala Sciences and Wisdoms Network, encouraging not only a dialogue of knowledges, but of beings, feelings, affections, and life experiences, so that the wisdoms that have been historically excluded from the academies start to enter into a side-to-side dialogue with all the fields of science in equal conditions (Arias, 2010). Those views not only offer information, but the possibility to start knitting old and new civilizing horizons.

The heresy of allowing a plant, and even a psychoactive plant such as ayahuasca, to be a companion for life, or even a teacher, as the Brazilian educator Maria Betania Albuquerque (2009) states, is something that the canon cannot accept without embracing the fear of breaking into pieces.

The heresy of allowing a plant, and even a psychoactive plant such as ayahuasca, to be a companion for life, or even a teacher, as the Brazilian educator Maria Betania Albuquerque (2009) states, is something that the canon cannot accept without embracing the fear of breaking into pieces. And that is what Indigenous, mestizo, and urban cultures linked to ayahuasca are proposing: decentering the logos and bringing ancient wisdom to the core of their actions. It is important that we note this is not only a “sophisticated intellectual trip”: the struggle to make knowledge in universities less logocentric—and more focused on experiences, senses and the body—is an old topic in the agenda that cultures displaced by illuminism, capitalism, and technocracy are putting forward more urgently with each day that passes.

Decolonization is not about imposing a “New Big Theory” capable of explaining every social action from a universal perspective. It is not even about replacing an old, exclusive, intellectual canon for a new, exclusive, revolutionary canon. It has to do with the possibility of imagining a world where differences are allowed to exist, avoiding the transformation of them into inequalities. The movements against colonialism in our institutions, constitutions, bodies, and minds have not—and certainly should not have—previous recipes, and a fundamental part of this is respecting the diversity and lack of univocity in all the actions of the movement.

In times where the Brazilian president drinks milk in public performances as an eye wink to White Supremacists sharing those symbols all over the world, the actual Bolivian government is burning wiphalas, the rainbow flags representing the dignity of native Andean and, by extension, South American people, as an open provocation. If you are not against racism, you are supporting it. Theorizing is a practice, as bell hooks (1994) states. By exploring plurilingualism and other cultural transits behind the frontiers imposed by nationalism, facing actions of epistemic justice through co-authorship and encounters between ancestral and scientific knowledge, and finally joining the struggles of Indigenous and Black people inside and outside the frontiers of Academia, decolonization became a potent and poetic habit that we joyfully embrace.

Art by Mariom Luna.

References

Arias, P. G. (2010). Corazonar: una antropología comprometida con la vida, miradas otras desde Abya-Yala para la decolonización del poder, del saber y del ser [Corazonar: An anthropology committed to life, other views from Abya-Yala for the decolonization of power, knowledge and being]. Quito: Abya Ayala Editions.

Albuquerque, M. B. (2009). Uma heresia epistemológica: as plantas como sujeitos de saber [An epistemological heresy: plants as subjects of knowledge]. Revista Centro de Estudos Sociais, 328, 1–34.

Carneiro, S. (2005). A Construção do Outro como Não-Ser como fundamento do Ser [The construction of the Other as non-being as the foundation of being] (Doctoral dissertation).University of São Paulo, Brazil.

Davis, A. (1983). Women, race and class. New York City, NY: Vintage Books.

Efron, L. (2018). La colonialidad del saber en la Sudáfrica post apartheid. Movimientos estudiantiles en busca de la transformación/descolonización del sistema universitário [The coloniality of knowledge in post-apartheid South Africa. Student movements in search of the transformation / decolonization of the university system]. In M. I. Cejas (Ed.), Sudáfrica post-apartheid: nación, ciudadanía, movimientos sociales, gobierno, género, sexualidade [Post-apartheid South Africa: nation, citizenship, social movements, government, gender, sexuality] (pp.183–215). Coyoacán, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana – Xochimilco.

Fanon, F. (1952). Peau noire, masques blancs [Black skin, white masks]. Paris: Les Éditions du Seuil.

Jesus, C. M. de. (1963). Quarto de Despejo [Child of the dark]. São Paulo: Edição Popular.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York City, NY: Routledge.

Lugones, M. (2008). Colonialidad y Género: hacia un feminismo descolonial [Coloniality and gender: Towards a decolonial feminism]. In W. D. Mignolo (Ed.), Género y Descolonialidad [Gender and decoloniality] (pp. 13–42). Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Signo.

Mignolo, W. D. (Ed.). (2008). Género y Descolonialidad [Gender and decoloniality]. Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Signo.

Santos, A. B, (2015). Colonização, Quilombos, Modos e Significações [Colonization, quilombos, modes and meanings]. Brasília: INCTI/UnB.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?