Foreigners, and even Brazilians, often feel confused by the fierce accusations leveled by the members of different Brazilian ayahuasca religions against each other. Matters become especially fierce in the case of attacks, often seeming to verge on a desire to ban the brew entirely, made against members of CEFLURIS or ICEFLU, followers of the late Santo Daime leader Padrinho Sebastião. This is allegedly due to their acceptance of the sacramental use, in certain of their rituals, of cannabis with ayahuasca. Another point of discord is their acceptance of possession trances alongside the shamanic flight more common among indigenous ayahuasca users. However, if one looks a little further into the history of Amazonian Indian and mestizo shamanism, one will find many different plant species being used in conjunction with ayahuasca; some of them with considerable psychoactive properties. Similarly, in Rio Branco, one will find followers of the Barquinha religion who reserve a special place in their rituals for mediumship and for possession trances and do not receive the criticisms leveled at CEFLURIS or ICEFLU.

For decades, the Brazilian ayahuasca religions have been vying with each other in their attempts to prove which is most “respectable.” Behind these efforts, one cannot help but perceive a certain unease at the fact that in all their different rituals, they all use a powerful psychoactive substance containing, among other ingredients, DMT, which is generally considered to be a “dangerous drug” by pharmacologists and doctors. After all, one must remember that, although the list of proscribed plants drawn up by the Brazilian Ministry of Health includes coca, poppies, peyote, and cannabis, it does not, at the moment, include the species used by the religious groups to make ayahuasca; another section of the list includes DMT, an important active principle of the brew, alongside LSD, MDMA, mescaline, and psilocybin. Although originally forgotten due to its then little-known use in Brazil, Banisteriopsis caapi was temporarily placed in the list of banned plants between 1985 and 1986, when the UDV and the Santo Daime started to receive more public attention. These restrictions are to be found in the laws of most countries in one way or another;; they are a reflection of United Nations rulings. In a climate created by strong prohibitionist propaganda, the followers of the ayahuasca religions do not seek to question the basis of the restrictive legislation that they tend to generally approve.. Instead, they restrict themselves to arguing, not very convincingly, that their sacrament “is not a drug.” Despite their efforts, and even after the government issued an official regulation of the religious use of ayahuasca, the sensationalist press to this day insists on referring to these religions as “buzz sects.”

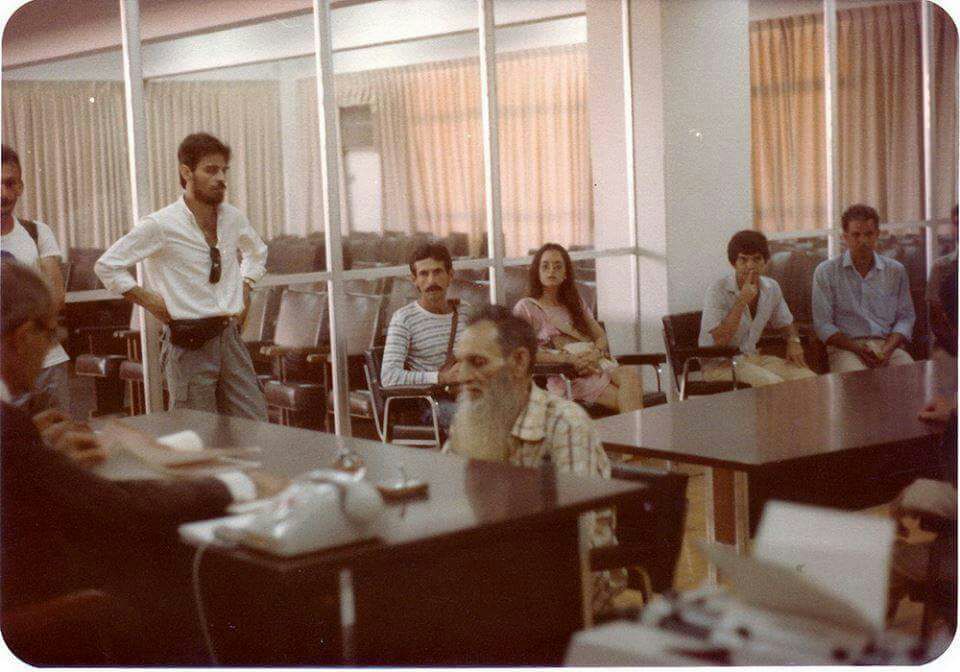

Padrinho Sebastião Mota, spiritual leader of the Colônia Cinco Mil, talking to authorities about the garden of Santa Maria planted at his community. Rio Branco, Acre, Brazil, approximately 1982. Photo by Saulo Petean. Courtesy by Vera Fróes.

Thus, to understand the constant squabbles that frequently interfere in the present political situation, one must go back to the origins of Prohibitionist legislation in Brazil and its wider consequences. The setting is the late nineteenth century, when Brazil had belatedly abolished slavery in 1888 and the monarchy gave way to a supposedly republican regime in 1889, which, in fact, was only an arrangement to guarantee the power of the traditional agrarian elite. The population was then mainly based in the countryside, and was mostly of mixed African or Indigenous descent. This is because, originally, mostly single men, who came over as adventurers, carried out the Portuguese colonization, hoping to become rich and return to Portugal. They brought few women with them and took Indian and African women as their spouses or concubines. Thus, except for the small elite of European descent, most Brazilians were of mixed blood.

After Abolition, the country was faced by a large, newly-released Black population that remained landless and unrepresented in the local politics and was obviously perceived as a threat by the ruling elite. It was also a time when some cities began to develop, and a new urban middle class began to demand its share of political power. The ruling, still mainly agrarian-based White elite sought to model itself on Europe and its scientific developments. The positivist movement led by Auguste Comte in France, and the racist and eugenic notions then widely embraced by scientists all over the world, were thought to light the way to a new civilization. The sons of this middle class, who found one of the few ways to upward mobility in the newly developing medical profession, proposed to “heal” Brazilian society, which they diagnosed as ill and greatly endangered by its strongly mixed African and Indigenous racial composition.

A large campaign was then set forth to turn Brazil into a White country. Massive European immigration was encouraged, and African and Indian cultural elements were condemned as backward and to be eradicated in the name of science and civilization. The newly emerging medical profession was especially set on imposing its monopoly over all healing practices, and traditional folk medicine or spiritual healing was legally condemned as quackery. Traditional African and Indian spiritual and healing practices and rituals that had always been seen with suspicion—but had, in some cases, found tolerance due to the weakness of the local Catholic Church and the lack of trained doctors,—now faced concerted official and legal opposition. The police were often called to break up non-Catholic religious meetings and to imprison healers accused of charlatanism. Indigenous peoples were subjected to even worse treatment, and were largely raped, murdered, and dispossessed of their lands.

Although we can now understand this process in modern sociological terms, one must remember that those living through it had only a common-sense perception of what was happening, and even the more oppressed sectors of society were strongly influenced by the hegemonic values and internalized notions of Black and Indian inferiority. The onset of Prohibitionist measures in Brazil during the early twentieth century was marked by unabashed racist and eugenic discourses aimed at strengthening and developing the “progressive” White sectors and controlling the Black and Indigenous ones. These notions remain strong, and original African and Indian cultural traits only began to receive partial acceptance in Brazil after the ascent of “countercultural” values among the middle class, as a reaction to the excesses of the 1964-1975 military regime. Even to this day, these traits still find strong opposition among the more conservative sections of society, be they rich or poor.

So, during the first six decades of the twentieth century, popular, traditional spiritual cultural practices were thought to be backward and uncivilized, even by the mestizos, Blacks and Indians themselves. To gain respectability with the ruling elite, and even with their prospective followers, their leaders were led to adopt strong European and Christian orientations. So, their need to conform to White standards led them often to avoid possession trances, animal sacrifices, witchcraft, spiritual healing, and “magical beverages,” like ayahuasca and jurema, as well as traditional recreational uses of non-alcoholic psychoactive substances, like cannabis. All these were seen by society in general as being inferior and uncivilized African and Indian cultural traits. Out of their own accord, non-Catholic spiritual leaders and their followers increasingly sought to “whiten” their religious and healing customs, as a means of gaining more social respectability and followers.

These restraints were also imposed on ayahuasca users, although initially their isolated Amazonian contexts led them to go largely unperceived by the national authorities based in distant Rio de Janeiro. Nevertheless, the early leaders of ayahuasca religions, like Mestre Irineu, founder of the Santo Daime, Mestre Daniel of the Barquinha, and Mestre Gabriel of the UDV, were all subjected to police persecution and even suffered periods of imprisonment. It is interesting to note that, originally, “witchcraft” and “quackery” were the most serious accusations leveled against them. It was only after the moral panic around drug use became stronger in the 1970´s that official attention became more focused on the psychoactive brew they used.

Even though openly racist arguments are now considered to be in bad political taste, the Brazilian war on drugs continues to target the Black and Brown populations. Alleging a supposed need to fight drug dealers, the police continue to wreak havoc among the dwellers of the shantytowns and urban ghettoes where most of them live.

The followers of ayahuasca religions in the Amazon have become upwardly mobile in the last decades, and in certain places, like the State of Acre, have gained official support for their religious activities. However, the general unease at the psychoactive nature of their sacrament has reinforced their desire to show themselves as being against drug use to prove their respectability. Thus, the adherence of certain of Padrinho Sebastião´s followers to the spiritual and ritual use of cannabis, which they consider to be as sacred as ayahuasca and which they call Santa Maria, causes indignation among other ayahuasqueros. Unable to accept a common traditional origin for the spiritual and healing use of different plants with psychoactive properties, they insist in differentiating between their own “sacrament” and those they consider to be “drugs.” They accept as natural a distinction that has only developed in the last few decades, when the recreational use of cannabis became a hallmark of the drug use targeted by the Brazilian authorities. So strong and generalized is the adherence to antidrug prejudice that even older divisions among them, such as those arising around other stigmatized traits like possession trances, are forgotten in name of their united campaign against Santa Maria.

Part of their reason for this is that, as stated above, despite official recognition for the religious use of ayahuasca, the brew continues to be seen with great suspicion. This can be seen in the remaining constraints on its production, transport, and distribution, as well as the banning of all uses that do not fit in the rigid definition of “religious,” such as those aimed at medical, artistic or recreational ends.

Given the generally uneasy acceptance of the ayahuasca religions, there remains a constant political threat to their official legitimacy. Changes that might come to privilege more conservative positions in general remain a possibility, as shown by recent developments in Brazilian and world politics. It is possible that they may even come to affect the status of ayahuasca as a “religious sacrament” and not a “drug” in a not-too-distant future.

However, this is a time when anti-Prohibitionist movements are gaining strength in Brazil, as in many other countries, and racist prejudices are under strong criticism. Taking into account that the distinction the ayahuasca religions like to make between ayahuasca and other drugs is not easily shared by the population in general, this seems to be an appropriate moment for them to leave aside ancient rivalries and come together to fight the idea that all psychoactive substances, except alcohol, are to be regarded with suspicion. It becomes increasingly clear that the only way to guarantee the legality of ayahuasca use is to denounce the racist and conservative origins of the existing policies against the use of psychoactive plants in general, including cannabis, the most blatant example of such discretionary prejudices. Only when the shared common sense ceases its focus on banning drug use in general will the ayahuasca religions be able to feel completely at peace, both in Brazil and abroad.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?