- Why Land and Ecology Matter for Global Psychedelics - January 25, 2024

- Coming of Age in the Psychedelic Sixties - March 15, 2022

- Psychedelics, the War on Drugs, and Violence in Latin America - March 10, 2022

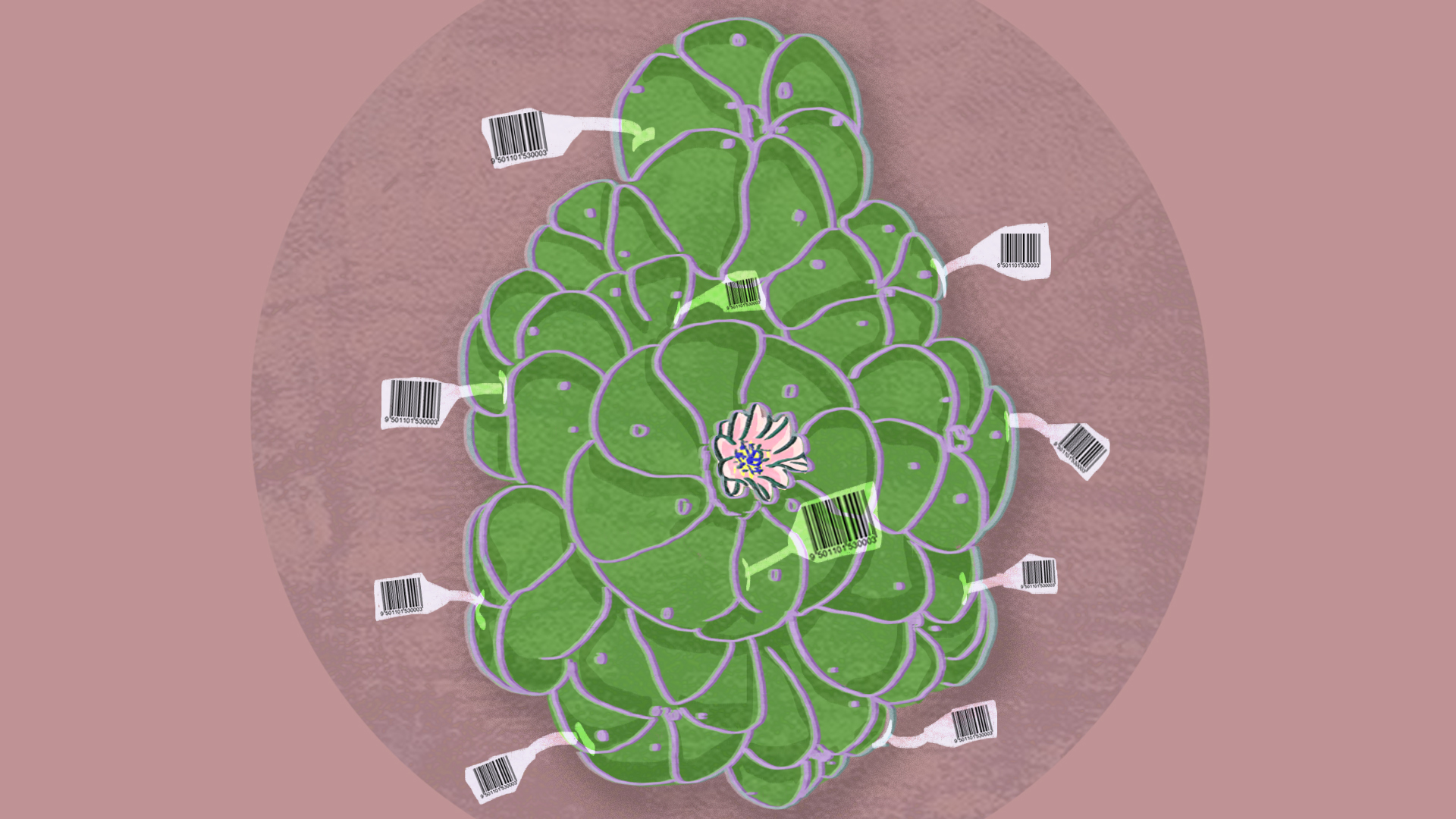

In April, I joined the two-day Psychedelic Liberty Summit, where the voices of several Indigenous participants from Colombia, Brazil, and several tribal nations in the United States discussed their concerns over the parallel trends in decriminalization efforts and the expansion of the use of sacred plant medicines. These medicines and the cultural practices that have sustained their safe and sustainable use are now, more than ever, being consumed by a global public, and many Indigenous peoples argue that these plants and their spiritual practices are being appropriated while their native territories continue to be encroached upon for other global consumption items like minerals, fuel, and beef.

Much of the psychedelic public shudders at the idea of having their practices labeled exploitative, unsustainable, or unethical.

Why these strong words from Indigenous peoples? Much of the psychedelic public shudders at the idea of having their practices labeled exploitative, unsustainable, or unethical. Many are asking why racial and ethnic boundaries are being placed around legitimate versus illegitimate uses of what are called sacred plants, ancestral medicines, or entheogens. Before I continue, I want to note that there exist a great variety of non-Indigenous communities that interact with these medicines outside of the more visible platforms I discuss here. The point of the present critique is to consider the ecological and social vulnerabilities that are ignited by the current surge of interest in these plants as they are marketed and inserted into distinct cultural settings.

The reality both for Indigenous observers and many dedicated to environmental and human rights advocacy is that the global consumption of these plants reflects relations of power rooted in the racial order created with colonialism and the ongoing destruction of the very habitats these plants are endemic to. In other words, seemingly benign practices aimed at therapy or recreation are endangering the very plants they are celebrating.

The Commodification of the Sacred and the Ruin of the Land

For $1200 dollars you can enjoy a two-day “Don Juan Teachings” peyote ceremony organized by a Polish man with the help of a “Huichol shaman” in the comfort of a hotel in Cancún.

“Your authentic peyote ceremony experience will involve true desert camping.” San Miguel de Allende to Real de Catorce, round trip. Price not listed. Bring a sun hat. Tulum, Cuenca, Iquitos, the jungle of Costa Rica, Barcelona, the desert of New Mexico. These are all places that you can visit to experience the potentially healing powers of sacred medicines. For $1200 dollars you can enjoy a two-day “Don Juan Teachings” peyote ceremony organized by a Polish man with the help of a “Huichol shaman” in the comfort of a hotel in Cancún. If you are looking for a deal, elsewhere along the Mayan Riviera, in Tulum, a young woman who self-identifies as a shaman provides peyote ceremonies accompanied by “Wixárika chants,” for only 45 euros! Or head further south for any number of retreats where you can rotate ayahuasca, San Pedro, peyote, kambô, and rapé. Choose one plant or many; it is a buffet of interchangeable ecologies and cultures administered through the hands of people who provide biographical abstracts to assure their capacity to safely officiate ceremonies with these plant and animal medicines.

The women are sexy, there are sweat lodges and tipis, chanting, eco-villages, yoga, massages, and vegan food.

From platforms like Instagram to alternative retreat sites, these plants and the cultural practices that promote their use are on full display. The women are sexy, there are sweat lodges and tipis, chanting, eco-villages, yoga, massages, and vegan food. It is a standardized menu for the globally mobile, upper class, and curious.

The cliché remains true: We live in a world in need of deep psychological healing and many of us live in societies and within cultures that do not offer us the answers to our crises. As women, we continue to be oppressed and desire liberation and spiritual connection; as urban citizens, we desire health and a landscape beyond asphalt. It sounds like a repeat of the 1960s and the first boom in psychedelics. Fifty years later, the existential search continues, and Indigenous cultural practices once more are understood and consumed as alternative ways of being in the world and with the planet. The second boom is here, but I fear that it is a boom on steroids with corporate financing, patents, and bioengineering on the horizon, and a much more mobile (at least pre-COVID) community of seekers.

With this in mind, what does it mean to partake in the buying and selling of these sacred plants? What are the implications of moving these “ancestral medicines” across various geographies? And how is it that those involved in these activities utilize notions of indigeneity, and often Indigenous associates, to add value to their circles and retreats, irrespective of authenticity, conflict, and power?

As a student of the history of Wixárika territory and culture, I have closely followed efforts to protect the sacred pilgrimage place of Wirikuta from the devastation of mining and agro-industry. It is this land in the Chihuahuan Desert that peyote is endemic to. For much of the consumer public, these medicines are divorced from their habitats, and this very fact is dangerous to their survival. In the case of peyote, I have yet to see its scarcity or slow growth cycle be properly acknowledged. Peyote’s condition is abstracted through a language of abundance; for it is abundance that the seeker desires. On the other hand, for most Indigenous communities, there is a clear relationship between these sacred plants and the historical and spiritual geographies they are rooted in. Territory and culture are not so easily disentangled.

Since 2010, the Natural Protected Area of Wirikuta and its surrounding region in the plateaus of north-central Mexico has faced the threats of a landscape that is changing through macro practices, like mining—the harms of which are heightened through the effects of climate change—and through micro practices, as seen in the over-extraction of peyote. Scale is undoubtedly important: Pipelines and industrial egg farms pose an immediate damaging effect to the land, while the effects of mining take a little longer to manifest, but remain in the water and soil for generations. In this way, peyote extraction by “hippies” is less pressing; yet, some researchers are beginning to demonstrate that extraction of peyote is also being fueled by global consumption of the plant in powder form, which allows it to travel greater distances, making it into the parties of Ibiza and a variety of ceremonies and retreats throughout the Americas.

As Wixárika lawyer, Santos Rentería, emphasized at the Chacruna’s Sacred Plants in the Americas Conference in 2018, peyote is part of “a whole”; it is not merely a plant, it is a being that is part of an ecological and cultural landscape dating back millennia. All elements affecting the individual peyote are also transforming the landscape as a whole. In the end, both the landscape and the individual plant are under threat, and their conservation must attend to this symbiotic factor. The struggle to protect the Chihuahuan Desert’s biodiversity is deeply related to the long-term conservation of peyote in its endemic geography; itself, the richest source of spiritual knowledge.

The Imperative for Horizontality and Decolonization

Yet, to this day, we often do not mention that the violence perpetrated by colonial and capitalist structures of economic and political power are sometimes accompanied by another side, represented by awe, curiosity, and even desire for the “otherness” of Indigenous cultures.

As Eduardo Galeano wrote nearly 50 years ago, across all Indigenous territories of the Americas run similar veins that have lived under assault for several hundred years. Yet, to this day, we often do not mention that the violence perpetrated by colonial and capitalist structures of economic and political power are sometimes accompanied by another side, represented by awe, curiosity, and even desire for the “otherness” of Indigenous cultures. This other side can be observed in the amply documented (mis)uses of sacred Indigenous plants and traditions, and it is past time that the global public interested in these matters makes space, listens to, and respects the perspectives and autonomy of Indigenous communities.

I return to the closing remarks at the Sacred Plants in the Americas Conference when Aukwe Mijarez of the Consejo Regional Wixárika (Wixárika Regional Council), moved the audience to tears when she reminded us that, as a Wixárika person, to not find peyote is to face the deepest sadness, the inability to cumplir, to meet agreements with the ancestors and provide the foundations for collective livelihoods: “More than just a plant, this is about the survival of a people! We do not want to be dressed up to be an exotic people, and for our culture to be prostituted and sold, but to be defended!”

So, what does a wider network of consumers mean in the face of scarcity?

I would like to suggest that the broadening global interest in these medicines requires a moment of pause and education in order to put into perspective the ecological and cultural footprint that accompanies the consumption of sacred plant medicines.

I would like to suggest that the broadening global interest in these medicines requires a moment of pause and education in order to put into perspective the ecological and cultural footprint that accompanies the consumption of sacred plant medicines. Many organizations and individuals have spent decades researching, advocating, and caring for these plants through various cultural perspectives and from various geographical locations. Increasingly, the “biocultural” approach promises a model for conservation and ecological restoration projects that are premised on multiple complementary knowledges and a greater balance in the relationship between humans and ecologies. It means defending the lands that sacred plant medicines are part of while respecting the knowledge of Indigenous peoples who offer generations of investment in understanding these medicines.

Undoubtedly, there is a deep need for psychological and physical healing for a much larger group of people who do not currently have access to the potentials offered by some of these medicines. This, too, raises questions about equity. Luckily, this matter is being addressed not only by a network of people who have long understood the benefits of these medicines for psychological and physical healing within Indigenous communities but also by practitioners of color who are committed to underserved populations. As we move forward with any conversations on decriminalization and conservation, these voices need to be front and center.

Across our differences, I see hope if we are able to agree on some of the following premises: 1) to protect the habitats that are the homes of these sacred plants and animals and, through social and political organizing, bring together concerted efforts toward the conservation and restoration of these very territories; 2) create and provide cultural and environmental education for the broader public to understand and respect mandates around the specificity of each medicine, its history, and the cultural context that frames its study, conservation, and use; and 3) prioritize practices that come from a place of humility, collaboration, and horizontality.

Those of us involved in these discussions and practices must work to better understand that coloniality is premised on the ongoing displacement, appropriation, and distortion of Indigenous land and culture. Following this, decolonization can only begin by listening and carefully working toward collaborative models across geographies and identities, always with full recognition of the autonomy and leadership exercised by Indigenous communities who have been the greatest custodians of these medicines.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?