- Participation in an Indigenous Amazonian-led Ayahuasca Retreat Associated with Increases in Nature Relatedness – A Pilot Study - March 21, 2024

- A Phenomenology of Subjectively Relevant Experiences Induced by Ayahuasca in Upper Amazon Vegetalismo Tourism - November 9, 2023

- The Pharmacological Interaction of Compounds in Ayahuasca: A Systematic Review - October 26, 2023

Ruffell, S. G., Netzband, N., Tsang, W., Davies, M., Butler, M., Rucker, J. J., Tófoli, L. F., Dempster, E. L., Young, A. H, & Morgan, C. J. (2021). Ceremonial ayahuasca in amazonian retreats—mental health and epigenetic outcomes from a six-month naturalistic study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 898. DOI 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.687615.

- Study Rationale

- Methodology

- Summary of Results

- Correlation Analysis With Number of Ceremonies, Length of Retreat, and Frequency of Ayahuasca Use Prior to Retreat

- Predictors of Change in Psychopathology

- DNA Methylation Analysis

- SIGMAR1 Methylation Correlation Analyses

- Integration with Extant Literature

- Memory Recall and Mental Health Outcomes

- Ayahuasca and Trauma

- Epigenetic Change

- Study Relevance

- References

Study Rationale

To date, no studies have assessed epigenetic change and mental health outcomes associated with trauma following psychedelic use. Our team therefore conducted a study to evaluate, through naturalistic means, whether ayahuasca improved mental health conditions related to trauma, and whether this was associated with epigenetic change. We assessed the severity of childhood trauma in participants to provide insight into whether ayahuasca could be used as a potential treatment for developmental trauma, as suggested by anecdotal evidence (Nielson & Megler, 2014).

We assessed the severity of childhood trauma in participants to provide insight into whether ayahuasca could be used as a potential treatment for developmental trauma.

Methodology

A prospective naturalistic study design was used to evaluate 63 participants who attended ayahuasca rituals at the Ayahuasca Foundation, located in the Amazon rainforest in Peru. Standardised questionnaires were administered to participants prior to their first ceremony (pre), the day after their last ceremony (post), and six-months after their final ceremony. Four ml of saliva was also collected under the guidance of researchers pre- and post- retreat for epigenetic analysis. Post retreat measures were completed on laptops in a quiet space at the retreat site on the morning before travelling back into Iquitos. The six-month follow-up questionnaires were collected electronically via email. Participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) (Beck et al., 1996), State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al., 1983), Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) (Neff, 2016), Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) (Evans et al., 2002), and the Sentence Completion for Events From the Past Test (SCEPT) (Raes et al., 2007) at all three time-points. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein et al., 1998) was completed at time point one and the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ) (Barrett et al., 2015) at time point two only.

Summary of Results

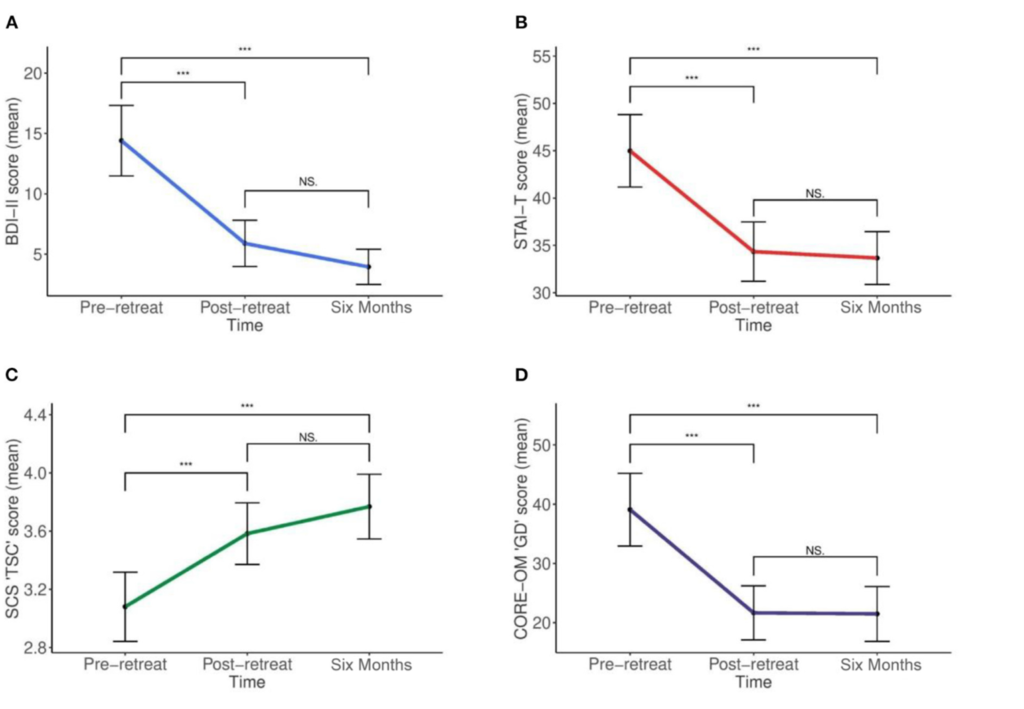

Mean outcome scores all differed statistically significantly between time points (see Figure 1, plates A-D) for the BDI-II: d = 1.15, p < 0.001; STAI-T: d = 0.87, p < 0.001; SCS: d = 0.78, p < 0.001; and the CORE-OM: d = 0.83, p < 0.001. Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons revealed a reduction in all severity scores from pre- to post- retreat for the BDI-II; STAI-T; and CORE-OM, which were all statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level. Six-month follow-up scores further reduced for the BDI-II; STAI-T; and CORE-OM, which were all statistically significant compared with pre-retreat scores at the p < 0.001 level, but not post-retreat scores (BDI- II, p = 0.153; STAI-T, p = 1.0; CORE-OM, p = 1.0), suggesting sustained improvement. For the SCS, there was an increase from pre to post retreat, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001); follow-up SCS score further increased and was significant compared with pre-retreat (p < 0.001), but not post-retreat (p = 0.138), again suggesting sustained improvement. Only total scores from measures were used in the analysis.

Figure 1

Changes in outcome scores over time

No significant changes in memory specificity were found on the SCEPT. However, new variables of total positive and negative memory scores for each time point were computed to assess changes in memory valance. Significant reductions in negative valanced memories were identified from pre-retreat to follow-up (p = 0.004), suggesting improvement over time.

Correlation Analysis With Number of Ceremonies, Length of Retreat, and Frequency of Ayahuasca Use Prior to Retreat

Pearson’s correlations were computed between number of ceremonies, length of retreat, and frequency of ayahuasca use prior retreat and improvement scores on the BDI-II, STAI-T, CORE-OM, and SCS. There were no significant correlations.

Predictors of Change in Psychopathology

To minimise the risk of type I errors, Pearson’s correlations were computed with CTQ and MEQ total scores and subscales and BDI-II change scores (the latter chosen as a proxy for all outcomes given similar patterns of findings across all outcome measures). Greater change in BDI-II post-retreat was correlated with higher overall CTQ scores (r = 0.318, p = 0.011 for overall population) scores. These figures were, however, not significantly correlated with BDI-II change at six-month.

DNA Methylation Analysis

BDNF analyses failed due to an error, therefore only SIGMAR1 and FKBP5 were analysed. The SIGMAR1 assay showed a statistically significant increase in DNA methylation across the 5 analysed CpG sites (paired t-test: t = 2.58, df = 38, p = 0.01). FKBP5 DNA methylation did not show any statistically significant change (p = 0.13).

SIGMAR1 Methylation Correlation Analyses

Methylation change scores were calculated for SIGMAR1 and Pearson’s correlation performed with CTQ total scores. There was a significant correlation (r = 0.387, p = 0.015), indicating those with higher childhood trauma had increased methylation changes in SIGMAR1 post retreat. In order to reduce the risk of type I errors, SIGMAR1 methylation changes were correlated with BDI-II as a proxy for all outcome measures; there was no significant correlation in this analysis.

Integration with Extant Literature

Ayahuasca dosing led to a statistically significant reduction in depression, global distress, and state and trait anxiety with scores post-retreat maintained at six-month follow-up. In addition, self-compassion scores also significantly increased and were sustained at follow-up. We hypothesised that change in mental health outcomes would be associated with change in overgeneral autobiographical memory (OGM). This inability to access specific autobiographical memories has been demonstrated to corelate with both Major Depressive Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Williams et al., 2007). More specifically, childhood trauma, particularly sexual trauma, has been found to be associated with the development of OGM in later life (de Decker et al., 2003; Kuyken & Brewin, 1995). In order to avoid retrospective accounts, Valentino et al. (2009) evaluated OGM in families with active social services input. Recruited through the Department of Human Services, children who had suffered abuse or neglect were found to exhibit more OGM. The idea that trauma could be a meditating pathway resulting in OGM was the basis of including the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) within the study inventory.

Memory Recall and Mental Health Outcomes

Although no change in memory specificity was identified on the Mean Sentence Completion for Events from the Past Test (SCEPT), general negative memory recall decreased between time point one and long-term follow-up. In a recent study, Weiss et al. (2021) found the reappraisal of challenging experiences was a strong mediator of change in psychometric outcomes. This construct resembles various psychotherapeutic techniques, including acquiring new meaning from traumatic events (Resick et al., 2016), assessing the accuracy of various belief systems (Hollon & Beck, 2013), encouraging psychological flexibility in order to derive meaning (Elliott et al., 2013; Hayes et al., 2011), and striving to achieve courage (Hollon & Beck, 2013). Continued investigation into the extent to which psychedelic-induced processes overlap with psychotherapy is warranted.

Ayahuasca and Trauma

It has been proposed that ayahuasca may be beneficial in treating PTSD and other disorders related to trauma (Nielson & Megler, 2014). It has been suggested that the acute psychedelic effects of the brew and recall of repressed memories may aid users in assigning a new context to traumas (Nielson & Megler, 2014). Ayahuasca use has been shown to elicit neural activation in limbic and higher cognitive regions involved in the formation of memories and emotional processing (de Araujo et al., 2012; Riba et al., 2006). Mechanistic theory, supported by preliminary data, has suggested that this process occurs via the modulation of SIGMAR1, with the alkaloids present in ayahuasca enhancing synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis as well as promoting memory reconsolidation and fear extinction through dopamine release (Inserra, 2018). In those with trauma-related disorders, there may be the potential for re-traumatisation if the user is in an inappropriate setting or mindset preceding use (Nielson & Megler, 2014). However, most of the evidence surrounding ayahuasca use in the management of trauma is anecdotal or speculative, with few studies examining memory recall.

Epigenetic Change

The epigenetic analysis in our study is the first to assess the impact of any psychedelic on epigenetics. The analysis indicated that drinking ayahuasca in an Amazonian retreat setting could impact the epigenetic expression of the SIGMAR1 gene. Epigenetic regulation of neuronal gene transcription, via methylation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), have been implicated in susceptibility to psychiatric disorders (Zannas & West, 2014). It is currently unclear if the mean increase in DNA methylation of 2.09% reflects actual changes in gene expression or suggests any significant impact biologically. Although increases in the DNA methylation of SIGMAR1 might result in receptor upregulation, hypermethylation, according to standard DNA methylation principles, usually leads to transcriptional silencing (Zannas & West, 2014). As with the above findings, further research with larger samples assessing both clinical and non-clinical populations is required to ascertain the impact of ayahuasca epigenetically.

This study is amongst the first to prospectively collect quantitative data concerning the impact of Shipibo-style Amazonian ayahuasca retreats on common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.

Study Relevance

This study is amongst the first to prospectively collect quantitative data concerning the impact of Shipibo-style Amazonian ayahuasca retreats on common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety. Given the recent surge in interest in Amazonian ayahuasca retreats, with large proportions of people seeking out the brew for its anecdotal effects on a number of common mental health difficulties, this study provides data in support of these claims. Although previous studies have evaluated the potential psychological mechanisms of change, this is the first to look at epigenetics as a biological mechanism of change, not only in ayahuasca but in any psychedelic. Recent studies have suggested that trauma can be passed on intergenerationally via epigenetic change (Yehuda & Lehrner, 2018) and our study indicates that further research is needed to fully establish whether ayahuasca could be a potential treatment for individuals with trauma symptoms. As retreat centres continue to operate as a thriving business and the medicalisation of ayahuasca seems increasingly likely (Psychae Institute 2021; Sacred Medicines 2022), information is required to better understand this intriguing brew, from potential biological impact to the psychological processes underlying its therapeutic effect.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

References

Barrett, F. S., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2015). Validation of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. Journal of psychopharmacology, 29(11), 1182-1190.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Ball, R., & Ranieri, W. F. (1996). Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of personality assessment, 67(3), 588-597.

Bernstein, D. P., Fink, L., Handelsman, L., & Foote, J. (1998). Childhood trauma questionnaire. Assessment of family violence: A handbook for researchers and practitioners.

de Araujo, D. B., Ribeiro, S., Cecchi, G. A., Carvalho, F. M., Sanchez, T. A., Pinto, J. P., de Martinis, B. S., Crippa, J. A., Hallak, J. E., & Santos, A. C. (2012). Seeing with the eyes shut: Neural basis of enhanced imagery following ayahuasca ingestion. Human brain mapping, 33(11), 2550-2560.

de Decker, A., Hermans, D., Raes, F., & Eelen, P. (2003). Autobiographical memory specificity and trauma in inpatient adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(1), 22-31.

Elliott, R., Greenberg, L. S., Watson, J. C., Timulak, L., & Freire, E. (2013). Research on humanistic-experiential psychotherapies.

Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., McGrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., & Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE–OM. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(1), 51-60.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. Guilford Press.

Hollon, S., & Beck, A. (2013). Research on psychodynamic therapies. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 6, 393-442.

Inserra, A. (2018). Hypothesis: the psychedelic ayahuasca heals traumatic memories via a sigma 1 receptor-mediated epigenetic-mnemonic process. Frontiers in pharmacology, 9, 330.

Kuyken, W., & Brewin, C. R. (1995). Autobiographical memory functioning in depression and reports of early abuse. Journal of abnormal Psychology, 104(4), 585.

Neff, K. D. (2016). The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1), 264-274.

Nielson, J. L., & Megler, J. D. (2014). Ayahuasca as a candidate therapy for PTSD. In The therapeutic use of ayahuasca (pp. 41-58). Springer.

Psychae-Institute. (2021). Home Page. Retrieved 19th November from https://www.psychae.org/

Raes, F., Hermans, D., Williams, J. M. G., & Eelen, P. (2007). A sentence completion procedure as an alternative to the Autobiographical Memory Test for assessing overgeneral memory in non-clinical populations. Memory, 15(5), 495-507.

Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2016). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. Guilford Publications.

Riba, J., Romero, S., Grasa, E., Mena, E., Carrió, I., & Barbanoj, M. J. (2006). Increased frontal and paralimbic activation following ayahuasca, the pan-Amazonian inebriant. Psychopharmacology, 186(1), 93-98.

Sacred-Medicines. (2022). Our Mission. Retrieved 19th November from https://www.sacredmedicines.earth/our-mission

Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, R., Vagg, P., & Jacobs, G. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Palo Alto, CA, Ed. Palo Alto: Spielberger.

Valentino, K., Toth, S. L., & Cicchetti, D. (2009). Autobiographical memory functioning among abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated children: The overgeneral memory effect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(8), 1029-1038.

Weiss, B., Miller, J. D., Carter, N. T., & Campbell, W. K. (2021). Examining changes in personality following shamanic ceremonial use of ayahuasca. Scientific reports, 11(1), 1-15.

Williams, J. M. G., Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Herman, D., Raes, F., Watkins, E., & Dalgleish, T. (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological bulletin, 133(1), 122.

Yehuda, R., & Lehrner, A. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 243-257.

Zannas, A. S., & West, A. E. (2014). Epigenetics and the regulation of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuroscience, 264, 157-170.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?