- 2024 Begins with Trepidation in Psychedelic Medicine and Markets - January 26, 2024

- This is How Jurema, a DMT-Containing Tree, Helped the Pankararé People Recover Their Land in Brazil - December 29, 2023

- The Triumphant Comeback of Psychedelics - July 24, 2023

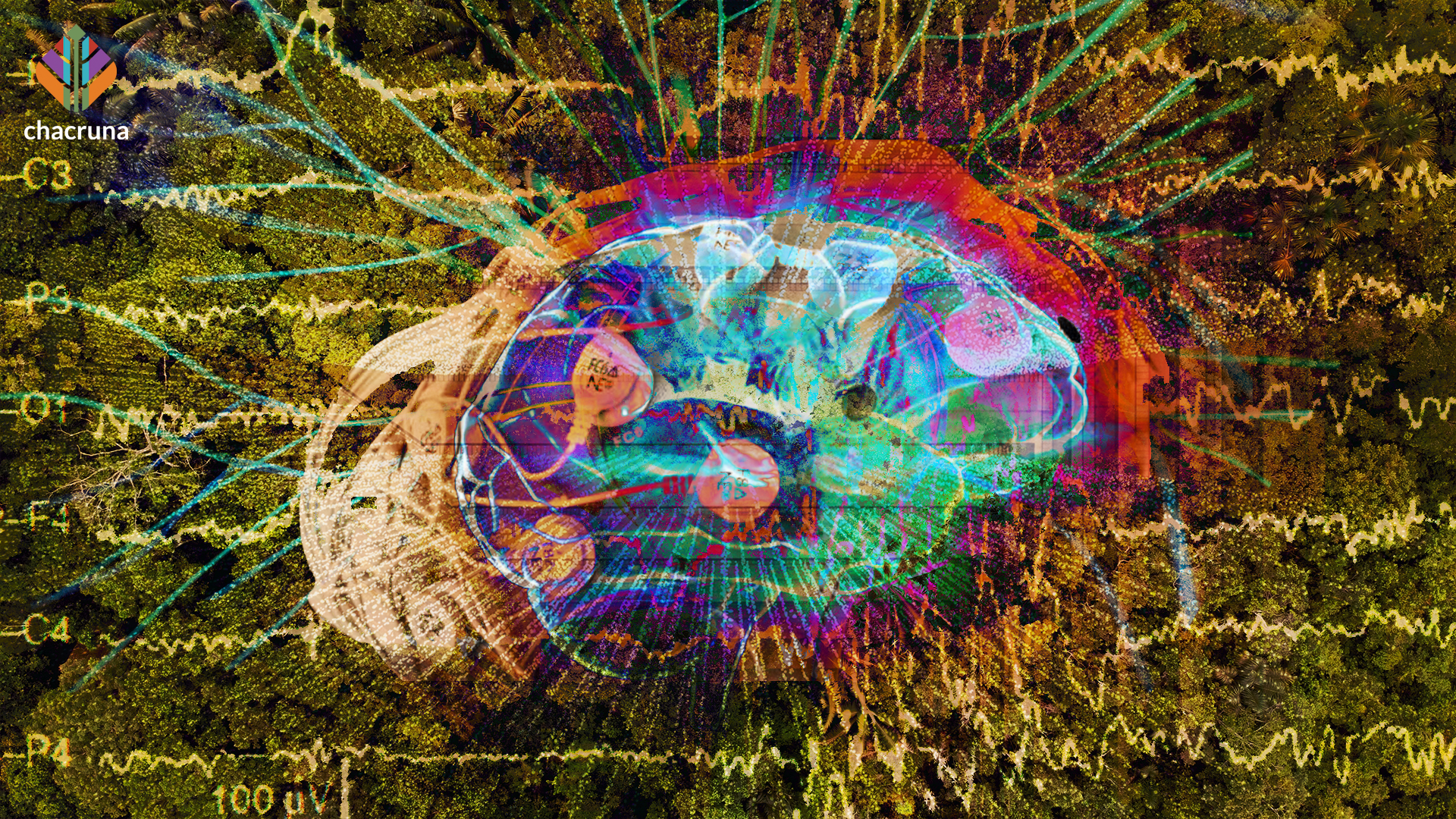

There was something surreal to the scene: A European researcher, his whole body covered in Indigenous people’s graphics, wearing a cap dotted with dozens of electrodes for encephalography (EEG). A member of the Huni Kuin village blows rapé (snuff) into the nostril of the white man, who is carrying a backpack full of equipment to record his brainwaves.

The so-called Expedition Neuron took place in April 2019, in Santa Rosa do Purus, State of Acre, in the Brazilian Amazon. The programming was an attempt to bridge the gap between traditional knowledge about ayahuasca uses and the consecration of the brew by science in the psychedelic renaissance. The most salient result of the initiative, so far, appeared in a controversial article about research ethics, not data.

The paper’s title in the journal Transcultural Psychiatry promised: “Overcoming epistemic injustices in the biomedical study of ayahuasca: Towards ethical and sustainable regulation.” Since publication on January 6, the article has generated more heat than light; perhaps because its critics are complaining out of the public’s reach, not in plain sight.

Authors Eduardo Ekman Schenberg, from the Phaneros Institute in Brazil, and Konstantin Gerber, from the Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP), question the authority of science by pointing out the difficulty of using placebo in psychedelic trials, the emphasis that neuroscientists put in molecular aspects, and the allegedly inadequately considered role of “setting” when it comes to safety, a subject about which scientists could learn a great deal from Indigenous peoples, according to the authors.

Join us for our next conference!

In their crosshairs stand out trials carried out in the last decade by the groups led by Jaime Hallak at the University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto (USP-Ribeirão) and by Dráulio de Araújo at the Brain Institute at the Rio Grande do Norte Federal University (ICe-UFRN), both specifically geared at gauging the effect of ayahuasca on depression. Asked to comment, researchers from those groups have not responded to emails or have otherwise declined to respond.

The antidepressive potential hitherto shown by DMT, the main psychoactive compound in the brew, is the focus of research in other countries as well, not only in Brazil. Other psychedelic substances, such as MDMA and psilocybin, though, are further down the road to get regulators’ approval as psychiatric medicines.

Given the obvious effect of psychedelic substances such as ayahuasca on the subject’s mind and behavior, Schenberg and Gerber argue, the double-blind strategy (the gold standard of biomedical research) faces an impasse: Both the volunteers and the researchers almost always know if the former received an active substance or not. This flaw would annihilate the supreme value conferred to such studies in the psychedelic field and by biomedicine in general.

Another point criticized by the authors lies in the decontextualizing and reductionism inherent in trials that take place in hospitals and laboratories, where the patient is surrounded by equipment and takes doses measured in milligrams per kilogram of body weight. Precision is illusional, they claim, and base their assertion on the error committed in an article (Osório et al., 2015) that mentions a concentration of 0.8 mg/ml and says further ahead it was 0.08 mg/ml.

A more ethical approach from the side of researchers would imply recognition of stewardship, joint and participative development of research protocols, co-authorship of scientific publications and intellectual property, and benefit sharing in case of revenues coming from treatments and patents.

The cultural sanitization of setting, on its own right, makes a tabula rasa of contextual elements (forest environment, chants, cosmology, rapé, dances, shamans) that, for peoples such as the Huni Kuin, cannot be separated from what ayahuasca has to offer and teach. By ignoring them, scientists are accused of dismissing everything that Indigenous peoples know about the safe and collective use of the substance. What is more, at the same time, they would be appropriating and disrespecting the traditional knowledge. A more ethical approach from the side of researchers would imply recognition of stewardship, joint and participative development of research protocols, co-authorship of scientific publications and intellectual property, and benefit sharing in case of revenues coming from treatments and patents.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

“The complementarity between anthropology, psychoanalysis, and psychiatry is one of the challenges of ethnopsychiatry (Laplantine, 1998),” argue Schenberg and Gerber. “The initiative to bring biomedical science to the forest can be criticized as an attempt to medicalize shamanism (Ramírez, 2020), but can also constitute a possibility of intercultural dialogue centered on innovation and solving ‘problem nets’ (Olivé, 2009).” The authors also claim:

It is particularly striking that biomedicine is now venturing into concepts such as “connectedness” (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018) and “nature-relatedness” (Forstmann & Sagioglou, 2017) as effects of psychedelics, thus once again approaching epistemic conclusions similar to earlier notions from Indigenous epistemologies developed from shamanic practices (Kopenawa & Alberts, 2013). The final challenge would thus be to understand the relation between community welfare and ecology and how this could be translated into a Western conception of integrated health.

The reactions coming from a few scholars willing to openly criticize the article and its grandiose ideas can be summarized with an old and malevolent academic tirade: There are good and new things in the article, but the good ones are not new, and the new ones are not good. Bringing EEG to the Acre forest, for instance, would not even begin to approach all the problems.

Schenberg is the liaison between the Transcultural Psychiatry article and Expedition Neuron, since he took part in the 2019 visit to the Huni Kuin and is the Brazilian counterpart in the EEG study led by Tomas Palenicek, a researcher from the National Institute of Mental Health in the Czech Republic. Here is a video presentation of the project.

“Konstantin [Gerber] and I are engaged in an innovative project with the Huni Kuin and European researchers, trying for more than three years to build an epistemically just partnership,” replied Schenberg by email when asked about the EEG-study compliance with ethical requirements put forward in their article. In a written presentation of Expedition Neuron, he claims:

In this first short and exploratory expedition, we confirmed that there is mutual interest from scientists and members from a traditional Indigenous culture of the Amazon to jointly explore the nature of consciousness and how their traditional healing works, including—for the first time ever—recordings of brain activity in a scenario many would consider technically too challenging.

We consider it of supreme value to jointly investigate how the Huni Kuin rituals and medicines affect human cognition, emotions, and group bonding, and to analyze the neural basis of these altered states of consciousness, possibly including mystical experiences in the forest.

Schenberg and his collaborators plan another expedition to visit the Huni Kuin to record multiple and simultaneous EEG samples of up to seven village inhabitants while taking part in ayahuasca ceremonies. The idea is to test the

very intriguing possibility that there is increased inter-brain synchronization while the participants and the maestro (or shaman or guide) jointly experience an altered state of consciousness mediated in great part by ancestral songs. Interpreted as a kind of gateway to the spiritual world by the Huni Kuin and other Amerindian peoples, ayahuasca is known to strongly and quickly strengthen community bonding and feelings of empathy or closeness to others.

Indigenous persons do not appear to have been consulted for the production of the article: there are no native voices, they are not co-authors, and we don’t have specific proposals of what a truly interethnic and intercultural research project would be.

Schenberg and Gerber’s purported goals have not convinced Brazilian anthropologist Bia Labate, director of the Chacruna Institute in San Francisco: “Indigenous persons do not appear to have been consulted for the production of the article: there are no native voices, they are not co-authors, and we don’t have specific proposals of what a truly interethnic and intercultural research project would be.”

According to Labate, even though Expedition Neuron has secured authorization to perform research, which is positive, this doesn’t suffice as an alternative epistemology to substitute for a scientificist and ethnocentric approach. Interethnic research, in her view, would imply promoting an ethnography that takes into serious consideration the Indigenous notion that plants are spirits, have proper agency, and that the natural world is also cultural, encompassing subjectivity and intentionality.

We all know that the beverage ayahuasca is not the same as freeze-dried ayahuasca; that the setting matters; that the rituals and the collectives taking part in them make all the difference. The anthropological literature has already raised the same points, or analogous ones, but its references were not taken into account by the authors.

Labate is also in disagreement with the idea that ayahuasca studies in Brazil have neglected recognizing those who first came to the brew: “From a global viewpoint, it is precisely a trademark and a distinction of Brazilian scientific research that there has indeed been dialogue with members of ayahuasca religions. Those are legitimate research subjects, too, not only native peoples.”

Schenberg and Palenicek took part in a 2020 panel with another anthropologist, French-Colombian Emilia Sanabria, from Healing Encounters, a project of the National Council of Scientific Research (CNRS) of France. Together with Leopardo Yawa Bane, a Huni Kuin, the three of them debated the EEG study at the 2020 Interdisciplinary Conference on Psychedelic Research (ICPR) under the title “Bringing the Lab to Ayahuasca.”

You can watch the panel here, in English

Sanabria then praised Schenberg and Palenicek for bringing up ethical questions related to ayahuasca research, mentioning that those are not new, as countless other botanical and medical studies have led Indigenous peoples to develop a framework for making such encounters fair and just, not just out of political correctness. First of all, she stated, traditional peoples consider that Western science and states have always denied recognition of their existence and knowledge. When recognition has been granted, if ever, it was exclusively in Western terms, effectively negating Indigenous ways of life.

Sanabria recommended pausing and asking whose interests are really being served and how to ensure actual reciprocity. After all, Indigenous terms and concepts are often untranslatable in colonial languages and boundaries, since many traditional groups don’t recognize the separation between individual and collective, between material and immaterial, and between nature and culture.

Isn’t there an inherent contradiction between standardization, on one hand, and the naturalistic setting, on the other? The catch,” she said, “seems to be that the emphasis there is still entirely on Western diagnostics, on mental illness, or whatever is happening somehow located in the brain, which is contrary to Indigenous understanding of ayahuasca.

The anthropologist quoted Daiara Tukano, saying that, for her people, ayahuasca is the fountain of all other knowledge, an invitation for researchers to really listen to Indigenous wisdom and grasp the entanglement of human and non-human existence. Then, Sanabria asked Schenberg and Palenicek directly on the issue of honoring Indigenous understanding of ayahuasca by situating the study in a naturalistic setting: “Isn’t there an inherent contradiction between standardization, on one hand, and the naturalistic setting, on the other? The catch,” she said, “seems to be that the emphasis there is still entirely on Western diagnostics, on mental illness, or whatever is happening somehow located in the brain, which is contrary to Indigenous understanding of ayahuasca.”

For Sanabria, securing ethical clearance is only the first step. Respectful collaboration would require further steps; for instance, that research be directly relevant for the Huni Kuin under their priorities, which have to be continuously renegotiated. Indigenous communities should be able to control, access, and steward the data coming out of the investigation, in light of the intellectual property rights sought by many psychedelic researchers.

The anthropologist went on to ask Schenberg and Palenicek what role the Huni Kuin had in designing the research protocol for the study and if they would appear as co-authors of future publications. Mentioning the acceleration of violence against Indigenous peoples in Brazil, she questioned: “Finally, does this study [Expedition Neuron], which [had] started 2 or 3 years ago, still have relevance in this moment of hunger and Covid?”

Sanabria repeated this point in a recent comment she posted on Twitter: “The Huni Kuin people are facing urgencies that are much more important than our epistemic (dis)agreements.”

When Sanabria confronted Schenberg and Palenicek with this line of questioning in the 2020 panel, she got generic replies; hardly examples of concrete benefits to the Huni Kuin. For instance, they said that science can help to prevent the patenting of ayahuasca.

From an anthropological point of view, there isn’t much difference between the EEG study among the Huni Kuin and the UFRN article showing the therapeutic effect of ayahuasca on depression that came under Schenberg and Gerber’s criticism, extending to the works by the group at USP-Ribeirão, too. The duo pointed out, for instance, the fact that UFRN researchers had indicated in their 2019 paper that 4 out of 29 trial subjects stayed as inpatients for at least one week at the university hospital, Onofre Lopes, in Natal (RN). With that, they raised the suspicion that safety in ayahuasca administration hadn’t been adequately handled.

“None of these studies tried to formally compare safety in the laboratory environment with any of the cultural ritual settings where ayahuasca is commonly used,” Schenberg and Gerber pontificated. “Yet, to the best of our knowledge, it has never been reported that 14% of people attending an ayahuasca ritual required a week of hospitalization.” The reason behind hospitalization, though, was trivial: suffering from treatment resistant depression, some patients had already been admitted to the hospital because of the severity of their disorder and remained in the clinic after the experimental intervention. In other words, the length of hospitalization was not a result of drinking ayahuasca.

This blog also questioned Schenberg about the apparent exaggeration in pinpointing a mistake that could be attributable to a typo (0.8 mg/ml or 0.08 mg/ml) in the 2015 article by the USP-Ribeirão group as a flagrant imprecision that would put in jeopardy the epistemic superiority conferred to psychedelic biomedicine. “If they had paid more attention to the testimony of volunteers/patients, maybe they would have noticed the fact,” countered the researcher at Phaneros Institute. “On top of the epistemic injustice against Indigenous peoples, there is epistemic injustice against volunteers/patients, which we discuss briefly in the article, as well.”

Schenberg has published many articles that could be attributed to the biomedical paradigm now in his crosshairs. Should his article with Gerber be seen as self-criticism related to his previous works?

I have always been a critic of certain biomedical limitations, and it was only with much effort that I managed to finish my postdoc work, for instance, without using placebo, in spite of the majority of my colleagues insisting that was what I should have done, otherwise, “it wouldn’t be scientific”…

In the end, their reasoning is circular: to use biomedicine as the ultimate criterion to respond to criticisms against biomedicine,” objects Bia Labate

“In the end, their reasoning is circular: to use biomedicine as the ultimate criterion to respond to criticisms against biomedicine,” objects Bia Labate. “The article does not solve what it purports to solve, but deepens instead the gap between Indigenous and biomedical epistemologies in advocating for new ways of doing biomedicine based on validation criteria coming from… biomedicine.”

Art by Trey Brasher.

————-

A slightly different version of this article was originally publish in Portuguese by Folha de S.Paulo in the blog Virada Psicodélica

Healing Encounters. (2022). Healing encounters [Homepage]. https://encounters.cnrs.fr/en/

Leite, M. (2020, November 19). Brasileiros apontam potencial da ayahuasca para prevenir suicídio [Brazilians point to ayahuasca’s potential to prevent suicide]. Virada Psicodélica. https://viradapsicodelica.blogfolha.uol.com.br/2020/11/19/brasileiros-apontam-potencial-da-ayahuasca-para-prevenir-suicidio/

OPEN Foundation. (2020, September 22). Bringing the lab to ayahuasca [Video file]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/JEaQ4Z7O6-Q

Osório, F. L., Sanches, R. F., Macedo, L. R., dos Santos, R. G., Maia-de-Oliveira, J. P., Wichert-Ana, L., de Araujo, D.B., Riba, J., Crippa, J. A., & Hallak, J. E. (2015). Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: A preliminary report. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr, 37(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1496

Palhano-Fontes, F., Barreto, D., Onias, H., Andrade, K. C., Novaes, M. M., Pessoa, J. A., Mota-Rolim, S. A., Osório, F. L., Sanches, R., dos Santos, R. G., Tófoli, L. F., de Oliveira Silveira, G., Yonamine, M., Riba, J., Santos, F. R., Silva-Junior, A. A., Alchieri, J. C., Galvão-Coelho, N. L., Lobão-Soares…Araújo, D. B. (2019). Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 49(4), 655–663. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/rapid-antidepressant-effects-of-the-psychedelic-ayahuasca-in-treatmentresistant-depression-a-randomized-placebocontrolled-trial/E67A8A4BBE4F5F14DE8552DB9A0CBC97

PSYRES Foundation for Psychedelic Science. (2019, July 22). Partnership of eccentric scientists with Huni Kui and Ashaninka Indigenous people [Video file]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/X0sgIM795_8

Sanabria, E. [@emsanabria]. (2022, March 7). Que pena que nossa conversa se resumiu assim para você @MarceloNLeite- gostaria resgatar o que você deixo de lado: o [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/emsanabria/status/1500981261816537102?s=20&t=7h79ITAuXIAsKmuHfJf1Zw

Schenberg, E. E. (2019). Showcase: Exploring the effects of psychoactive substances on brain and mental states with EEG. Expedition Neuron: Neuroscience in the Brazilian and Peruvian Amazon. Ant-Neuro.com

Schenberg, E. E., & Gerber, K. (2022). Overcoming epistemic injustices in the biomedical study of ayahuasca: Towards ethical and sustainable regulation. Transcultural Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634615211062962

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?