- A Homosexual Marriage Experience in Santo Daime - October 22, 2019

- The Muká Diet of the Yawanawá Indigenous People in Acre, Brazil - May 28, 2018

- A Homosexual Marriage Experience in Santo Daime - October 22, 2019

Five years ago, we got married in Rio de Janeiro in a religious ritual of Santo Daime. Recently, Shelby Hartman1 published an article in Chacruna about homophobia in ayahuasca circles. We also went through situations of symbolic violence, inside and outside the rituals. We have much to thank the church adepts for who helped us in organizing the ceremony. However, we cannot fail to mention situations that we consider today as homophobic.

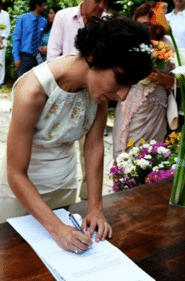

It was May 3, 2014. The place: a house in the middle of Tijuca Forest, in Alto da Boa Vista, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. At 10 a.m., we went downstairs to the table where the notary judge was. She would fulfill the bureaucratic function of making us legally married. We acquired similar civil rights to those of heterosexual couples. In 2011, in a historic decision, Brazil´s Supreme Court ruled that homosexual couples also have the right to marry legally, with the same rights and duties as heterosexual marriage.

After the civil marriage, the adapted Santo Daime religious wedding ritual took place. Our marriage did not take place in the break at a festival ritual at the hall of the church, as happens in the heterosexual marriages in Brazil of this religion.

After the civil marriage, the adapted Santo Daime religious wedding ritual took place. Our marriage did not take place in the break at a festival ritual at the hall of the church, as happens in the heterosexual marriages in Brazil of this religion.

We kept three hymns (considered to be sacred songs) of Padrinho Sebastião’s that are sung in heterosexual marriages, but we changed the texts read by the officiant. We selected the biblical passage Corinthians 13, which talks about love, replacing a conventional text of this church, Ephesians 5:23, according to which “the husband is the head of the wife.”

Each of the betrothed entered the ceremonial space with their respective members of the bridal party, while the guests sang the hymn “The Symbol of Truth.” All the people present sang 14 hymns from Santo Daime, selected by us. Guests wishing to drink ayahuasca could go to the altar to receive it. Along with us, several other people, mostly Santo Daime adepts, drank a small dose of the tea.

Five years later, we remember the steps taken within the Santo Daime churches that led us to this wedding ritual. Between 2010 and 2012, I, Lígia, lived in Mexico City. There, I went through a process of religious conversion and became a “fardada” (adept) of Santo Daime (Igreja do Culto Eclético da Fluente Luz Universal Patrono Sebastião Mota de Melo – Church of Eclectic Worship of the Flowing Universal Light—Sebastião Mota de Melo, Patron).

From the beginning, I was accepted as homosexual in this church. I agree with Cavnar2 that the ritual context (the setting) is very important in regard to inclusion or exclusion in the group, and the issue of feeling well received and accepted, or not, by leaders and by other members, as homosexual is something that changes the experience.

This congregation was a small group of urban youth whose social values were very different from those of more traditional Brazilian Padrinhos; there was already a homosexual couple in the group. I felt the acceptance of homosexuality; but, paradoxically and simultaneously, I felt the presence of Mexican patriarchy.

The Santo Daime churches, in general, are organized in a patriarchal and hierarchical manner. Women are driven to perform gender roles related to motherhood and discouraged from leadership positions. There is a predominant conservative heterosexual family ideal.

The padrinho of the Mexican church accepted my homosexual orientation, but there was an effort on his part to make me “appear to be” heterosexual, with a clear female gender identity and normative behavior. There was acceptance of homosexuals, but on the condition that they fit with established hegemonic cisgender norms.

I realized that the intention to fit homosexuals into heteronormative patterns came from the moralities of the leaders, and not from teachings of the plant spirits.

The Mexican church has received Brazilian Padrinhos and Madrinhas related to ICEFLU. Once, I asked a madrinha about her understanding of homosexuality. For her, it was a “social disease,” created due to imbalances between masculine and feminine. Another madrinha suggested to me to seek motherhood through a heterosexual relationship. In other words, she advised me to fit into heteronormative standards. I perceived that, for her, homosexuality was a kind of taboo, a behavior to be fixed. On the other hand, when I participated in rituals at the Mexican church, the plant spirits never prompted me to seek that correction. Then, I realized that the intention to fit homosexuals into heteronormative patterns came from the moralities of the leaders, and not from teachings of the plant spirits.

On one occasion, I participated with this group in a peyote ritual conducted by a Huichol Indian. At the end of the night, the face of a young woman, who I didn’t know then, appeared in my mind. After a few months, on a trip to Rio de Janeiro in 2010, I believed I recognized the young woman from the “spiritual vision.” Since that day, that woman became my girlfriend and, four years later, my wife. At the end of 2011, Klarissa visited me in Mexico City and became an adept of Santo Daime.

In December 2012, we lived together in Rio de Janeiro. At that time, we regularly attended one of the oldest churches of Santo Daime outside Acre State. In the Santo Daime rituals, we began to have spiritual visions and intuitions about our wedding ceremony. As a result, we decided to talk with the leaders of the church about the realization of the ceremony.

We talked at first with the madrinha, who did not oppose our union, despite her clear embarrassment. She emphasized that the ceremony could not take place in the church hall, because “that kind of ceremony doesn’t belong to the tradition of Mestre Irineu [the founder of Santo Daime] and Padrinho Sebastião [founder of the ICEFLU branch of Santo Daime].”She gave us permission, but expressed the need to address this with the padrinho of the church.

So, that was what we did. At the end of a ritual, we told him our story and he told us that he would have to ask permission from Madrinha Rita, Padrinho Sebastião’s widow and the most important leader in the religion, in his understanding. He would give us a definitive answer after this conversation. We agreed to the condition. We requested daime (ayahuasca) for the ceremony, and he initially did not oppose this. We commenced with the legal proceedings of the marriage. We made the invitations and gave them to church members, about 80 people in all.

We could feel, inside and outside the rituals, the opposition to our marriage from some church members.

We could feel, inside and outside the rituals, the opposition to our marriage from some church members. As an example, days before the ritual, an elder from the church, with whom we had a good relationship, called us, saying that, during a ritual, Padrinho Sebastião’s spirit told her that our marriage could not happen. However, in the same ritual, we had experiences with the plant spirit that led us to believe that our “spiritual guides,” including Padrinho Sebastião, agreed with our union. Weeks after the marriage, this woman left the church.

That episode was not the most discordant one. Days before our ceremony, the padrinho from the church scheduled a ritual for men on the same day as our wedding. This act was shocking to us because our male guests were expected to be present at that ritual, which would start at the same time as our ceremony.

When we went to talk to the padrinho, he claimed that we hadn’t confirmed the date with him. However, we had given the invitation to his family with the date on it. The madrinha was aware. Yet, in this conversation, the padrinho claimed that we had transformed the ceremony into a bigger event than he had imagined.

He suggested that we should have a small, more discreet ritual, where we would drink ayahuasca at a break from some ceremony, in the church itself, in a space called the “little house of the daime,” only in the presence of the officiant and two groomsmen and two bridesmaids. In other words, away from everyone’s eyes and “in the closet.” He even suggested that we change the wedding date.

On the other hand, the madrinha of the church confirmed the authorization of Madrinha Rita: “Yes, my daughter, you are authorized. Better to marry than to jump from branch to branch.”

Here, his conservative morals prevailed, and this attitude led him to try to prevent us from having a ceremony attended by church members. That situation was one of the greatest points of tension and conflict that involved the organization of our marriage. On the other hand, the madrinha of the church confirmed the authorization of Madrinha Rita: “Yes, my daughter, you are authorized. Better to marry than to jump from branch to branch.”

Despite this, the padrinho in Rio declined to provide the ayahuasca drink he once consented to supply to consecrate our union. We looked for another supplier and got the ayahuasca at the very place where the wedding ceremony would happen, which was the ritual space of another shamanic line linked to local indigenous peoples (Guardiões Huni Kuin also known as Tradições Xamânicas da América Indígena [Huni Kuin Guardians or Shamanic Traditions of the Indigenous America]).

After the wedding ritual and lunch, the number of male participants at the celebration diminished, as the men left to attend the ritual announced by the padrinho from the church. However, the party continued until the dusk, with the presence of women fardadas from the church, children, family, and friends; an unforgettable moment for us.

After few weeks, an old member of Santo Daime told us that our marriage had softened rumors and gossip about homosexuality among church members. We understood that making our relationship public had exposed the taboo of homosexuality.

At the time, there were other queer members from Santo Daime who chose to continue hiding this aspect of their lives from fellow members. We knew about some of them because of the gossip or because they felt comfortable opening with us because we are also gay.

Despite all the conflicts and symbolic violence we endured, we did get married in an adapted ritual, and were respected as a couple by the other adepts. We believe that, due to the marriage ceremony, there was a relative social change regarding the acceptance of homosexual couples in this church.

Despite all the conflicts and symbolic violence we endured, we did get married in an adapted ritual, and were respected as a couple by the other adepts. We believe that, due to the marriage ceremony, there was a relative social change regarding the acceptance of homosexual couples in this church. On the other hand, there continued to be a conservative and heteronormative hegemonic morality. In our experience, we have seen a lesbian couple and a gay male couple who are Santo Daime Church leaders from “Padrinho Sebastião’s line”; however, some of these leaders present publicly as heterosexuals in order to avoid conflicts related to homophobia.

We believe that socio-anthropological research should be encouraged in order to determine whether homosexual-led churches offer a more welcoming environment for homosexuals and transgender people. This is because we have experienced for ourselves how important a welcoming setting is for LGBTIQI+ adepts engaging in personal healing and self-knowledge processes.

Join us at the Psychedelic Liberty Summit

References

- Hartman, S. (2019). Why LGBTQI+ members are creating their own ayahuasca circles. Chacruna.net. Retrieved from https://chacruna.net/why-lgbtqi-members-are-creating-their-own-ayahuasca-circles/ ↩

- Cavnar, C. (2018). Ayahuasca’s influence in gay identity. In B. C. Labate, C. Cavnar, & A. K. (Eds.), The expanding world ayahuasca diaspora: Appropriation, integration and legislation. New York City, NY: Routledge. ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?