In relation to psychedelic drug experiences, “set and setting” refers to an individual’s mindset and the physical and social environment in which the drug experience takes place. While personalities such as Timothy Leary and Al Hubbard have been recognized for their contributions to the history of “set and setting,” pioneering women researchers remain in the shadows.

It is rather striking that the work of Joyce Martin, Margot Cutner, and Betty Eisner is so little known and rarely discussed, in contrast to that of their famous collaborators, Ronald Sandison, Thomas Ling, and Sidney Cohen, respectively. This article highlights their work and their impact on this new emerging therapy in the 1950s and 1960s. All three women devised a therapeutic approach with their patients that was comprehensive, benevolent, and non-intrusive, and that broke radically with traditional methods.

“Set and Setting”: Its Origins

In the 1950s, some people in the medical community began to reconsider the methodology applied to psychotherapies performed using LSD. The self-experimenting psychiatrists generally recounted very positive experiences, which often took place in their own homes or offices, spaces that were welcoming and comfortable. They were free to come and go, and do as they please, and they had a prior theoretical knowledge of LSD, its effects, and their duration. If the accounts of the self-experimenters gave prominence to the state of euphoria, this was not the case in the experiments carried out on their patients, whether healthy or sick. In these cases, people felt anxiety and even terror. Faced with these results, certain therapists attempted to improve protocols, and in doing so, brought psychiatric practices into question.

In this new framework, which took into account the physical and emotional context, or “set and setting,” therapists gave consideration to the patients, their history, and their accounts of the experience.

In this new framework, which took into account the physical and emotional context, or “set and setting,” therapists gave consideration to the patients, their history, and their accounts of the experience. Patients were informed of the effects of the substance, the room where the experiments took place was decorated strategically, and patients were allowed to bring personal items with them into the examination room. Another person stayed with them during the entire session, keeping a watchful eye.

On the other hand, with traditional therapies, the demeanor of the personnel was “disciplined” and distant. The hospital rooms were white, lit by fluorescents, and lacking in any decoration. Some patients were even strapped to the bed. The subjects, often mentally ill, had to submit to the experiments without having received any background information and were subjected to a battery of onerous tests. By the late 1950s, the dominant explanation for the effects of LSD was a “psychotomimetic” concept, which aimed to simulate psychosis, thus confining the understanding of the subjects’ reactions to a solely pathological interpretation.

By proposing a new interpretation of the effects of LSD, this time directed towards a therapeutic goal, and by creating a new way of administering the drug, some therapists transformed LSD-assisted psychotherapies.

The Pioneering Women in the History of “Set and Setting”

Joyce Martin (1905-1969)

Joyce Martin was a Freudian psychoanalyst. A pioneer in the use of LSD in psychotherapy, she started her research in 1954, both in her private practice and at the Marlborough Day Hospital in London.

In 1964, Martin published an article in which she distinguished her therapeutic method from that of Sandison and Ling; most notably this method brought “direct and active support to the patient of his emotional needs when necessary” (Martin 1964). She developed a particularly controversial therapeutic method, in which she acted as a mother to the patient. In this scenario, the patient was encouraged to regress to the infant stage, while Martin provided an active and loving presence. Martin insisted that the response to the patient’s emotional insufficiency was not artificial. She stated that:

we are not just giving a dummy, but something nearer to the original breast and the beginning of a love relationship. […] This is our aim, therefore: to develop the transference relationship as quickly as possible to enable the ego strengthened and allow the previously unbearable feelings to be accepted and assimilated into the conscious personality, thus relieving the conflict and curing the symptoms and eventually integrating the personality.

With her assistant Pauline McCririck, they developed a system they called “fusional therapy,” which consisted of lying beside their patients “holding them in close embrace, as a good mother would do to comfort her child” (Grof & Grof 2010:42).

Margot Cutner (1905-1987)

Margot Cutner, née Kuttner, (1905-1987) was a Jungian psychoanalyst of German origin. Having received a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) from Hamburg in 1936, she fled Nazi Germany for England, where she anglicized her name. She trained with Elsa Gindler, a pioneer in body therapy and started her own psychoanalyst practice. One of the techniques she developed involved finding the most comfortable position for the patient, free from all tension or stress (Cutner 1953). In 1955 she joined the Powick Hospital in Worcester, on the team of Ronald Sandison. A special department was built at this hospital to foster LSD research.

In 1959, Cutner presented her therapeutic method. She observed that the research material emerging under the influence of LSD, “far from being chaotic, reveals, on the contrary, a definite relationship to the psychological needs of the patient at the moment of his taking the drug” (Cutner 1959). She emphasized this point: “it is obvious that it would not be safe to give the drug without adequate supervision to anyone who was not on fairly good terms with his own unconscious.” Cutner expressed serious reservations about the overly repetitive use of LSD in an attempt to break the psychic resistance of the patient. In her practice, certain patients, under treatment for two years, received only two or three sessions with LSD.

Her special attention to the body and its manifestations made her sensitive to the need for contact by the individual under the influence of LSD: at a certain level of regression caused by the substance, “it is obvious that the contact by touch, the only thing the patient can understand at such times, revives and represents his first experiences of security in the physical embrace of the mother” Thus “To obtain needed reassurance it is, at times, not even enough for the patient to feel the analyst’s hand touching him, but he himself may have to touch the analyst, or his clothes, etc.” Cutner, the psychoanalyst, paid attention as well to her own demeanor during the sessions, making sure to act in the most gentle and welcoming manner possible so that the patient might trust her completely. She was especially attentive to her own facial expressions, which were meant to express love and the absence of judgment.

“I swore I would never do to a patient what was done to me…I would do it gently.”

Betty Eisner

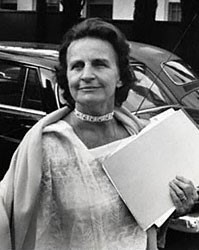

Betty Eisner (1915-2004)

On November 10, 1955, she became Sidney Cohen’s first guinea pig.. Her second session took place in January, 1957. This time, she explored the therapeutic potential of LSD. For her, left alone, the end of the session took on a deeply depressive dimension: “I had an awful experience.” She recounted how she eventually decided to contact Cohen, seeking (emotional) support. However, he didn’t take her seriously, even when she indicated her risk of suicide, and advised her just to have some rest. “I clearly remember telling him that it wouldn’t look good for the research if the psychologist who was the subject committed suicide. He was unimpressed,” she recounted.

In two sessions, Eisner had experienced both the frustration of having a battery of tests done and not being able to just let herself go with the substance, and subsequently the terrors that it could produce without adequate support. In the next two sessions, she decided to use only a very low dose, 25 μg, which brought her out of her depression and gave her a “mystical experience.” After that, she was convinced to use low doses in her practice, quite the opposite to her American colleagues, who were developing “psychedelic therapy” at high doses. “The beauty of the low-dose LSD was that it enabled a person to let go as much as he or she wanted. Perhaps just a little bit at first, then a little more the next time, and finally they would allow it to happen completely. […] We kept giving them sessions until they did,” Eisner recounted.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

In addition to requiring that someone stay with patients throughout the session and that doses be low and raised progressively, she was the first to write about the usefulness of playing music during the sessions. Finally, she insisted that two therapists, a man and a woman, be present in order for the patient to see them as parents and project onto the couple their feelings that they were experiencing.

In 1997 she proposed a third concept to add to “set” and “setting”: “matrix,” representing simultaneously the environment the patient is in at the time of their psychedelic experience as well as their past environment and that into which they will evolve once the treatment is finished (Eisner 1997).

Conclusion

These three women had an important impact on improving the methods of administering LSD. While well-known during their careers, Joyce Martin, Margot Cutner, and, to a lesser degree, Betty Eisner were gradually erased from research on the history of ‘set and setting’ and psychedelics. Their work is essential to understanding the major changes brought to LSD-assisted therapy during the period and highlights the role of women and their attention to the bodies and emotions of their patients.

Article translated by Robert Savery.

Art by Karina Alvarez.

References

Cutner, Margot. 1953. “On the Inclusion of Certain ‘Body Experiments’ in Analysis”. British Journal of Medical Psychology 26(3‑4):262‑77.

Cutner, Margot. 1959. “Analytic Work with LSD 25”. Psychiatric Quarterly 33(4):715‑57.

Eisner, Betty Grover. 1997. “Set, setting and matrix”. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 29(2):213‑16.

Eisner, Betty Grover. 2002. Remembrances of LSD Therapy Past. [unpublished manuscript].

Eisner, Betty Grover. 2005. “The Birth and Death of Psychedelic Therapy”. P. 91‑101 in Higher Wisdom: Eminent Elders Explore the Continuing Impact of Psychedelics. New York: State University of New York Press.

Grof, Stanislav, et Christina Grof. 2010. Holotropic Breathwork: A New Approach to Self-Exploration and Therapy. New-York: State University of New York Press.

Martin, Joyce. 1964. “L.S.D. Analysis”. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 10:165‑69.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?