- The Emergent Field of Psychedelic Chaplaincy - April 19, 2022

- Preparing Ourselves for the Psychedelic Future with Berra Yazar-Klosinski - November 3, 2021

- Stewarding Psychedelic and Ecological Biospheric Wisdom with Deborah Parrish Snyder - October 13, 2021

Deborah Parrish Snyder is the co-owner and publisher of Synergetic Press, an independent publishing company that has been producing cutting-edge books in the fields of ecology, sustainability, psychedelics, consciousness, and cultural anthropology for over 35 years. Recently, Synergetic Press published Psychedelic Justice: Toward a Diverse and Equitable Psychedelic Culture in collaboration with Chacruna. Beyond her publishing work, Deborah is also vice president of the Institute of Ecotechnics, a non-profit geared towards harmonizing technology with the global biosphere. There she has helped manage a number of ecological demonstration projects as well as host conferences on ecological trends.

In this interview, Deborah shares the history of her work with the Institute of Ecotechnics, detailing her journey and how she first came to start publishing books in the fields of ethnobotany and psychedelics. She further touches upon her vision to create greater cohesion between the ecological and psychedelic spaces, helping to foster the understanding that we are not separate from Nature and thus ought to steward it better.

Jasmine Virdi: Firstly, I think many in the psychedelic community might not know who you are, especially because you’re working behind the scenes as a publisher, helping to disseminate the voices of others rather than your own. For that reason, as well as knowing personally that over the years you’ve been involved in many different projects the world over, I’d like to give you the opportunity to share some of the context around your work.

Deborah Parrish Snyder: For me, the main lines have been publishing books with Synergetic Press, and in landcare with the Institute of Ecotechnics, a non-profit focused on harmonizing the “technosphere” with the “biosphere,” finding approaches to how we use/design technology to work in harmony with the ecological needs of the Earth. I started travelling once I finished college in 1980, buying a one-way ticket to France. Within a year, I encountered an international group of people looking for a new way to live and learn that ran the Institute of Ecotechnics. They held a conference on the Solar System at the farm where I was working and living in southern France, and the following year on the Cosmos, with speakers including Buckminster Fuller, James Lovelock, Richard Dawkins, Lynn Margulis, and Albert Hofmann.

The Institute built a series of projects spanning the globe, with projects in different biomes. For example, they had an ocean-going research ship named the Heraclitus, which continues to this day, studying different regions of the Earth’s oceans, as well as a sustainable forestry project in Puerto Rico. I was particularly involved from ‘84 to 2020 with the savannah biome project, working on a cattle and horse station in the Northwest Kimberley region of Western Australia for about 30 years, developing sustainable pastoral management practices.

After a decade of hosting conferences and managing various projects, the Institute constituted a cadre of forward thinkers who came together to design and build the Biosphere 2 project in Oracle, Arizona. Biosphere 2 contained seven biomes within a three-and-a-half acre closed-ecological system. Each biome was a carefully created replica of one of the various ecosystems on earth, including a tropical rainforest, a savannah, a desert, a marshland, and even an ocean complete with a coral reef. Technologically and ecologically ambitious, it was constructed during 1987–1991, being the largest laboratory for global ecology ever built.

JV: I’m also curious how you first came in contact with the renowned ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes. For many in the psychedelic community, he is considered a foundational figure, although I don’t think he would’ve considered himself that way. Beyond Schultes, I know you come into contact with Ralph Metzner too. Did these encounters serve to propel you into the niche of psychedelic publishing?

DPS: Richard Evans Schultes was invited to be a speaker in 1979 at an Ecotechnic conference on jungles held in Penang, Indonesia. At the conference, he spoke about the disappearing cultures and lore of the Amazon rainforest, and John Allen, director of the Institute and one of our authors at Synergetic Press asked what could be done to help the situation.

Schultes pointed to the research vessel Heraclitus and suggested that they take the ship to the Amazon on an ethnobotanical expedition to meet the shamans and conduct an ethnobotanical expedition to collect and gather knowledge about the plants and their uses. Between 1979-1981 the Heraclitus was in the Amazon. A few of the Institute team were trained to do plant pressings and collections in the jungle by Sir Ghillean Prance, renowned botanist, for whom I later published a book he edited, White Gold: the Diary of a Rubber Cutter in Brazil. Dennis McKenna and Wade Davis spent some part of their first exploration in the Amazon from the Heraclitus base.

Over the years, leading figures in these specialized realms have brought their manuscripts to me, including Schultes and the environmental activist Tony Juniper. This was in the mid-80s and by then I was the Director of Educational Programmes at the Institute’s Biosphere 2 project in Tucson, which was where I had started an imprint devoted to publishing books around the new science of biospherics, alongside Synergetic Press. Schultes had his first book, Where the Gods Reign, an anthropological overview of the Amazon rainforest ecosystem, ready to go to press when he walked into my office with it. My immediate reaction was, “I can’t wait to publish that for you,” and he was pleased because all other publishers had wanted him to write stories about his adventures rather than publish it as it was.

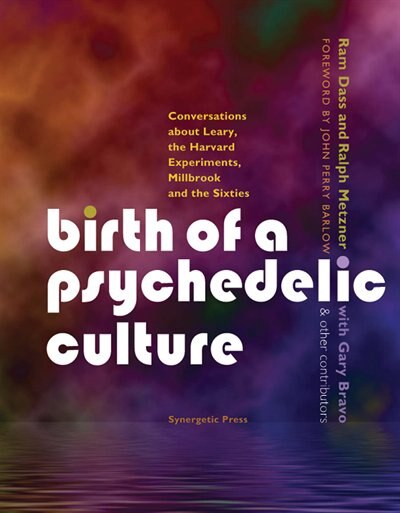

I told him it would be an honor to publish his book, which we did in 1986. Later still, we brought out the companion volume, Vine of the Soul, a photographic essay accompanied by detailed descriptions of the Indigenous use of medicinal and other sacred plant substances. The book opened me up to ethnobotany, which I had previously never heard of. At the time, not too many other people had heard about it either, and I thought they should, so we kept publishing books in that area. One thing led to another and eventually we came to publish Ayahuasca Reader edited by Luis Eduardo Luna and Steven White. After that we published Birth of a Psychedelic Culture, a conversational memoir in which psychedelic counterculture figures Ralph Metzner and Ram Dass reflect on Leary, the 60s, and the Harvard experiments.

I met Ralph at Synergia Ranch, the intentional community where I live, after he was finishing up from a workshop that was held here. We had a great conversation, and I asked him, as I always ask, if he had a book that he was writing. And indeed, he had this book that was a conversation between him and Ram Dass. Ralph had told me that despite having an agent, no major publisher had wanted to publish the book because it was conversational, and even worse, it was about the 60s! So we published Birth of a Psychedelic Culture in 2010, which I considered to be a cornerstone.

That book was the beginning of a beautiful relationship which invited other authors in the psychedelic space to notice what we were doing. At the time, there were not very many publishers putting out books on psychedelics, mostly because they were largely illegal and conventional publishers did not see the market. I also had enough knowledge about the subject matter that I didn’t suffer from the taboos held by many and was not afraid to publish books on psychedelics. For me, they are valid and vital tools that help us to understand our inner and outer worlds, and I wanted to be sure that some of the most knowledgeable people on these subjects were getting their work out there where there was little to find of substance.

JV: I’m curious about your personal connection with psychedelics. I know that your interest in ethnobotany partially relates to ecology and is a way of safeguarding knowledge about plants and the environment, but you publish books on psychedelics more broadly. What caused you to publish in this area?

DPS: Ayahuasca, the plant medicine that we first started publishing books about, was something I had never experienced, and so for me publishing on it genuinely started from an ecological and anthropological interest. Because the cultures and Indigenous lifeways of the Amazon rainforest were and still are quickly disappearing, I felt it important to document and preserve this wisdom in some way. It is largely from the ecological, biospheric perspective that I approach everything, and I believe that psychedelics have an important role to play in the ecological crisis because they enable embodied experiences of interconnection.

“Psychedelics have enhanced my biospheric understanding and appreciation for the inner and outer worlds of life.”

Deborah Parrish Snyder

Psychedelics have enhanced my biospheric understanding and appreciation for the inner and outer worlds of life. Additionally, I have such a huge appreciation for the knowledge and the understanding that people have around these plants as well as for the plants themselves, and as such, have taken an oath to protect that knowledge in some way.

The knowledge shared in our books offers tools and guidance to help us navigate the times we live in. My hope is that our press will serve as a beacon on real solutions to the challenges we face collectively.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

JV: I’m curious about your experience as a woman who’s been working in the psychedelic/ethnobotanical and ecological space for many years. Have you seen a change in the way women participate in these spaces and how that shapes the discourses around them?

DPS: In some sense, the Women’s Visionary Council (WCV) introduced me to this whole problem. It was in 2006 when Albert Hofmann celebrated his 100th birthday and the first major symposium on LSD was held in Basel, Switzerland in his honor. My friend Mariavittoria Mangini was supposed to present at the Basel conference, and would have been just one of five women presenting out of 75 speakers. For Annie Oak and the other handful of women present, they decided to stop waiting to be invited and put on a colloquium where the majority of speakers would be women. The seeds were planted for what is now the WCV. Quite a few women who are now recognized leaders and scholars in the field gave some of their first public talks at WVC Congresses, including Berra Yazar-Klosinski, Amy Emerson, and Ana Elda Maqueda. Bia Labate was also invited as a visiting scholar to several early colloquia.

“Women are actively filling the void that has been left by the aging patriarchal society with their much-needed energy and wisdom.”

Deborah Parrish Snyder

To answer your question, I feel that one of the biggest changes is that women stopped waiting to be invited and simply took a seat at the table. It’s taken a couple of decades, but now there is a robust community of women stepping in, taking charge, forming their own organizations, doing what they feel called to do and being empowered to do so. Women are actively filling the void that has been left by the aging patriarchal society with their much-needed energy and wisdom. Women are on the move, organizing conferences and running publishing companies, like Synergetic Press, which is largely a women-led organization. My take on it is we are finding a rebalancing of power by filling this space. It’s not a takeover, but power needs to be taken and leadership needs to emerge that understands the power of diversity in our society to evolve a world more in balance with ourselves and with Nature.

JV: Since you publish books on both psychedelics and ecology, I wonder if it is one of your goals to build a bridge between those two communities.

DPS: I’d like to inspire biospheric thinking—that is, conceiving of ourselves and Nature as a complex whole, in the next generation, many of whom are using psychedelics to inform their creativity and personal growth. I’m interested in the term “ecodelics,” introduced by Richard Doyle in his book Darwin’s Pharmacy, that points to psychedelics’ ability to encourage a more interconnected view of the world. Psychedelics can unify one’s self with the world of life, showing us that we are—as Indigenous peoples throughout the world already know—we are Nature.

JV: Well, thank you. I always like to give people the opportunity to share beyond the confines of the questions that I asked so is there anything that you’d like to add?

DPS: I feel that it is important that we build bridges between generations, bringing elder wisdom, including Indigenous elders, and those in the contemporary psychedelic movement together in community discussions, symposiums, salons, and conferences. One of the consequences from the War on Drugs is it created a couple-decade gap between generations having access to the elders, those who have experience and advice to share.

Join us for our next conference!

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?