When we think of the history of psychedelics in Canada, the work of prominent men such as Abram Hoffer, Ewen Cameron, Humphry Osmond, and “Captain” Al Hubbard comes to mind. Almost unknown is Dr. Florence Nichols, a Canadian psychiatric physician and missionary who, throughout her fascinating career, used LSD to treat mental illness on three different continents.

Meet Florence Nichols

Colourful, radiant, electrifying, vigorous. These are words that have been used to describe Florence Nichols. She was known to infect others with her enthusiasm for spirituality and psychiatry. As a psychiatric missionary, Nichols tended to cross boundaries, whether they be gender, national, ethical, or disciplinary.

“Nichols ignored prescribed gender roles and pursued training in a psychiatric context dominated by men.”

Seeing herself as the first female psychiatric missionary, Nichols ignored prescribed gender roles and pursued training in a psychiatric context dominated by men. Driven by her passion to help others, she left for India in 1946 to establish a psychiatric unit at the Christian Medical College in the city of Vellore. India had long been a destination for Canadian women missionaries, but Nichols’ particular emphasis on psychiatric issues was quite novel. This openness to new places and experiences, and passionate devotion to her spiritual mission, led her to employ a variety of physical and psychological treatments in her psychiatric practice. When LSD came to her attention in the 1950s, Nichols saw it as an effective and efficient tool for helping patients.

Following Dreams to India

Born in 1913, Nichols had dreamed of becoming a missionary since she was a child. “I never breathed a word about my desire to be a missionary to anyone, not even my Mother or Father,” she later said, “It was my private, treasured secret… But I knew it was what God wanted me to be.” Knowing that her parents did not approve of this path, she quietly pursued medicine while hoping that one day this would allow her to follow her dream. She received her Bachelor of Arts from the University of Toronto in 1934 and her medical degree in 1937. During a surgical internship, Nichols realized that she was more concerned with her patient’s mental lives and decided to pursue psychiatry. After earning a Diploma in Psychiatry in 1941, she worked at the Ontario Hospital in Toronto until she finally mustered the courage to apply to the Missionary Society of the Church of England. By 1946, she was on her way to India to help build a new department of psychiatry at the Christian Medical College in Vellore.

Psychiatry was not a priority for physicians in Vellore, and the College lacked infrastructure and funding for mental health treatment. They were not quite sure what to do with Nichols at first. She spent her initial years in Vellore struggling to learn the local language, Tamil, and familiarizing herself with local customs. To this end, her colleagues suggested that she visit the small village of Mattathur, near Vellore. She spent a happy five weeks living there in a small earthen hut while assisting as a nurse. The Christian Medical College did not have beds dedicated to psychiatric patients, and Nichols used a nurse’s pantry as her office. Over time, she carved out a niche for psychiatry at the College and was given more rooms and assistants.

“Nichols sought to reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness by showing kindness to patients.”

Florence Nichols returned to North America in 1950 to receive further psychiatric training at the University of Philadelphia and to find more funding for the Christian Medical College. In 1955, she travelled back to Vellore, and finally began her goal of setting up a fully developed psychiatric department at the College. As the head of the department, Nichols sought to reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness by showing kindness to patients, while also enhancing treatment options. The department came to offer a wide range of treatments that were common in psychiatry at the time, effectively blurring the lines between biological and psychological approaches to mental illness. Nichols practiced psychological therapies rooted in insight, such as psychoanalysis and family therapy, and employed physical therapies such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and insulin coma therapy. She also used barbiturates to facilitate psychoanalysis.

LSD: A New Way to Help People

This familiarity with a variety of psychiatric practices put Nichols in a good position to recognize the unique value of psychedelic medicine. Nichols was introduced to LSD through a colleague in the late 1950s. Like many psychiatrists at the time, she took the drug herself. During her first LSD experience, she relived an episode from when she was four months old. Her mother had mistakenly left her out on the porch in the winter, and she was very cold. The story was confirmed by her mother, and Nichols became enthusiastic about the therapeutic potential of this new experimental drug. LSD “makes you re-live things almost from birth, and I mean re-live,” she later said. After her first experience, Nichols felt that LSD had taught her more about herself in four hours than she had learned in 700 hours of psychoanalytic training. She began to use it to treat certain patients in Vellore.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Reliving Birth in Nottingham: Frank Lake and Clinical Theology

Unfortunately, Florence Nichols did not publish about her work with LSD. She had planned to write a long article and even a book about her use of psychedelic therapy, but it seems this plan did not come to fruition. Her approach to LSD therapy, though, would have been heavily influenced by her collaboration with Frank Lake, a British physician who, in the late 1940s, was the superintendent of the Christian Medical College. In turn, she introduced him to her unique combination of Christianity and psychiatry, which incorporated Christianity into her psychiatric practice, based on her conviction that “a firm Christian faith increases ego-strength.”

In the early 1950s, Lake returned to England where he pursued psychiatric training, including with Ronald Sandison and his work with LSD at Powick Hospital near Worcester. While using LSD in his practice throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Lake became astonished to find that, as Nichols had experienced, many of his patients reported reliving their birth trauma under LSD. Skeptical at first, he eventually started taking these experiences seriously when details from the reports of patients were later confirmed by mothers and other witnesses. He also learned that other psychiatrists made similar observations with LSD, such as Stanislov Grof. Certain psychoanalysts, such as Otto Rank, had previously argued that being born constituted a significant trauma for infants that impacted their subsequent personalities. Picking up on this tradition, Lake came to understand LSD’s therapeutic value in terms of its ability to reveal how one’s birth trauma resulted in particular behavioral patterns.

“Clinical Theology was a response to the growing realization that clergy members were often unequipped to handle more pressing psychological problems.”

When Nichols’ mother became ill in 1959, she left Vellore to return to Canada. The next year she travelled to England to work with Lake. Together they developed “Clinical Theology,” a framework for educating clergy members about mental health. While psychotherapy was becoming more socially acceptable in the 1960s, many people still relied on church leaders to ease their mental distress. Clinical Theology was a response to the growing realization that clergy members were often unequipped to handle more pressing psychological problems. Lake felt that the advice of ministers and the medication of psychiatrists served only to temporarily tranquilize a person’s worries, leaving the deeper roots of mental illness intact. The aim of Clinical Theology was to provide the tools to recognize and address these deeper roots. Lake travelled around England giving seminars to members of clergy and he established a Clinical Theology Association in 1962.

In addition to serving as an educational program, Clinical Theology evolved into a complicated mixture of existential philosophy, Christian theology, and psychoanalysis. In 1966, Lake published Clinical Theology: A Theological and Psychiatric Basis to Clinical Pastoral Care, which outlined the practical and theoretical dimensions of Clinical Theology. The 1160-page volume drew on his observations from LSD therapy to articulate the relationship between birth, psychiatric disorders, and Christian faith. Many of these observations came from LSD sessions with clergy members. Recognizing the importance of building a trusting relationship and a comfortable set and setting, Lake started these LSD sessions with prayer and Christian ceremonies.

For Lake, psychiatric therapy was about confronting one’s deepest and most painful emotions, and he identified these painful encounters with Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection. By “lifting the veil of repression,” LSD helped patients experience the roots of these emotions in birth. Lake also noted his own ecstatic LSD experience, in which “‘God’ in the ground of [Lake’s] being was sheer bliss,” but he did not think that LSD caused spiritual experiences. Rather, the drug merely allowed one to relive positive or negative experiences from birth.

A Missionary at Home

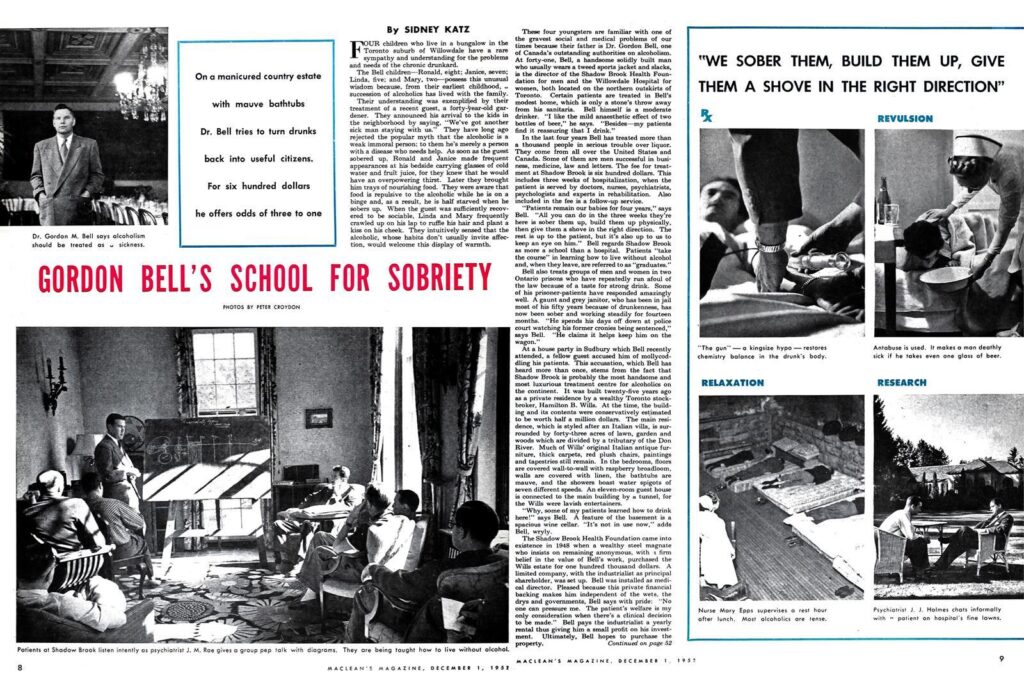

When Nichols moved back to Canada in the early 1960s, she continued to practice LSD therapy and teach Clinical Theology. In Toronto, she took a position at the Bell Clinic, a private hospital that centered on treating addiction. By early 1963, she had used LSD to treat over 100 patients suffering from alcoholism. According to Nichols, the majority of these patients had obtained sobriety, while others were making progress.

In Canada, Nichols was not shy about promoting LSD to the news media. In 1962, she appeared on a Canadian TV program that documented a woman’s experience of LSD therapy at Toronto Western Hospital. “No case is hopeless with LSD,” she told a reporter in 1963; “It brings not only awareness but also revelation, insight, reintegration and a lessening of anxiety.” Nichols also used psilocybin in her practice to help patients recover memories from birth and infancy.

LSD “brings not only awareness but also revelation, insight, reintegration and a lessening of anxiety.”

Florence Nichols

In addition to her work at the Bell Clinic, Nichols organized and conducted seminars in Clinical Theology throughout Ontario. Sponsored by the Canadian Mental Health Association, the seminars featured lively re-enactments of encounters between pastors and those seeking advice. The goal of these re-enactments was to help clergy members recognize specific psychiatric disorders. Apparently, Nichols was a very convincing performer.

By the mid 1960s, negative publicity surrounding LSD use in Canada led the director of the Bell Clinic to end the LSD program. LSD became illegal in Canada in 1968, and Nichols stopped using it in her psychiatric practice. Continuing her missionary work, she travelled to Singapore in 1968 to provide psychiatric training to clergy members. In the mid-1970s, she moved to British Columbia where she treated sex offenders in a maximum-security prison.

Nichols had a creative side too. She wrote engaging memoirs about her experience in India. In her later years, she wrote a book that examined her life from the perspective of her poodle, Barney. She passed away in 1987.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

A Canadian Psychedelic Pioneer

Florence Nichols had an adventurous and productive career as a psychiatrist. She clearly achieved her dream of helping others. But due to her role as a Christian missionary, her story raises complicated ethical questions about situating her desire to help people within the larger context of colonialism. Still, by treating over 100 patients with LSD at the Bell Clinic and by working to publicize LSD’s therapeutic benefits, Nichols was an early proponent of psychedelic therapy in Canada. We should therefore remember her name alongside of the male Canadian pioneers of psychedelic therapy.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?