- Psilocybin Mushrooms in Mexico in Danger of Extinction - July 9, 2021

- Seeking a True Shaman in the Sierra Mazateca - March 8, 2021

I have done field work in the Mazatec region since 2009, and in all these years, I have only seen two types of psilocybin mushrooms for sale in the city of Huautla de Jiménez. However, the article “Seeking the Magic Mushroom” (1957) describes the use of at least seven different species of psychoactive mushrooms in Mexico. One of these species is today in danger of extinction.

The banker and ethnomycologist Gordon Wasson and his wife, Valentina Pavlovna Wasson, spent part of their lives exploring the relationship between fungi and human cultures. In the 1950s, they were interested in identifying an inebriating mushroom that pre-Hispanic peoples called, in Nahuatl, teonanácatl, “the flesh of gods.”

Recordings are now available to watch here

After an extensive literature review, Valentina and Gordon Wasson concluded that the word teonanácatl could actually refer to several species of mushrooms unknown to science. For example, a text on the lexicon of the Zapotec language, published by Father Juan de Córdoba in 1572, suggested that there were at least two arboreal species of intoxicating fungi (Heim & Wasson, 1958, p. 33).

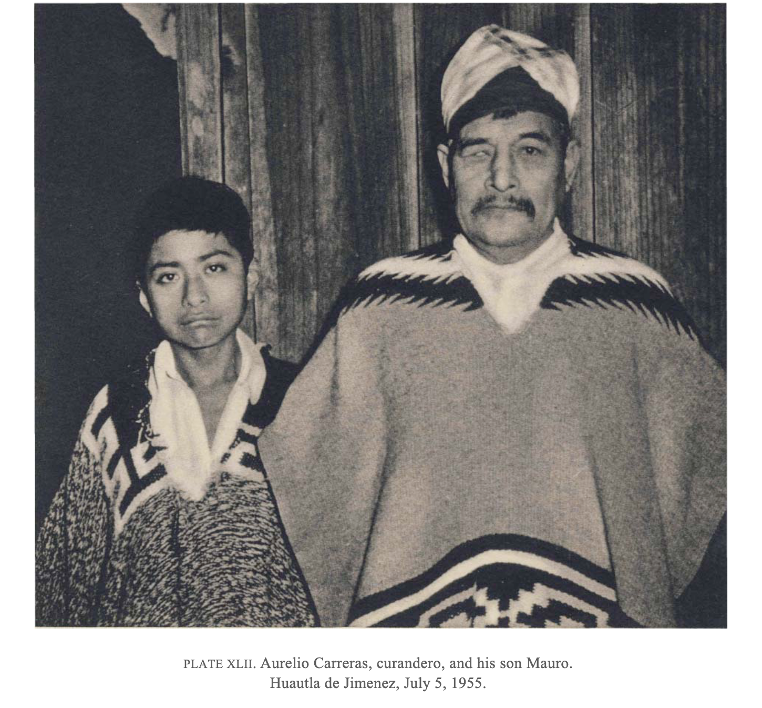

In August 1953, the Wasson family traveled together with the anthropologist Robert Weitlaner to the Mazatec region of Oaxaca to look for specimens of these fungi and correctly identify them. That year, the rains were particularly scarce, making it difficult to find the mushrooms. Despite the few rains, the team of researchers managed to find out that at least four types of fungi were used in rituals in the region, obtained a few specimens, and attended a divination ceremony with the shaman Aurelio Carreras.

The mushrooms collected in Huautla in 1953 were sent to Roger Heim in his laboratory at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. The French mycologist identified three different species among the specimens sent by the Wassons: Psilocybe mexicana, Psilocybe caerulescens and Psilocybe [Stropharia] cubensis. However, none of the samples submitted made possible the identification of an arboreal fungi (Heim, 1956a).

Gordon Wasson returned to Huautla with photographer Allan Richardson between the months of June and July 1955. Shortly after arriving in the region, the banker traveled through a ravine and found a pile of “landslide” mushrooms (Psilocybe caerulescens) growing on the rotten sugar cane bagasse.

That same night, June 29, Gordon Wasson first experienced the effect of mushrooms in a ceremony officiated by the famous Mazatec shaman María Sabina. A detailed account of these expeditions can be read in the second volume of Mushrooms, Russia and History (1957), Gordon Wasson and Valentina Pavlovna’s masterpiece.

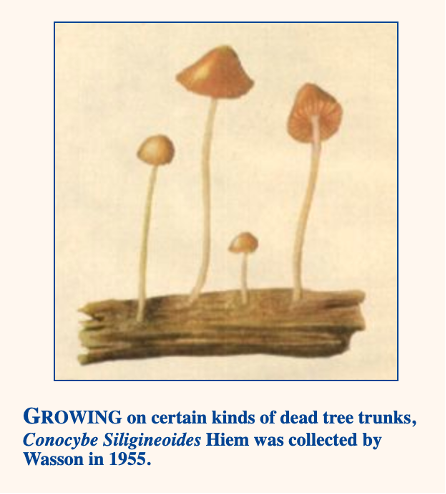

On the morning of Tuesday, July 5, 1955 Gordon Wasson asked Aurelio Carreras to get him specimens of the fungus that grows on the rotten branches of the ya’nte tree (Saurauia) (Heim & Wasson, 1958, p.195). Aurelio claimed that in order to collect them he had to travel to a distant place, more than five hours by mule from Huautla, so the banker offered him 100 pesos in exchange for a couple of these mushrooms. Mauro, Aurelio’s son, immediately mounted his mule to go to his ranch in the municipality of San José Tenango. Mauro returned to Huautla on Thursday, July 7, in the afternoon with five specimens of mushrooms.

Gordon Wasson claimed that he had eaten the smallest of these specimens and had managed to perceive the distinctive taste of psychoactive mushrooms. The four remaining specimens were sent to Roger Heim, a pair dried and a pair preserved in liquid. In his field diary, the banker wrote, “the five mushrooms @ 20 pesos each, must be about the most expensive ever” (Wasson, 1955).

The French mycologist examined the specimens sent by Wasson and gave to this fungus the scientific name of Conocybe siligineoides. In Mazatec it is called ta’a ya, “attached to the tree” (Heim, 1956b). “Ta’a ya” is the vernacular name for the mushrooms that grow on trees; in this case, two species: Psilocybe yungensis and Conocybe siligineoides. Psilocybe yungensis grows on several species of trees. Conocybe siligineoides grows only on a Saurauia tree called ya’nte in Mazatec; this is why, in many sources, they call this mushroom “ya’nte” (Heim & Wasson, 1958, p.p. 195–197) The four specimens sent by Wasson to Paris in 1955 are the only ones of this species that have been observed by professional mycologists.

Large amounts of fungi are required in order to isolate their active substance. In preparation for his trip to the Mazatec region in 1957, Gordon Wasson wrote to his interlocutors in Huautla, asking them to get as many of the four types of mushrooms as possible.

The banker asked Aurelio and his son to go out and look for the rare species that grows on the tree and begged him not to cut them, since he wanted to study them in the place where they sprout, even if it was necessary to spend the night at the ranch (Wasson & Martínez, 1957). On that occasion, the ethnomycologist was unable to obtain more specimens of Conocybe siligineoides, nor was he able to do so on his subsequent expeditions.

In 1958, Gordon Wasson offered a “very big gift” of 500 pesos to Aurelio if he would take him to see the mushrooms where they grow, no matter how far it was and no matter how much it rained

In 1958, Gordon Wasson offered a “very big gift” of 500 pesos to Aurelio if he would take him to see the mushrooms where they grow, no matter how far it was and no matter how much it rained (Wasson & Martínez, 1958). That year, in July, Gordon Wasson’s team managed to obtain, near the town of Rio Santiago, several specimens of a type of fungus that grows on the rotten trunks of various tree species.

In Mazatec, this fungus is also designated by the term ta’a ya, “attached to the tree,” but the local population clearly differentiates it from the one that grows on the trunk of the ya’nte (Saurauia) (Heim & Wasson, 1958, p.197). The arboreal fungi collected by Wasson in that expedition corresponded to a species previously located in Bolivia by the mycologist Rolf Singer and whose scientific name is Psilocybe yungensis.

Roger Heim published the results of his research in the book, Les champignons hallucinogènes du Méxique [The Hallucinogenic Mushrooms of Mexico], at the end of 1958. Gordon Wasson stated in this publication that Conocybe siligineoides had “disappeared from the vicinity of Huautla due to the progression of current deforestation” (Heim & Wasson, 1958, p. 54).

To date, we only have two proofs that these mushrooms contain psilocybin. First, Wasson’s testimony where he claims to have perceived the particular taste of psychoactive mushrooms in the specimen that he tested. Second, the Mazatec healer María Sabina confirmed their use in healing rituals in 1957 by recognizing them in Roger Heim’s watercolors that were published in LIFE magazine; the only images we currently have of these mushrooms.

Since then, psilocybin has been found in other species of Conocybe that are known by the common name of “cone-head mushrooms.” Despite extensive field work in the area, Gastón Guzmán, a Mexican mycologist specializing in Psilocybe, was unable to collect new specimens of Conocybe siligineoides (Guzmán et al., 1998).

The regulation prepared by Mexican authorities for the protection of native species of flora and fauna (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010) contains four categories that cover a range of species, from those that need special protection (Pr) to those that are probably extinct in the wild (E). This standard recognizes Conocybe siligineoides as a species in danger of extinction (P). Several species of Psilocybe are on this same list, either as endangered (P), threatened (A), or subject to special protection (Pr). The main risk factor for these fungi is deforestation caused by logging and changing land use for agricultural purposes.

It cannot be ignored that the demand for religious, therapeutic, and scientific uses has contributed to the progressive disappearance of these species.

It cannot be ignored that the demand for religious, therapeutic, and scientific uses has contributed to the progressive disappearance of these species. New business opportunities have arisen due to the possible legalization of psychedelics in the United States. Faced with this situation, academics and local leaders ask for recognition of the contribution of the population of the Sierra Mazateca to the “discovery” of these substances.

Today in the Sierra Mazateca, you can buy mainly two types of mushrooms with psychoactive properties: the “San Isidro” mushrooms (Psilocybe cubensis) that grow on cow excrement; and the “landslide” mushrooms (Psilocybe caerulescens) that grow on bagasse or on loose soil after a mudslide.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Today in the Sierra Mazateca, you can buy mainly two types of mushrooms with psychoactive properties: the “San Isidro” mushrooms (Psilocybe cubensis) that grow on cow excrement; and the “landslide” mushrooms (Psilocybe caerulescens) that grow on bagasse or on loose soil after a mudslide. The “little birds” mushrooms (Psilocybe mexicana), the first species to have been cultivated in Roger Heim’s laboratory, are nowadays difficult to obtain in Huautla.

In the trips that I have made as an anthropologist to the Sierra Mazateca in the last decade, I have listened to several people who assure me that it is increasingly difficult to find mushrooms that grow in the forest.

In the trips that I have made as an anthropologist to the Sierra Mazateca in the last decade, I have listened to several people who assure me that it is increasingly difficult to find mushrooms that grow in the forest. These people say, for example, that when mills without mechanical motors were used and the streets were not paved, P. caerulescens fungi arose in greater quantities from rotten bagasse and from mudslides on the roads.

The works of Roger Heim and Gordon Wasson showed us the effects of deforestation on the biodiversity of the Mazatec region as early as the 1950s. The disappearance of jungles and forests has accelerated in the world and, with it, the probable extinction of several species, including some types of psychoactive mushrooms. Finding a way to benefit from fungi without limiting their diversity would be a small but necessary contribution to taking care of our planet.

Please donate to the Psychedelic Renaissance Documentary

Art by Trey Brasher.

References

Guzmán, G., Allen, J. W., & Gartz, J. (1998). A worldwide geographical distribution of the neurotropic fungi: An analysis and discussion. Annale de Museo Civico de Rovereto Archeologia, Storia, Scienze Naturali, 14, 189–280. http://www.fungifun.org/docs/mushrooms/Psilocybe/World_Wide_Distribution_of_Magic_Mushrooms.pdf

Heim, R. (1956a). Note sur les Champignons divinatoires utilisés dans les rites des Indiens Mazatèques [Note on the divinatory mushrooms used in the rites of the Mazatec Indians]. Journal d’agriculture tropicale et de botanique appliquée, 3(3–4), 207–209. doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/jatba.1956.2301

Heim, R. (1956b). Note sur des Champignons divinatoires utilisés dans les rites des Indiens Mazatèques [Note on the divinatory mushrooms used in the rites of the Mazatec Indians]. Journal d’agriculture tropicale et de botanique appliquée, 3(5–6), 320–325. doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/jatba.1956.2313

Heim, R., & Wasson R. G. (1958). Les champignons hallucinogènes du Mexique [The hallucinogenic mushrooms of Mexico]. Paris: Éditions du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. https://sciencepress.mnhn.fr/fr/periodiques/archives-du-museum-national-d-histoire-naturelle-7eme-serie/6/les-champignons-hallucinogenes-du-mexique-etudes-ethnologiques-taxinomiques-biologiques-physiologiques-et-chimiques

Wasson, R. G. (1955). Field notebook #4, (1/3[CC9] ) [MGdT10] (English). The Tina & R. Gordon Wasson Archives, Botanical Library, Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

Wasson, R. G. (1957, June 10). Seeking the magic mushroom. Life Magazine. http://www.imaginaria.org/wasson/life.htm

Wasson, R. G., & Martínez, H. (1957, February 25). [Correspondence] Gordon Wasson to Herlinda Martínez, (Spanish). The Tina & R. Gordon Wasson Archives, Botanical Library, Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

Wasson, R. G., & Wasson, P. V. (1957). Mushrooms, Russia and history (Vol. 2). New York City, NY: Pantheon Books. https://www.newalexandria.org/archive/MUSHROOMS%20RUSSIA%20AND%20HISTORY%20Volume%202.pdf

Wasson, R. G. & Martínez, H. (1958, June 9). [Correspondence] Gordon Wasson to Herlinda Martínez (Spanish). The Tina and R. Gordon Wasson Archives, Botanical Library, Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?