By Way of Introduction

This article is the result of an ongoing exercise of analysis that I have carried out using the concrete forms of my training as a researcher in the social sciences, but also as a member of the Mazatec Indigenous people; an analysis from within that seeks to render visible the acts of memory and resistance in ritual, as well as in daily life, against the constantly reconfiguring mechanisms of domination that seek to control Mazatec culture, with a special focus on ritual healing with Psilocybe mushrooms. The subject requires new analytical perspectives to understand the role of indigenous societies and their sacred plants in the evolution of the capitalist world.

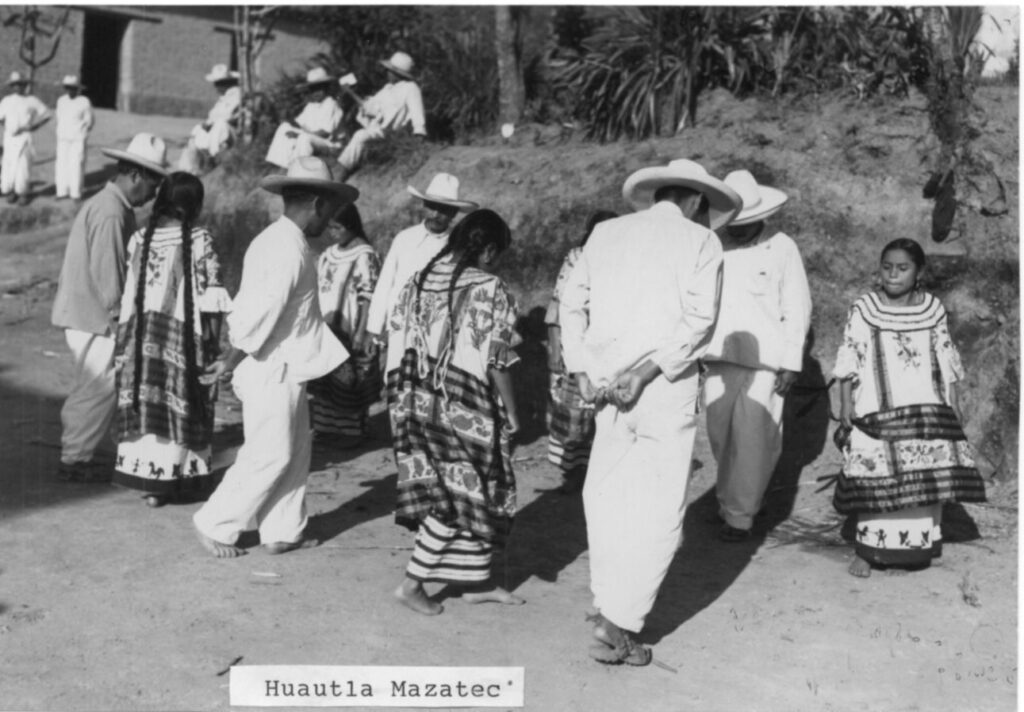

These narratives are nourished by anecdotes and sensationalized facts that have developed into a sacred tourism industry that strengthens and reproduces the monetization of Mazatec culture, with Huautla de Jiménez as its capital.

Some Disclaimers

The ascent to the Sierra Mazateca is always full of expectations and never disappoints, with all that one can experience there. From wild animals running along the road to the classic stories about María Sabina and the so-called “magic mushrooms,” as the Psilocybe that grow in the rainy season are commonly called. It is during this season that foreigners of different nationalities and social strata arrive in the region in search of sacred experiences with the Ndi shi tjo, “Little ones who sprout,” in the Mazatec language. Consequently, certain sectors of the population have assumed an accomodating attitude that has as its common denominator a mystical discourse about the magic mushrooms. These tales almost always take as their starting point the moment when Gordon Wasson “discovered” the mushroom ritual with María Sabina. Images of naked hippies are invoked at Puente de Fierro, followed by assurances that Bob Dylan and John Lennon came in search of this Mazatec “priestess,” and then complaints about how the arrival of foreigners in the 1960s caused the breakdown of a tradition that had remained secretive and incorruptible since pre-Hispanic times. These narratives are nourished by anecdotes and sensationalized facts that have developed into a sacred tourism industry that strengthens and reproduces the monetization of Mazatec culture, with Huautla de Jiménez as its capital.

At the same time, an increase in tensions has been observed within the population as a result of competition to attract tourists, whether selling mushrooms, serving as intermediaries with the Chjota Chjine (“people of knowledge”), or developing friendly and sympathetic relationships with foreigners

This situation has strained the relations between regional political groups, since control of this market translates into profiting from cultural tourism and a series of state programs aimed at exploiting an alleged ethnic authenticity. At the same time, an increase in tensions has been observed within the population as a result of competition to attract tourists, whether selling mushrooms, serving as intermediaries with the Chjota Chjine (“people of knowledge”), or developing friendly and sympathetic relationships with foreigners. In this way, the logic of capitalism has transformed the region, displacing traditional kinds of work associated with the land and creating new forms of underemployment and poverty.

After reading these assertions—many of them already noted by researchers, tourists and local people themselves—it would be prudent to ask: What is left to be discovered that, after the 65 years since this process began, remains latent and perceptible within the daily life of the Mazatec peoples? In concrete terms, the answer I seek is aimed at revalorizing the memory and voices of people who have been overlooked by history.

Mazatec Memory: An Act of Resistance

Serapio’s house is found on a narrow lane in Santa Cruz de Juárez township in the Huautla municipality. This fellow Mazatec takes the last sip from his cup of coffee and entrusts me with part of his life story, which is a constant back-and-forth between past and present; between the trade in coffee and mushrooms. He says he used to plant coffee beans on his plot, like so many others, when there was still good money to be made. But that, he says, is now over. When he was very young, he learned to “cure with mushrooms,” and knew the rules for letting them do their work. After almost an hour of speaking, his final comment was as follows:

Those of us who know how to cure with mushrooms, learned it gradually; you don’t pick it up just like that, like those who go around saying they know everything about healing just because they want to make some money or show off in town. Who knows if what they say is true, or if they are just deceiving people?… I learned from my parents and my grandparents; it is something that comes from long ago, from those who lived before me. That’s why those of us who really know, keep it a secret, so that it doesn’t get lost, so that it continues to heal people.

Remembrance is a guide through which the mushroom ritual allows a return to mythical origins, out of which are determined the subjective present and future; a time outside the logic of “modern” (capitalist) times.

His story echoes so many others collected in the Sierra Mazateca, allowing us to conclude that sacred plants and rituals fulfill their purpose by evoking the past in ways that only acts of memory can provide, despite their inherent uncertainty (Ricoeur , 2000). Remembrance is a guide through which the mushroom ritual allows a return to mythical origins, out of which are determined the subjective present and future; a time outside the logic of “modern” (capitalist) times. In this sense, the Psilocybe mushroom ritual allows us to make a leap into the past as a way of challenging the banality and short-sightedness brought by “modernity”: a continuous struggle of memory against forgetting (Tischler, 2010, p. 54).

I should explain that this “Mazatec memory,” determined as it is by diverse forms of knowledge closely related to territory and natural resources, is neither static nor trans-historical. It is constantly reconfigured through the same set of transformations that the population has undergone as a result of various historical processes, including capitalist development in the region, but with which, nevertheless, it is in constant tension.

What influenced María Sabina to decide to host the velada that night in June of 1955 that would leave Wasson so thunderstruck?

María Sabina: The Voice of the Other

When Cayetano García sent word to María Sabina that her knowledge was required to carry out a velada (evening session), she accepted without question. However, realizing that the person to whom she would give the mushrooms was unknown and foreign to the Mazatec community, a moral dilemma emerged that contested her beliefs and ways of perceiving the world. What influenced María Sabina to decide to host the velada that night in June of 1955 that would leave Wasson so thunderstruck? It is a question that, even 65 years later, continues to raise doubts and concerns. My intention in this inquiry is to move beyond mere revisionism about the encounter between Sabina and Wasson and to try to understand the ways in which power relations and ritual practices were intertwined, and continue to intertwine, in dictating María Sabina’s actions.

Belonging to a different context from that of so-called “modern societies,” though no less violent, Maria Sabina was aiming to ensure her own and her family’s survival.

The proper ways of perceiving one’s world and culture are determined by an intimate relationship with the sacred but, at the same time, by different forms of domination historically established by the ruling classes and taken on as forms of community relationship by the working class. Therefore, it is possible to consider that there were two immediate factors that determined her actions in a situation that was beyond her control: 1) She had to take on the “moral responsibility” that Cayetano García gave her, not only as a neighbor, but as a member of the municipal authority headed at the time by the political leader Erasto Pineda. This perspective reveals the subtle but imperious ways the upper social strata exercised, and continue to exert, power over people of the poorer classes as they seek the approval of those from their own social class, from the government, or in this case, from a foreigner, notwithstanding equally subtle actions of resistance, negotiation and consensus by subordinate groups that are worthy of their own analysis. 2) She had to fulfill the work that the sacred world assigned her as a means by which the mushrooms could speak and heal people. Refusing to do so would have implied divine punishment beyond what she had already experienced with the death of her relatives and the exhausting life she led, a modus vivendi in which violence had been historically normalized as an element inherent to human existence. Belonging to a different context from that of so-called “modern societies,” though no less violent, Maria Sabina was aiming to ensure her own and her family’s survival. Thus, getting rich from the commercialization of her shamanic knowledge was far from being the reason why she so often agreed to meet Wasson and other foreigners. The sacredness that she assigned from her own subjectivity to the veladas and the honguitos (“little mushrooms”) prevented her from treating them like the bundles of firewood she sold, the cigarettes she bought, or other things acquired so easily. It is thus ironic that, after her death, she herself was incorporated into the set of symbols that the “cultural tourism market” has used to continually reconfigure and strengthen itself.

In this way, María Sabina’s use of the Mazatec language goes beyond the act of merely speaking and communicating, making use of shamanic practices manifested in singing and poetry to achieve healing.

This leads us to another question: Was María Sabina really the one who spoke in the texts that she generated, and that are assumed until today to represent a reliable sample of her life and knowledge? This is extremely difficult to know because her diverse modes of speaking include constant evocations of a past determined by memory and not by the logic of modernity. In this way, María Sabina’s use of the Mazatec language goes beyond the act of merely speaking and communicating, making use of shamanic practices manifested in singing and poetry to achieve healing. Meanwhile, language itself has become part of the paraphernalia of ethnic identity that regional economic and political groups, supported in turn by state policies, have used to capitalize on Mazatec culture. Fernando Benítez (2006) was among the first to raise this point as he has tried to study the life of the “Mushroom Saint,” the greatest obstacle being the misunderstandings of symbolic language. Even though local interpreters were present in the many interviews that she gave, Benítez is of the opinion that they distorted “the meaning and originality of her story by passing it through the filter of another culture and another sensitivity” (p. 299). These errors have been repeated by both locals and foreigners as they attempt to understand the true meaning of this so-called ancestral knowledge.

How can we revive the memory of María Sabina without falling into the cliché image that the “sacred tourism market” has built around her?

By Way of Closing

How do we approach a discussion about sacred plants of the Mazatecs without falling into a descriptive and highly repetitive discourse? How can we revive the memory of María Sabina without falling into the cliché image that the “sacred tourism market” has built around her? More than stimulating conclusions, these queries should lead us to new questions about how to approach and construct a history that problematizes, rather than merely describes, the economic, political, and social processes experienced by the peoples of the Sierra Mazateca in their long process of integration into the nation-state. In this sense, the central function of memory is to question the dynamics of “modernity” in transforming Mazatec sacred symbols. María Sabina, like many of her contemporaries, exercised the act of memory in a distinctive way, since her life was influenced by notions of time that are very different from ideas about progress related to globalism and the Mexican state, such as are promoted by political and economic elites in the region. Moving beyond an idyllic construction of the past, it should be borne in mind that the history of the Mazatec people is a history of conflict, resistance, and negotiation.

Art by Karina Alvarez.

References

Benítez, F. (2006). Los hongos alucinantes [The hallucinogenic mushrooms]. Mexico City, Mexico: ERA.

Benítez, F. (2006). María Sabina y sus cantos chamánicos [María Sabina and her shamanic songs]. In C. Monsivais (Ed.), A ustedes les consta. Antología de la crónica en México [You know: Anthology of the chronicle in Mexico] (pp. 299–316). Mexico City, Mexico: ERA.

Glockner, J. & Soto, E. (2006). La realidad alterada. Drogas, enteógenos y cultura [The altered reality: Drugs, entheogens and culture]. Mexico City, Mexico: Debate.

Jacorzynski, W. & Rodríguez, María T. (Eds.). (2015). El encanto discreto de la modernidad [The discreet charm of modernity]. Mexico City, Mexico: Casa Chata, CIESAS.

Jelin, E. (2002). Los trabajos de la memoria [The work of memory]. Madrid, Spain: Siglo XXI.

Ricoeur, P. (2000). La memoria, la historia, el olvido [The memory, the history, the oblivion]. Mexico City, Mexico: FCE.

Rodríguez, C. (2017). Mazatecos, niños santos y güeros en Huautla de Jiménez, Oaxaca [Mazatecos, holy children and pale people in Huautla de Jiménez, Oaxaca]. Mexico City, Mexico: UNAM.

Rodríguez, C. (2019). Faena para el progreso. Huautla de Jiménez (Oaxaca) [Task for progress. Huautla de Jiménez (Oaxaca)]. Estudios mesoamericanos, 2, 47–57.

Tischler, S. (2010). La memoria ve hacia adelante. A propósito de Walter Benjamin y las nuevas rebeldías sociales [The memory looks forward: About Walter Benjamin and the new social rebellions]. Constelaciones. Revista de Teoría Crítica, 2, 38–60.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?