- Global History of Psychedelics: A Chacruna Series - October 4, 2023

- Can Psychedelics Promote Social Justice and Change the World? - August 30, 2021

- Kathleen Harrison: Wisdom, Endurance, and Hope – Reflections from a Psychedelic Woman - August 18, 2021

After a generous two-hour conversation with Kathleen Harrison, I felt inspired, blessed, and above all, I felt that I understood what it was like to be psychedelic. Kathleen is a teacher, a nurturer, a traveller, family member, an ethnobotanist, photographer, and a wise voice with important insights on how psychedelics help us to heal in this fraying world. Her life itself, has been psychedelic—she is a healing life force, connecting people, ideas, and plants, and stimulating new ways of seeing outside ourselves.

At one point she told me that she had never met a psychedelic she didn’t like. I was excited and nervous to learn more from this wise psychedelic traveler.

Coming of age in the 1960s, Kathleen arrived in San Francisco during the summer of love and recounted precious memories of mind expansion, music, and relationships that formed against this iconic backdrop of a psychedelic moment in time.

But, there is so much more to being psychedelic than Grateful Dead memories, or even anecdotes about her years of collaboration with Terence McKenna—years that included research, marriage, children, and publishing.

Kathleen explained that psychedelics have been critical teachers in her life, and, most importantly, because they opened her eyes to new ideas, reinforcing the need for investing in people and the kinds of values that come from interpersonal relationships. She described herself as being an anthropologist from a young age, always curious about people, their relationships, ancestors, customs, and interests. She fondly remembered traveling to Mexico as a young girl with her family and living along the coast, soaking up the atmosphere and learning about the people who lived there—not to study, just to live. This experience planted an important seed of curiosity that blossomed into a lifelong interest in people, plants, and the relationships among them.

Recordings are now available to watch here.

Today, in my academic world we are encouraged to do community-engaged research and to develop reciprocal relationships with our research subjects. Kathleen immediately sees through this window dressing and explained that true reciprocity is not something that is transactional. It is about deep relationships that evolve over time with mutual respect, making families and familial connections that extend over generations. This takes time. There is no roadmap for how to do it, you need to learn to listen, care, and it helps if you are empathetic.

This kind of insight and reflection comes from her lifelong interest in psychedelic plant medicines and the cultural knowledge about their use that emerged from studying people who live among psychedelic plants around the world. However, her work is also deeply focused on local contexts where she has created deep connections with specific families for over four generations. We can visit other places, but we need to be grounded and present in our own communities in order to fully appreciate how we interact in our ecosystems.

“We can visit other places, but we need to be grounded and present in our own communities in order to fully appreciate how we interact in our ecosystems.”

For Kathleen, studying psychedelics in this way is ultimately both frustrating and rewarding. Some of the people with psychedelic knowledge live in dire conditions—poverty, limited access to education, food shortages, barriers to owning property, etc.—factors that make it easy on the surface to recognize vast differences in resources and privilege. It is frustrating because one often feels helpless to shatter the bonds of poverty.

Yet, as she explained, in some Indigenous cultures in Mexico amongst the communities where she has worked and developed close relationships, the idea that someone could own psilocybin mushrooms or profit from them is wrong. She told me that one Indigenous elder explained to her that he knows the world needs this medicine. Considering that for some healers, they live in communities cut off from the internet or many outside influences, the recognition of our collective suffering is all the more poignant. The plant world is rich. It is diverse, magical, and despite economic conditions, some feel lucky to be rich in knowledge about these plant medicines.

In 1985, Kathleen initiated and co-founded Botanical Dimensions with her husband Terence. It functioned as a non-profit for 34 years, and is now functioning under a fiscal sponsor. Under Botanical Dimensions she carried out projects in Peru, Ecuador, Costa Rica, and California, with ongoing projects in Hawaii and Mexico. She is now working on a documentary film, Almost Visible, about the inter-familial friendship with a Mazatec healer’s clan. The private Hawaii Forest-Garden continues. The Ethnobotany Library is still in Northern California, but its survival into 2022 is in doubt, due to the inability to run educational programs under the pandemic, which is what supported it. Kathleen was the visionary and the energy behind Botanical Dimensions. Today, she continues that work by writing a book about the principles of living a psychedelic life.

I asked Kathleen then, does she see the psychedelic renaissance as an opportunity to face global challenges head on? To gain access to psychedelic plant medicines, and perhaps confront colonialism along the way?

Her answer surprised me, until I listened more and understood better.

She said no. In fact, she said that despite the shortcomings of the psychedelic movement in the 1960s and 1970s, that it was more hopeful.

Today, we have lost our critical edge, and above all, we are losing our critical thinking skills as a species.

Please donate to the Psychedelic Renaissance Documentary

I thought back to my training as a historian, watching the civil rights marches, the feminist campaigns, and Stonewall protests—all of which brandished banners of equality and collective action, in a mantra that together, “we shall overcome.” But, gazing at my 21st century reality, especially during this pandemic, we again see marches for Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, Truth and Reconciliation efforts to identify mass graves of children from Canadian Indian Residential Schools. These, along with daily news reminders of violence and discrimination that continues to reveal the ugly remnants of a broken system, one perhaps that will accelerate a need to look inward and focus on ourselves. But, surely, there has also been some progress? How could the 1970s have been better, when those same struggles persist today?

Kathleen summed it up in a word: hope. In the 1970s, she said, we had more hope. Today, we are saddled with many of the same injustices, while flooding and fires remind us that the earth itself is suffering. Our relationship between plants and humans is even further strained today than it was 50 years ago, or at least we are exposed to more and more images of suffering around the globe in our digitally connected modern lives. Yet, the exposure to more information has dulled our capacity to critically analyse that information, and our ability to reach around the world may have also diminished our willingness to think about our local circumstances and our responsibilities as a collective force for change.

” The goal… is not simply to decriminalize psychedelics, but to continue to nourish the relationship between plants and people that give psychedelics their meaning.”

We need to, she explained, each individually and collectively learn about the gift of plants, but also to be wise in our choices and be tuned into the collective suffering of others. In other words, we need collective action that is genuinely sensitive to the needs of others, and is grounded in our local realities. The goal, it seems, is not simply to decriminalize psychedelics, but to continue to nourish the relationship between plants and people that give psychedelics their meaning.

We need to slow down. Reflect. Pay attention. Be critical.

Our modern world has created a dizzying pace of information gathering and knowledge production—research goals and markers of success. But, what psychedelics can help to teach us is about the power of slow learning, or cumulative knowledge that takes time, and takes the form of prayer, song, appreciating the varieties of species, magic—a rich tapestry woven from different threads of knowledge. If we can learn to see all these threads at the same time, and marvel in their collective beauty as a whole, we might begin to appreciate the deeper knowledge that psychedelic plants have to offer. And, the fraying world needs us to reweave those threads by respecting the integrity of each individual thread while appreciating how woven together, they create something new. Something to hope for.

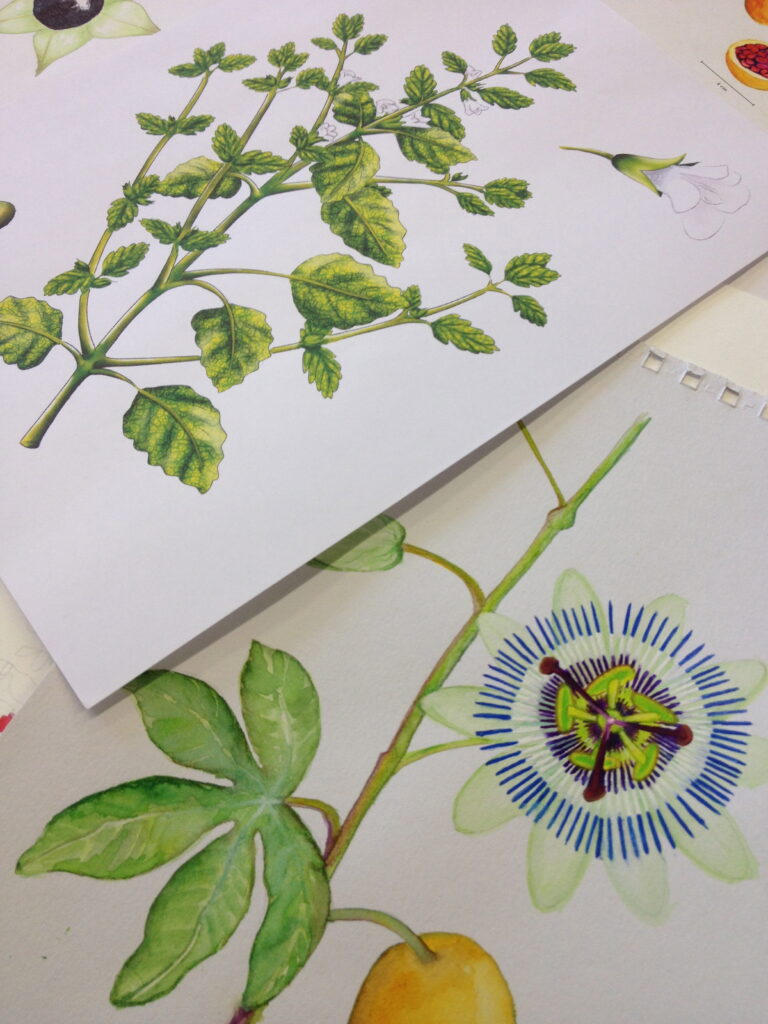

Feature Art by Luana Lourenço.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?