- Global History of Psychedelics: A Chacruna Series - October 4, 2023

- Can Psychedelics Promote Social Justice and Change the World? - August 30, 2021

- Kathleen Harrison: Wisdom, Endurance, and Hope – Reflections from a Psychedelic Woman - August 18, 2021

Stable. Clever. Loving. Creative. Supportive. Elegant. Strong. Caring. Intolerant of extreme weather.

These are some of the ways that Fee (Euphemia) and Julian Osmond described their mother, Jane, wife of Humphry Osmond. Jane was a nurse and a widow when she met Humphry during WWII at a hospital where he was working as a psychiatrist. Within a few years they married, and had a daughter, Helen. In less than two years after Helen was born, Humphry was offered a job in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, Canada—far from picturesque south shores of England where the two had grown up.

A New Home on the Wind-Swept Saskatchewan Prairie

The Osmonds moved to Canada in 1951. On the Canadian prairies, Humphry Osmond soon became the superintendent of the provincial mental hospital, described as the largest asylum in the British Commonwealth. It was here that he focused on research into hallucinations that led him to famously coin the word “psychedelic,” and where Jane had her own mescaline experience. While Humphry launched into a career studying psychedelics, Jane kept her own experience more private. Over the next decade Humphry encountered a colourful cast of researchers, politicians, and scientists eager to engage in psychedelic explorations. Jane meanwhile felt stuck in a windy, cold, even desolate agricultural community, starved of cosmopolitan features.

As Humphry’s career soared, Jane nonetheless provided consistent support. An excellent typist, a consummate host, a sophisticated source of intellect, and devoted reader herself, Jane had typed up Osmond’s now-pioneering studies in schizophrenia: “John Smythies and I were pushing poor Jane on the last draft of ‘Schizophrenia: A New Approach’ as she was doing the last bit of our packing” as they prepared to move to Canada, Humphry recalled. She brought stability to the home and support to Humphry’s budding ambitions to explore psychedelics. Helen’s childhood in Weyburn was an important focal point.

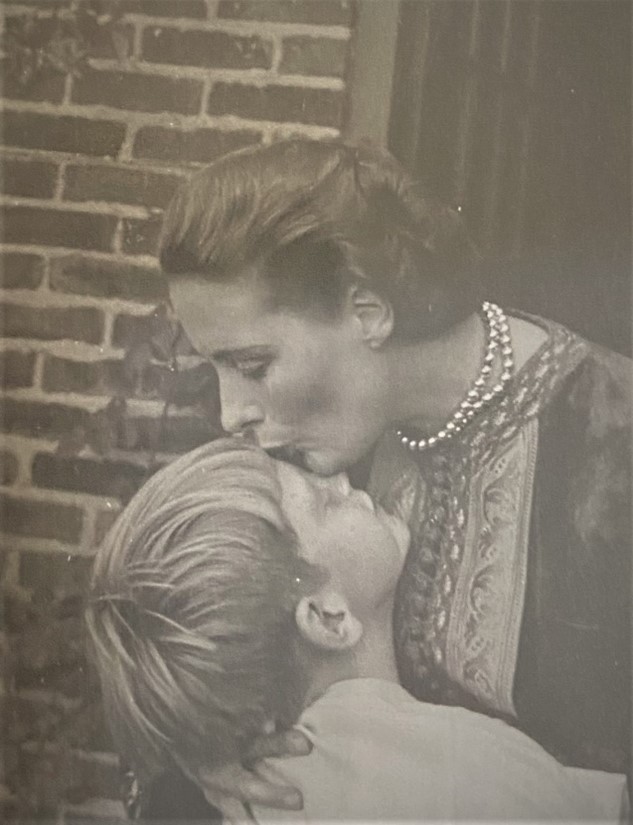

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Humphry described one such tender moment on April 23, 1954: “Here we are bereft on the prairie. Snow still on the ground and our little Helen far away in England, having left us about 42 hours ago. I have two parting pictures in my mind’s eye. An indomitable little figure dashing up the gangway to the plane determined that she and my sister should have a seat and disappearing into the flank of the silver brute. Then a little face pressed against the plane’s port with a Teddy Bear clutched close and waving the other hand briskly. Then the huge plane roared into the night leaving Jane and me weeping bitterly.”

Escape Through Travel

Sometimes Jane accompanied Humphry on trips to New York, Los Angeles, and of course, home to England. For Humphry Osmond, the “megapolis” of New York City was a bit intimidating, but Jane relished these opportunities to soak up the urban culture, replenish their library, and shop. Humphry sought advice from their good friend Aldous Huxley about frugal accommodations, leaving “enough money for visits to bargain basements which Jane is keen to see.” For Jane, thrift shopping brought its own hidden rewards. On one trip to New York City, Jane returned to Weyburn with a golden coat, and later sewed herself a dress to match. Humphry remarked to Aldous, that Jane and her elegant new coat would be the talk of Weyburn. Her son later recalled that people commented on her beauty, likening her to Katherine Hepburn and Deborah Kerr.

But shopping was merely a brief bit of entertainment. Jane accompanied Humphry to lectures and met with people who were curious about the psychedelic research world. Jane was there when Bill Wilson spent hours with them inquiring about LSD. She became friends with Matthew Huxley (Aldous and Maria’s son) and his wife Ellen, as they embarked on their own psychedelic experimentation under the Osmonds’ watchful eyes. Jane and Helen had their own adventures with Al and Rita Hubbard when they escaped Saskatchewan for visits to an island in British Columbia. Humphry Osmond records that Al had given mescaline to Jane, unfortunately, nothing further is said about Jane’s experience.

Community Engagement

While Jane may have relished these brief escapes from the wind-swept prairies, local women in Weyburn remember coveting her influence in their community. Friends and nurses at the Provincial Mental Hospital recalled Jane’s generosity and erudition. She hosted teas and dinners, inviting staff and families from the hospital who were permitted a glimpse into their lives, and a sample of their record collection. For some of these invitees, Jane was a model of elegance and culture and they looked forward to these dinner parties. She befriended Amy Izumi, wife of architect Kiyoshi Izumi who recommended redesigning hospital spaces after experiencing LSD. In 1959 Jane gave birth to Euphemia (Fee). Amy Izumi was named one of her godmothers. Jane later gifted her maternity clothes to one of the wives of a local psychologist, who recalled treasuring these clothes—the most most beautiful and stylish maternity wear in the region.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

The Osmond household must have been quite the standout in the small community; undisputed master of the domestic sphere, Humphry often notes Jane’s various home beautification projects, often carried out when he was away. When he was home, her concerns may have been drawn elsewhere. Humphry was an adventurous “kitchen chemist” and on at least one occasion he felt close to death after consuming a homemade concoction. Writing to Aldous after the fact he notes: “I very prudently did not call Jane (this was from midnight to 04:30) because I feared anxious colleagues might give me morphine or something and kill me… I only dared tell Jane the other night!”

“Too Good a Caregiver”

Jane seems to have made friends easily and made caring seem natural. Her nursing training combined with her sense of duty made Jane a constant source of strength for those around her. When Maria Huxley succumbed to a cancer diagnosis Humphry wrote to Aldous suggesting that Jane could come to help Maria. This pattern of caring for others, perhaps at times at her own expense, seems to be lifelong; both Fee and Julian remember her often taking responsibility for the wellbeing of those around her.

“Her nursing training combined with her sense of duty made Jane a constant source of strength for those around her.”

As Aldous’ first wife Maria’s health rapidly declined in early 1955, Humphry Osmond writes: “I am naturally very sad to hear that Maria is not well. Jane and I have discussed the matter and if you would be agreeable she would be glad to come down to look after Maria until it is clear how things are going. Jane has done a great deal of nursing. It might be nicer for Maria than having someone to whom she would have to adjust. I would be glad to know that Maria had someone near her whose kindness and competence is proven… we love you both very much.”

Before Jane and Helen could come to California Maria’s conditioned worsened and she had her last psychedelic experience on her deathbed. Aldous later wrote to Humphry Osmond: “I think you know how deep was her affection for you. She always regretted that she had not had the opportunity of getting to know Jane better.”

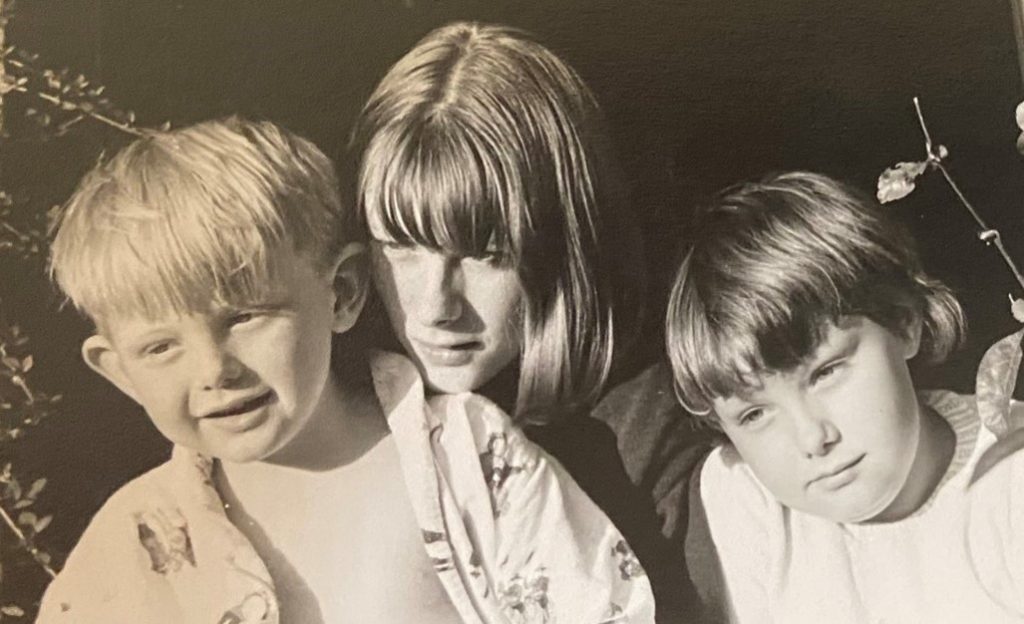

In 1961, Humphry Osmond left his position in Saskatchewan and the family returned to England where their son, Julian, was born that same year. Jane was once again in south England, surrounded by extended family and more familiar surroundings. But Humphry was not one to sit still and he was soon invited to a new post in the United States. In 1963 he took the position of director at the Bureau of Research in Neurology and Psychiatry at the Psychiatric Institute in Princeton, New Jersey. With a teenager and two young children, Jane decided to remain in England with a more extensive network of friends and family close by.

For the next fifteen years, Jane and Humphry maintained a long-distance relationship at a time when letter writing was the most cost-effective form of communication. Fee and Julian still remember the sound of her typewriter most evenings, as Jane and Humphry wrote to each other daily, and enjoyed bi-annual visits.

Humphry and Jane had an incredible network of friends who stopped by for visits. During this period Fee and Julian were busy with their studies, Fee a “day girl” recalls their daily drives to and from school, while Julian attended boarding school, where he recalls his mother writing to him and visiting weekly. Jane and the children continued to host a long list of intrepid travelers and friends who would come by their home, sometimes unannounced. Fee recalls her godmother, Eileen Garrett driving up their county lane in her Rolls Royce, and arriving with glowing red nails and matching lipstick. Julien recalls visiting god-mother Garrett at her French villa and being enchanted by the stuffed tomatoes, strawberry tarts, coke in a bottle, and the wonderful visits by the pool side. Sir Julian Huxley visited their home in England, after becoming close with Jane and Humphry. Young Julian Osmond was named after Aldous’ brother, Julian, and his visit left an impression on the young boy: “he was very tall and thin”; to which Fee helpfully corrects “Aldous—tall & slim. Julian—not so much!” With family friends that included psychic mediums, knighted biologists, CIA operatives, alongside a host of researchers, writers, and politicians, Jane often felt pressured to ready the house for guests and engage in meaningful conversation. Unexpected guests could be a cause for irritation, but Jane would always make guests feel welcome and wanted.

Support the Eagle and the Condor’s Ayahuasca Religious Freedom Initiative

“Jane Sends Love”

But, Fee and Julian have fond memories of quieter moments with their mother, who also seemed to relish more simple pleasures: family picnics, long walks, reading, and flying kites on the South Downs. They remember their mother as the very backbone of the family, nourishing the children and sustaining a relationship with Humphry across the Atlantic. Brighton was another favourite spot, and Jane would take the kids on day trips where they would fly kites by the sea. The time spent in far-away Saskatchewan would arise occasionally, and Fee and Julian were aware of “Dad’s word”—psychedelic—which might be said on the radio from time to time. Long walks in nature were common, Jane loved the natural beauty of Surrey and especially in nearby South Downs, where her ashes were later scattered after her death in 2010.

In 1975, Humphry Osmond left for Tuscaloosa, Alabama, to become the superintendent of the Bryce Hospital, another large psychiatric institution. This time, after more than a decade of letters, phone calls, and holiday visits, Jane, Fee, and Julian boarded a ship and made a journey across the ocean to join Humphry in Alabama. Helen, now an adult, remained in England and followed in her mother’s footsteps, taking up nursing. Once more, leaving the rolling hills and ocean breezes behind them, Jane arrived in Tuscaloosa to the blazing heat and stench of a pulp and paper mill. Jane was not impressed with the heat, which seemed to have replaced the frigid cold of the Canadian prairies, and the damp of England. By this time, Humphry’s work with psychedelics had changed too.

While in Saskatchewan, psychedelic science was in its ascendency, but by the mid-1970s that work was tarnished by claims of it being unethical, risky, or even damaging. Humphry’s focus shifted once again back to his patients with schizophrenia, and less on the potential for psychedelics to bring insights or relief in this field. His children recall knowing that “Dad had invented a word,” but the specter of psychedelics was very different by the time they entered high school in the mid 1970s, and perhaps like typical teenagers, the comings and goings of their parents were not of particular interest.

Ever the caregiver, Jane resumed her position in the family home after more than a decade of living a part. It seems that both partners had developed their own patterns of coping in the intervening years. Fee and Julian remember Jane reading, sewing, taking long walks, and resuming her work with “Dad” as a sounding board, typist, and listener. She also worked part time at an Emporium selling antiques and fine collectables. Humphry had a real appetite for linking people and ideas, and his children remember him sitting in his living room chair, talking to Jane, or quietly reading. They vividly recall him constantly scribbling notes and cutting clippings out of newspapers and magazines to attach to letters to his friends and colleagues, often with a scattering of them at his feet—dad’s “memos”—much like the crumbs of toast he’d leave in the kitchen, to Jane’s perennial bane.

“As we enter into another psychedelic moment in history, we are grateful for… the care that Jane took to nurture relationships, record meetings, and nourish a network of thinkers who helped to lay foundations for a psychedelic science.”

As we enter into another psychedelic moment in history, we are grateful for those clippings, and for the care that Jane took to nurture relationships, record meetings, and nourish a network of thinkers who helped to lay foundations for a psychedelic science. Humphry’s letters to Aldous routinely ended with “Jane sends love.” Indeed, Jane’s support is a reminder to all of us that we should acknowledge the people in our lives who encourage us to promote radical ideas. Fee suggests that, “without her, Dad would not have had the freedom to do all that he did.”

With thanks to Fee Blackburn and Julian Osmond for generously sharing their thoughts of their mother with us.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?