- Is Ayahuasca Possibly Less than Five Hundred Years Old? - June 18, 2020

- Urgent Action Needed: COVID-19 Pandemic Devastating Amazonia - May 15, 2020

- Humankind Crowned – Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Virus - April 2, 2020

It makes a difference, indeed, whether we report to the public that we are investigating a hallucinogenic drug that was spread relatively recently through Catholic missions and rubber camps, or whether we report that we are working with a traditional remedy that has been used by forest Indians for at least five thousand years.

Much has been speculated about the origin and the actual age of ayahuasca. Some scholars attribute thousands of years to this brew, while others, including me, assume a much more recent discovery of ayahuasca. Up front, I wish to underline that origin stories seldom tell us what actually happened in the past—shrouded in the fog of time— but they reveal much about the people who talk about it in the present. It makes a difference, indeed, whether we report to the public that we are investigating a hallucinogenic drug that was spread relatively recently through Catholic missions and rubber camps, or whether we report that we are working with a traditional remedy that has been used by forest Indians for at least five thousand years. Plus, I perceive it much more rewarding to “enable” indigenous people to discover an important new item in colonial times, and therefore to get rid of a popular image of “traditional” indigenous people who are only “reproducing” what had been discovered by mythical forefathers in ancient times.

During the evolution of modern anthropology and ethnology in the nineteenth century, most researchers believed, in line with their era’s common sense, that whatever so-called Naturvölker. or “primitive peoples.” performed was conserved from the Stone Age. Thus, in nineteenth-century ethnology, the importance of “old knowledge” in indigenous societies was defined circularly under the assumption that indigenous knowledge would be “old.” Such attitudes often prevail.

Following this vein, Jeremy Narby (1998, p. 154) wrote about “ayahuasca-based shamanism … indigenous people of Western Amazonia … have practiced without interruption for at least five thousand years,” referring to Plutarco Naranjo’s “archaeological evidence.” Peter Gow (1994, p. 91), on the other hand, “believe(s) this approach is false historically and ethnographically.” So, let us first look at Naranjo’s and others’ archaeological record.

What is Still Not Revealed by Archaeology

Naranjo’s argument is, simply, logically false: Although he correctly shows that Ecuadorian lowland populations produced small ceramic vessels at least since 2.400 BC, that is, before they knew about liquor distillation, he falsely concludes that, because of today’s people serving ayahuasca (or liquor) in small ornamented glasses or cups, the presence of ancient adorned cups would be evidence of the ancient use of ayahuasca (Naranjo 1986, p. 121).

For this specimen, I even believe that the plants were not “used” at all, in the sense of ingestion, but placed together in this burial site as offerings, or for the afterlife.

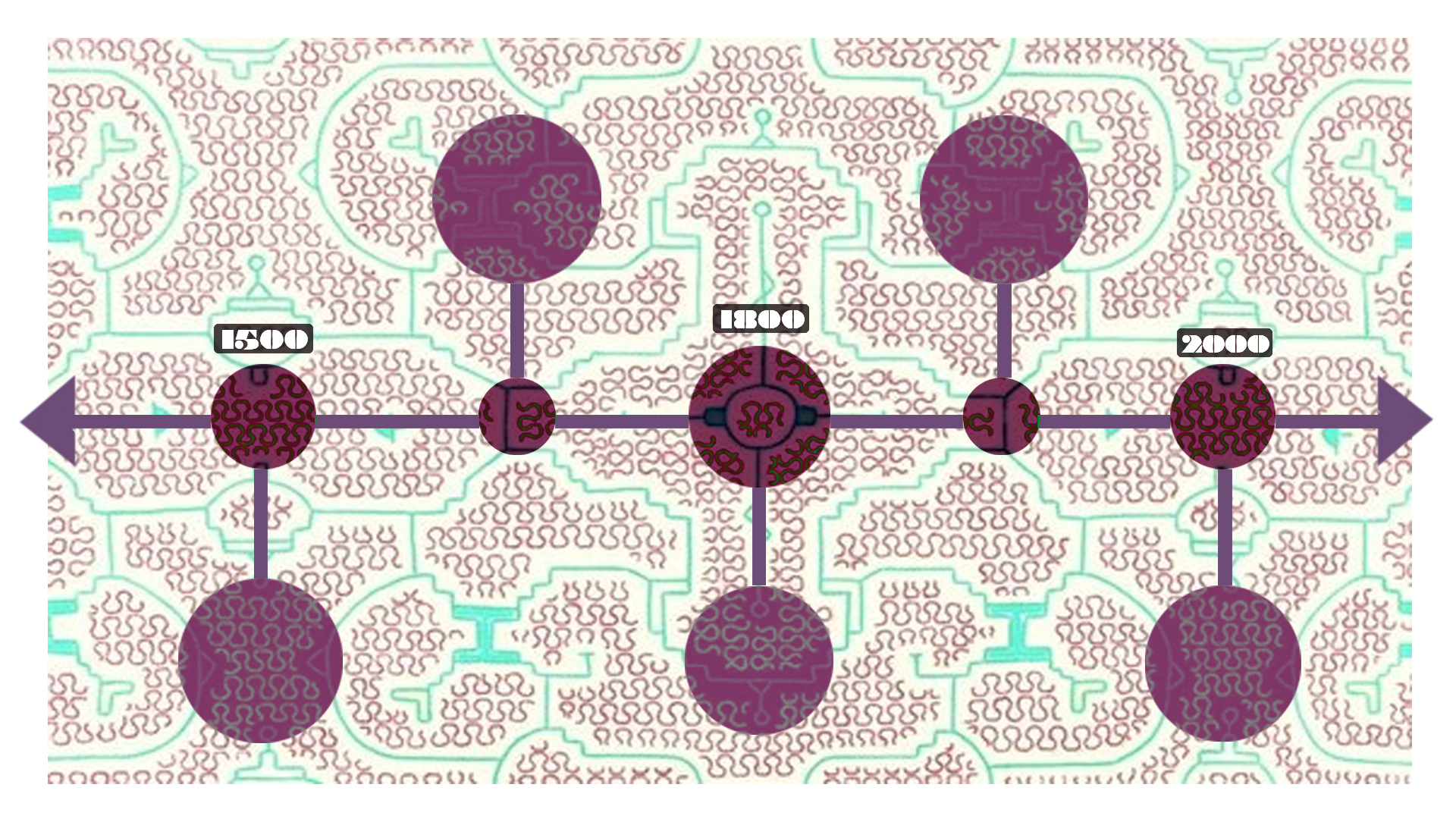

More recently, Ogalde et al. (2008) provide evidence of harmine in ancient Chilean mummies’ hair, which the authors themselves interpret as an evidence of the ingestion of Banisteriopsis and, finally, of ayahuasca, by these people. This “evidence” was already debunked by Giorgio Samorini in an article published on this site. Miller & al.1 analyzed remains from a Bolivian burial site dated back to ca. 1.000 AD and suggest that “Although our results do not provide conclusive evidence for the early use of ayahuasca … (as an entheogen using Banisteriopsis and Psychotria together), it is evidence that this combination was possibly used as early as 1,000 y ago.” This possibility is, however, rather improbable. Together with Samorini (2020, private communication), I tried to make sense of this little pouch that presumably contained plant material with five alkaloids (bufotenine, DMT, cocaine, harmine, and, potentially, psilocin); this is called a “ritual bundle” by the archaeologists—although, of course, its “ritual” significance is a priori attributed by the researchers—who later concede that “the plants containing these psychotropic compounds may have also been used separately, potentially even as medications.” For this specimen, I even believe that the plants were not “used” at all, in the sense of ingestion, but placed together in this burial site as offerings, or for the afterlife. This is because, if the pouch really held harmine- and DMT-containing plant material, it was far too little for even one individual dose of any form of ayahuasca. With all that, archaeological data is still thin and highly speculative. Let us therefore turn to historical and ethnographic data about past ayahuasca use. All historical mentions are from the eighteenth century or newer (see Samorini,2 3 Torres,4.

Shipibo-Konibo and Their Teachers

First, the legendary, most powerful healer persona, the meraya, was always depicted as somebody reaching the most remote regions of the cosmos without using ayahuasca.

During my work with Shipibo-Konibo healers, I was repeatedly confronted with some problems that did not fit into the picture of a millennial ayahuasca tradition. First, the legendary, most powerful healer persona, the meraya, was always depicted as somebody reaching the most remote regions of the cosmos without using ayahuasca. Second, Shipibo narratives of the origin of ayahuasca often mention Kukama names and places; the Kukama live north, that is, downriver of the Shipibo, and were among the first populations to be held in missionary reducciones (Indian resettlement villages). Many Shipibo healers mentioned Kukama names for their teachers.

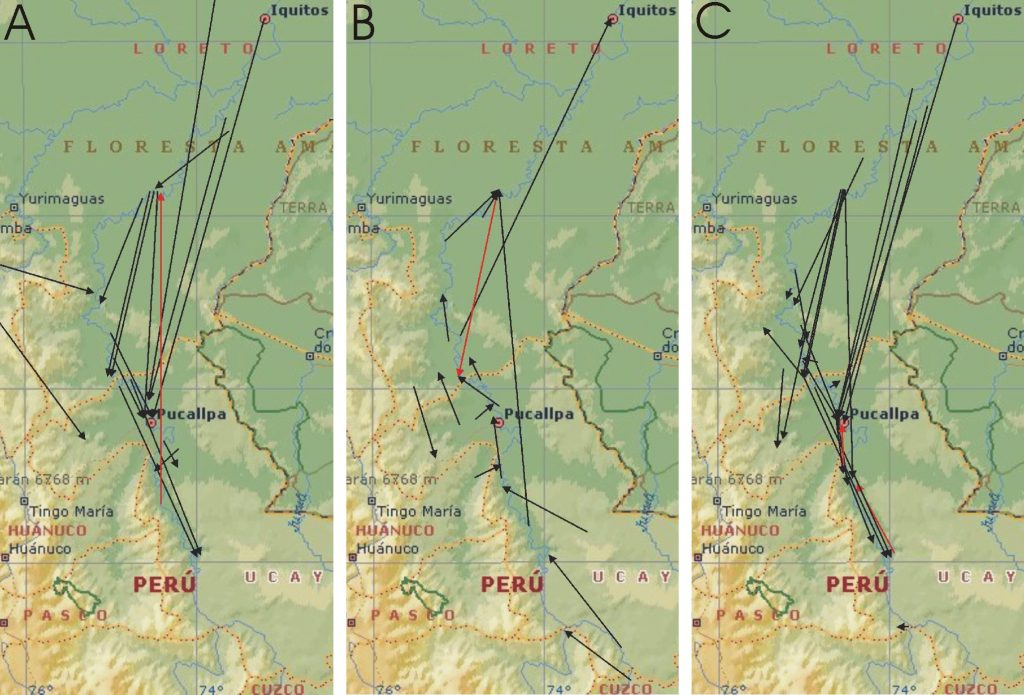

A survey of recent individual migrations of ayahuasqueros in the Ucayali valley reveals that, almost without exception, the teachers came from downriver, and the students traveled towards the bigger settlements to meet them. After having learned how to use ayahuasca, the students traveled upriver again, or returned to more remote places where they carry out their practices. I have never heard of any renowned ayahuasquero on the Ucayali river who had been instructed by someone from upriver, say, from the south, or from more remote areas.

These facts alone seem sufficiently convincing to draw a picture in which ayahuasca had traveled from northwest of Iquitos via Lamas and the Cushabatay passage, up the Ucayali river, and then reached the bigger groups in the south. In the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, it then crossed the Brazilian frontier into Acre, where Indians and seringueiros started to use the brew, before the Santo Daime church was founded in 1930. Groups that then remained isolated came in touch with ayahuasca only recently; that is, after their (renewed) contact to riverine societies.

For example, the so-called “Remo” populations were in contact with the riverine Shipibo and predecessors in the eighteenth century. However, despite a potentially decade-long contact between Shipibo and “Remos,” by 1790, today’s “Remos,” the Iskonawa, had never heard of ayahuasca in 1959. Similarly, the Kakataibo people, whose predecessors probably lived on the Ucayali river together with Shipibo, retreated into the woodlands around 1790, and just then developed as a “separate ethnic group.” If the Shipibo people at the reducciones of Manoa (Río Cushabatay) and Sarayacu had used ayahuasca for generations, then it would seem very strange if their one‑time close relatives, the “Remos” and Kakataibo, fleeing into the woods, had both completely abandoned its use and forgotten about it, not even referenced in myths. With that, probability is very low that, in 1790, ayahuasca use was widely known in the Ucayali valley.

Terminology and Singing Styles

In ayahuasca-related etymology, we can isolate one tendency: many terms that are known in the Peruvian south are rooted in the north, and none used in the north come from the south.

My main argument is based on etymology and musicology but, in this summary, I can only hint at it. In ayahuasca-related etymology, we can isolate one tendency: many terms that are known in the Peruvian south are rooted in the north, and none used in the north come from the south. The predominance of Kichwa and, to a certain extent, Tupí/Kukama points towards two movements in the course of which these languages have been carried from the north to the south: the Jesuit expansion and the rubber boom.

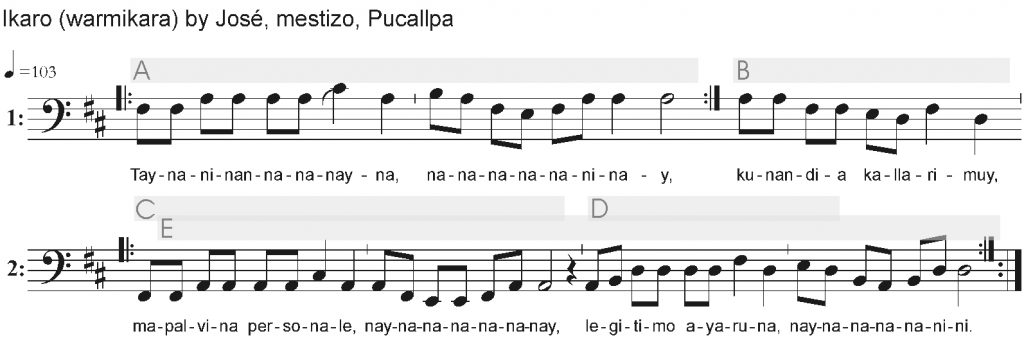

To provide but one example, consider the term ikaro (icaro, icara, icarar, etc.). The term means “song” any kind of festive, or private, or even children’s song—in Kukama language, with ikarutsu meaning “to sing,” again, any kind of song. South of the Kukama, the term is used by all those people using ayahuasca specifically for a song genre only used in medicine context with a specific musical form reminiscent of Kukama singing style (again, among the Kukama, of any kind of song). This is a strong indicator that ikaro, together with ayahuasca, was brought to the peoples of the south via the Kukama after ethnogenesis occurred (that is, after the “ethnic groups” as we know them today were formed and occupied “their territories,” as mentioned above, for the “Remos” and Kakataibo): after the eighteenth, and further south, the nineteenth centuries.

Furthermore, the musical structure of the ayahuasca-related ikaro is the only song structure compellingly similar between the Río Napo and the Río Urubamba. If ayahuasca would be in use for centuries, or even millennia, among the groups south of Iquitos, as it is often assumed, or these groups even discovered the principle of ayahuasca independently (as is suggested by some authors and practitioners), it would appear rather illogical that the music especially connected to ayahuasca sessions would be the only music fairly similar among all the groups.

Towards a More Modest View on Ayahuasca

We thus arrived at a number of indications that point towards a rather recent distribution of ayahuasca use in the southwestern Amazon. In their totality, these indications suggest a clear tendency, as outlined above, the bulk of data constituting circumstantial evidence. Retracing the way the combined, hallucinogenic ayahuasca or yagé spread in post-Columbian times, it seems that it was originally discovered around the Napo and Putumayo rivers, possibly by western Tukanoan-speaking groups or their predecessors. It is, however, still premature to precisely respond to the big question: When did this happen? It is also true for this region that we totally lack any corresponding observations by missionaries or explorers before the eighteenth century. Therefore, I think that the assumption of millennial use cannot be held, simply because it would be rather illogical, in my understanding, if people in one small region would use a cultural item for thousands of years, unnoticed by other indigenous groups, who, in pre-Columbian times, exchanged many other cultural items intensively (for example, via Tupían and Arawakan networks, see Hornborg & Hill5).

For example, according to my personal observations in two decades of fieldwork in the region, the vast majority of Shipibo-Konibo individuals are not into ayahuasca commerce and do not agree with the “ayahuasca-shaman” identity concept that has been collectively imposed on them.

I would also like to highlight two ethical issues that are, however vaguely, connected to the question of the age of ayahuasca use: First, in ayahuasca tourism and exoticism, many times, a simplistic view is imposed on the indigenous people, as if they all have been traditional ayahuasca shamans since ancient times. The ecological and socio-economic consequences in western Amazonia caused by such an overestimation of ayahuasca are generally overlooked. For example, according to my personal observations in two decades of fieldwork in the region, the vast majority of Shipibo-Konibo individuals are not into ayahuasca commerce and do not agree with the “ayahuasca-shaman” identity concept that has been collectively imposed on them.

In many places it seems that, without providing alternative facilities to care for the sick, commercial use of ayahuasca is substituting the former system of pragmatic curing; a system that was preserved, developed, and kept self-reproducing, despite epidemics, conquest, missionary conditioning, and rubber slavery.

Second, there is an urgent problem in healthcare: Many healers are shifting their main occupation from curing local patients to providing spectacular experiences for visitors from the West. Therefore, many indigenous and mestizo families are nowadays trapped in a vacuum of medical care. In many places it seems that, without providing alternative facilities to care for the sick, commercial use of ayahuasca is substituting the former system of pragmatic curing; a system that was preserved, developed, and kept self-reproducing, despite epidemics, conquest, missionary conditioning, and rubber slavery.

I hope to have contributed to a more modest view on the ayahuasca phenomenon. Ayahuasca usage, both in a western Amazonian setting and in Western society, has its powers and offers certain possibilities. However, getting rid of romantic images (like “traditions preserved from the Stone Age”) and analyzing the role of ayahuasca in indigenous history and identity in a more critical way, can be very helpful to actually concentrate on the present use—or notions of misuse—of ayahuasca, in academic and popular discourse, as well as in ayahuasca-related trials. In the long term, I think, there is no practical reward to be expected from romanticizing and obscuring the provenance, history, and consequences of ayahuasca use. Presenting arguments that are carefully built upon historical or ethnographical data is more effective than taking for granted poorly evidenced millennial traditions.

Art by Mariom Luna.

—

Note:

This essay is a slightly updated summary of a book chapter I published in 2011 (see here or here). Only newer literature not cited in the original paper is added to the reference list. For the whole argument and the complete list, please consult the original paper.

References

- Miller, M. J. (2019). Chemical evidence for the use of multiple psychotropic plants in a 1,000-year-old ritual bundle from South America. PNAS, 116(23), 11207–11212. ↩

- Samorini G. (2014). Aspectos y problemas de la arqueología de las drogas sudamericanas (Aspects and problems of the archeology of South American drugs). Revista Cultura y Droga, 19(21), 13–34. ↩

- Samorini, G. (2019). The oldest archeological data evidencing the relationship of Homo sapiens with psychoactive plants: A worldwide overview. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 3(2), 1–18. ↩

- Torres, C. M. (2018). The origins of the ayahuasca/yagé concept: An inquiry into the synergy between dimethyltryptamine and beta-carbolines. In S. M. Fitzpatrick(Ed.), Ancient psychoactive substances (pp. 234–264). Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ↩

- Hornborg, Alf, & Hill, Jonathan (Eds.) (2011). Ethnicity in ancient Amazonia. Reconstructing past identities from archaeology, lingustics, and ethnohistory. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado. ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?