- Educating Gringos in Shipibo Ways - December 13, 2021

- LSD in the House, Cops at the Door: A Psycholytic Therapist Reflects on Her Darkest Moment - July 28, 2021

- Peer support line helped 16 “bad trippers” avoid the emergency room - June 4, 2021

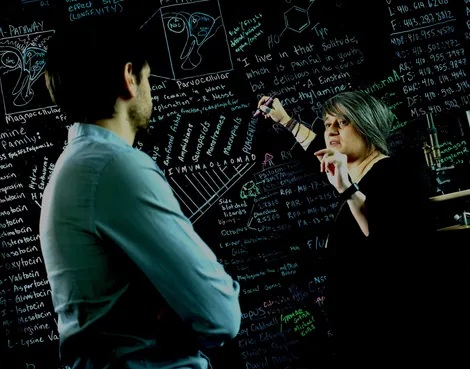

Gül Dölen is a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins whose work-life focuses on the details of receptors and signaling and oxytocin. But Gül is no lab rat. Call her for a videochat, and one day she’s in a garden, surrounded by purple flowers and a friend’s chattering kids who pop up and say hi. The next video call, Gül—pronounced gool, not gull—is down in the dumps after a friend’s cancer diagnosis.

Makes sense. One of Gül’s areas of study is connection at the molecular level—how neurons and neurotransmitters help animals be social. Animals like, you know, little kids in gardens.

With a few recent papers, Gül Dolen has lit up the science of MDMA, and shown how it can help us connect in new ways. She used MDMA to get octopuses to snuggle. She used MDMA to teach old mice new tricks. And now Gül may be on the verge of some of the biggest discoveries in psychedelic history, which are being used to test new treatments for autism, stroke, and language deficits.

But you probably haven’t heard of Gül, and you’ve almost certainly never heard of her new theory of how psychedelics work. And one reason might be: because she’s a woman.

“Sexism is real. I challenge any man who is certain there is no sexism in science to submit their next grant proposal under a name that is assumed to be feminine.”

Gül Dölen

“When I started in neuroscience, I sort of imagined we were living in a post-sexist world,” Gül says. But “sexism is real. I challenge any man who is certain there is no sexism in science to submit their next grant proposal under a name that is assumed to be feminine.”

This sexism has real consequences. For one, it almost stopped Gül from getting out some ideas that are changing the face of medicine.

“I was pushed to the edge where I thought about leaving science,” Gül says.

Gül’s Critical Period

Gül was born to be a scientist. She has a big family of PhDs, MDs, and other intellectual high-achievers. Both parents were physicians, and Gül saw sexism then: when people called the house and asked her mom to pass the phone to Dr. Dölen, some were surprised when she said, “I’m Dr. Dölen, too.”

Being successful in science was how you fit in as a Dölen. She earned an MD and PhD from Brown and MIT. Published papers in top-ranked journals. And, finally, she got her own lab at Johns Hopkins, which is the scientific equivalent of becoming a coach in the NBA or a fighter pilot in the Navy.

But lots of high-flying professions are still “A Man’s World,” and psychedelic neuroscience is no exception.

Gül felt diminished regularly when her senior male colleagues nodded at her ideas politely or dismissed them outright, when men “mansplained” to her, she says, “schooling me on technical details of things that I had actually pioneered.” Gül watched male colleagues at the same stage in their career get more grant money, more easily. Why? Gül thinks some men who run funding organizations view women as “spoiled children or indulgent wives who are being given an allowance rather than as adults.”

Her lowest point came in August of 2018—she still remembers the date. She had just been awarded nearly a million dollars by a private foundation to study autism. It was a huge win. Roughly three years of funding, including salaries for people in her lab. Then, unexpectedly, the foundation revoked the grant. Took all that money back.

Gül was sitting in a meeting when she got the news. It felt like a gut punch. A friend said it looked like she had died. The foundation claimed the decision was about funding levels. But a friend inside the organization, Gül says, echoed Gül’s suspicion that sexism played a role, that a foundation official said a million dollars was “too much money for her.” Gül is convinced that that much money was only too much money for her, that it wouldn’t have been too much money for him—whoever he might be. “People can say there must be some other explanation, and that this is just sour grapes,” Gül says. “No. This was not about any of the reasons they gave, but sexism.”

In Gül’s experience, psychedelic neuroscience welcomes women, but there are still limitations. Labs seek out female undergrads and post-docs—but are wary of women leaders. Being a woman in science, she says, is like climbing a mountain in an ice storm while men do it on a sunny day.

After that, Gül thought about quitting. Maybe go work in a women’s shelter, or start up a psychedelic clinic or go back to school to become a psychedelic psychotherapist.

But, then, two or three weeks after she lost that grant, her world changed. All because of a study that was partly just for fun.

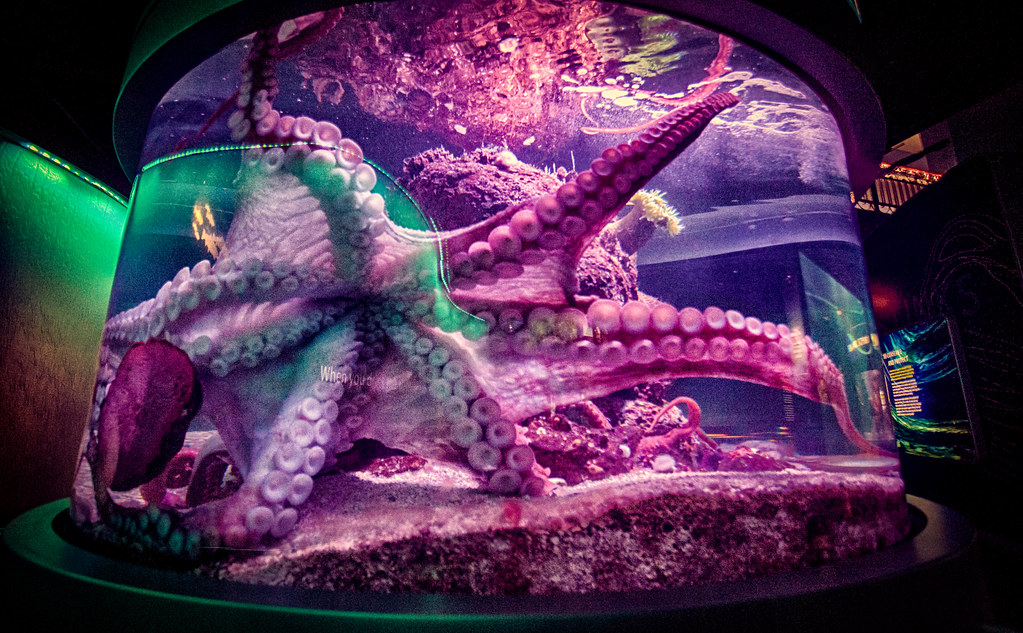

How Octopuses Roll

Gül: “Up until our experiment, nobody had given MDMA to any animal other than a mammal. Octopus brains are totally different from ours. They’re organized differently. Banana slugs and flies and worms, all these invertebrates, our last common ancestor was over five hundred and fifty million years ago. The dinosaurs have come and gone in the interim between when we and octopuses had our last common ancestor. And so there was a pretty good chance nothing was going to happen.”

But that’s not what happened. The octopuses started to cuddle and hug each other. Which was remarkable. They were dancing, and sort of playing and doing back flips. Their whole demeanor changed.

Gül’s Paper Went Viral

Gül’s octopus paper went viral. It made the scientific circuits but also appeared in tabloids and newspapers like the New York Post and Rooster Magazine and Instagram feeds. It’s sharable because it’s fascinating on many levels.

Lesson One: X is Awesome for Everyone

At the level of the Facebook share, the takeaway was: “Scientists gave octopuses ecstasy! What kooks! And those eight-armed bastards cuddle puddle just like we do! Let’s score some molly and get tentacly!”

Lesson Two: Love is Old

At the NPR level, the message was that connection is ancient. A recent survey found that psychedelic science papers almost never use the word love. Gül’s papers don’t use the word. But I’ll say it. With the octopus paper, Gül found a new, fascinating, hard-science way to address the question of, What in our mushy brains and bodies lets us stare into the eyes of another and become, as Keats said, “two souls but with a single thought”? Gül showed that love—some form of love—exists in octopuses (and probably sea slugs and banana worms too). Sociality is 500 million years old, at least.

Lesson Three: We May Be Talking About the Way Psychedelics Work All Wrong

At the deepest, most complicated level, the octopus paper proved something intellectual but important about psychedelics: the common story of how psychedelics work may be incomplete.

Nowadays, when scientists look at why psychedelics work in the human brain, they use brain imaging studies to identify regions that are activated or dampened during psychedelic experiences. They then tell stories about what happens in, say, the parietal lobe or the nucleus accumbens.

I know I do this. When I talk about how MDMA works and I want to sound smart, I say MDMA quiets down the amygdala or the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain involved in emotional responses such as fear and cognition.

Gül explains to me that this is not wrong, exactly. MDMA does do those things in humans. But octopuses don’t have an amygdala or prefrontal cortex. And since octopuses apparently “roll” just like ravers do, MDMA must do at least some of its work at the level of molecules. So referring to components of the brain’s structure, such as the “amygdala” or “default mode network,” might not be the best or most accurate—let alone only—way to describe how psychedelics work.

Gül’s Redemption

Gül was still reeling from losing that nearly-million-dollar grant when she went to give a talk at a conference. As she was talking, and as the Internet really vibrated with her lab’s One Weird Octopus Trick, she says her voice changed. She says she felt “like the Phoenix rising from the ashes, starting to get my feet under me again and say bold things.” She ended her talk with a bit about how damaging sexism in science can be.

The Old Mice Who Learn to Connect Again

Less than a year after wanting to quit, Gül published a paper in Nature, one of the biggest scientific journals.

The adage “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks” captures a certain truth about the brain, Gül says. It had long been assumed that the brain was “hardwired”—the connections between neurons have become fundamentally and irrevocably established—by the time you reach adulthood, and certain skills become impossible to learn. There are good reasons to believe this. Americans can’t hear the tones of the Chinese language. Neglected babies in Romanian orphanages never fully learn to form social connections.

In neuroscientific language, the “critical period” during brain development, generally in infancy and early childhood, has closed in adults.

Gül’s paper was called “Oxytocin-dependent reopening of a social reward learning critical period with MDMA.” It showed adult mice return to a child-like state of openness to connecting to other mice, if they’re given MDMA (but not if they’re given cocaine). In getting old mice to bond together as if they were children, Gül and her team were in fact able to teach old mice new tricks. And Gül proved the brain’s of mice had reopened into a kind of “critical period” while on MDMA.

Researchers of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD knew the drug opened people back up to social connections. Gül explained why at the level of molecules.

“It was pretty groundbreaking,” says Fred Barrett, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins. “You can jump in your car and push the gas pedal and it will go. But if you understand what’s under the hood, you can build a better car,” Barrett says.

A New Answer

Gül has helped change the way we understand how psychedelics work.

“It doesn’t have to do with my default mode network or my amygdala,” Gül says. “What I say is, psychedelics reopen critical periods, they make an old brain young again, they allow you to go back to that state where you’re receptive to the world like a child.”

“Psychedelics reopen critical periods, they make an old brain young again, they allow you to go back to that state where you’re receptive to the world like a child.”

Gül Dölen

And this “critical period” theory makes some sense, doesn’t it? Psychedelics do feel like you’ve become a child again. You stare at flowers or your siblings the way a baby might, as though the world still had the spit shine of creation still on them. And, on psychedelics, you can reorient your relationship to that world, learn to connect in a new way, like a baby.

And new experiences, or new perspectives on familiar experiences, enables the brain to form new neuronal connections.

How the ‘Critical Period’ Theory Expands the Playing Field

If “critical period” is the framework, rather than “quiets the amygdala,” that’s a conceptual change in what we think psychedelics are capable of.

There’s only so much you can do with a quiet amygdala. And we’ve grown used to the idea that MDMA treats mental illnesses. We now have the famous phrases, repeated like mantras by the psychedelic community.

“MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD.”

“MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for anorexia.”

Each phrase has three components. Watch the pattern:

MDMA. Psychotherapy. PTSD.

MDMA. Psychotherapy. Anorexia.

Psychedelic drug. Psychotherapy. Mental illness.

This pattern boxes MDMA into a corner: a drug used in psychotherapy to treat mental illness. But if you love MDMA, you know it’s good for more than that.

Stroke of Insight

Gül’s next planned study is to give stroke patients MDMA combined with physical therapy.

A stroke is when a blood clot in your head causes part of the brain (usually in one hemisphere or the other, though bilateral strokes do occasionally occur) to die. People often lose some of their range of motion in their face or limbs. Or mental functions such as speech or the ability to recognize faces can be affected. While the damaged parts of the brain remain compromised, it’s been seen that with therapeutic interventions, the brain will regain some of the lost function by essentially “relearning” how.

Typically, people recover some movement during the first three months of recovery. After that, they tend to stay at the same level. But Gül hypothesizes MDMA may be able to return someone to that early post-stroke period of improvement, even if their stroke happened years ago, which may allow them to improve their degree of movement. (Other researchers have been working on the relationship between neuroplasticity and stroke recovery for a while. Gül emphasizes that the “critical period” is a different brain process from plasticity, though the two are often confused.)

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

All the Possibilities

“There are all these therapies out there for treating people,” Gül says. If you’re a stroke patient there’s physical rehabilitation. If you have a speech impediment, you get speech therapy. “Part of the reason we think these therapies don’t always work great is because by the time we give them to people their brains are old and not plastic anymore, not malleable anymore, their ‘critical periods’ have closed.”

“Wouldn’t it be amazing if psychedelics as a class open all kinds of critical periods, not just the social ones? Our idea is that we could take psychedelics and pair them with all of these different interventions: psychotherapy—which is already being done—physical therapy for stroke, language learning for people with cochlear implants, anything where we did an intervention and it didn’t work that well, maybe because the brain wasn’t plastic enough anymore. We could pair it with a psychedelic, restore the malleability of the brain and give those other interventions a better shot at working.”

Gül is one of those people who needs to say things to me three or four times because what she is saying challenges me to confront my own understandings of how things work. Gül’s approach is about the body and healing with psychedelics, not just mental health.

Gül calls her project PHATHOM — Psychedelic Healing: Adjunct Therapy Harnessing Opened Malleability.

“I want to get people excited about the idea of the critical period, so that more and more people take up this critical period reopening framework and test this in their own system,” Gül says. “I hope neurologists will see, oh, I have a critical period, let’s see if psychedelics can work to reopen it.”

Set and Setting and Input

There’s one more implication here, Gül teaches: psychedelics are called “mind-expanders.” For better and worse. If you take LSD with loving hippies out on the playa who teach you that the universe is made of hugs, you might end up a happier person. If you eat LSD with Aum Shinrikyo or the Manson Family, you might end up on the wrong side of the History Channel. Gül’s “critical period” explanation gives an idea of why setting is so super important.

The brain is capable of learning new things, the way a child does. So if you want to use psychedelics to heal, it’s not enough to just sit in a room alone and melt your face off. You have to have healthy inputs going in, a new thing you’re learning, the positive vibrations of a person you love, something honest and good and (hopefully) true. And it’s dangerous to trip around negative influences: arrogant trip leaders or greedy corporations or power-hungry shamans. You might take up those attitudes as your own, and get spun.

Expanding the Mind-Expanders

Through her wide-ranging and creative work, Gül is part of reopening a metaphorical critical period in all of our collective brains, so we can unlearn some of what we thought we knew about psychedelics, ourselves, love, and our relationship to the rest of the animal kingdom.

Gül Dölen “is a deep and broad thinker who challenges the limits of how we may conceptualize the mechanisms by which these drugs work.”

Fred Barrett

“She is a deep and broad thinker who challenges the limits of how we may conceptualize the mechanisms by which these drugs work,” says Barrett.

Gül’s lab is not alone in believing psychedelics can do more than treat mental illness, that they can heal the brain at the physical level and heal maladies we think of as physical. Rick Strassman is studying DMT for brain injury. Yale researchers are using psychedelics to treat cluster headaches. Charles Nichols is studying psychedelics as anti-inflammatories. Athletes have long known LSD can reduce pain and possibly enhance performance.

And while our critical periods are reopening, we can take in new information about the world, in order to live better in it.

That is, if we can hear what Gül has to say. If our ingrained sexism doesn’t lead us to believe the big problems in psychedelics have been solved already by men.

We all may need to re-learn, and try to reopen our own critical periods, to rethink how we listen to women in science. Gül shows us what is at stake.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?