In 1905, several women (and one man), detained at a psychiatric institution in Breslau, now Poland, were administered extracts of the Peyote cactus intravenously. At least two of them had, as it seems, full-blown “mystical” experiences. In 1920, a student of medicine, Leni Alberts, did the very first experiments with pure mescaline at the University Clinic in Heidelberg, which was to become the hotspot of Psychedelic Studies (avant la lettre) during the interwar period. Her experimental subjects were trained psychiatrists, who appeared to be extraordinarily cheerful while “under the influence.” What makes these two historic instances of investigating the plant and its main psychoactive substance exceptional is that they documented aspects that were generally either ignored or even suppressed in the scientific exploration of psychedelics’ original conception: 1) the entheogenic dimension of the cactus-induced experiences, and 2) the therapeutic potential of mescaline, useful for the treatment of depression.

I. Involuntary Epiphanies (1905)

What if He came back,

What if He came back as a plant?

Would you let Him in

Would you let Him into your heart?

– Guy Mount, “Peyote Song”

It is widely known that the very first western “psychonauts” who explored the effects of the Peyote were US and British physicians, and the first series of medicinal experiments with “Anhalonium lewinii” (Lophophora williamsii) were conducted at Columbia University by D. W. Prentiss and Francis P. Morgan. The first, albeit involuntary, female psychonauts, however, were research subjects in a small series of mescaline experiments performed by the influential psychiatrist Dr. Johannes Bresler (1866–1942) in Breslau, then part of the German Empire.

In 1898, Arthur Heffter concluded his pharmaceutical analysis of Peyote by isolating four different alkaloids and identifying “Mezkalin” (C11 H17 NO3) as its main psychoactive ingredient: obviously, it was this substance that was solely responsible for the “beautiful color visions” (schöne Farbvisionen), which were regarded as the distinctive feature of the cactus taken as a whole. Because of the uncomfortable physiological side effects (nausea, headache, etc.) he endured, he doubted that mescaline would ever be of therapeutic value. His uncomfortable experience in part explains why it took more than two decades for mescaline research to take off.

The pharmaceutical company E. Merck kept a very close eye on the latest findings; in 1912 that “Mescalin sulfuricum” was offered for the first time as a research chemical. Therefore, when Bresler did his mescaline experiments in 1905, he used extracts of the plant as a whole. Bresler, who would soon turn out to be an ardent admirer of Adolf Hitler, ensured his readers that he informed the test subjects about the unpleasant physiological effects of the serum, “but of course not about the occurrence of visions.”

Early Mescaline Experiment Subjects Were Mostly Women

Little is known about the experimental subjects except their initials, their age, gender, and a short sketch of their diagnoses : Mrs. Sch. (female, 47 yrs., paranoia), B. (female, 29 yrs., epileptic), L. (female, 25 yrs., epileptic), F. (female, 24 yrs., epileptic), R. (male, 43 yrs., psychotic). Two of them, Sch. and B., had (or were allowed?) to take two turns each. Especially Mrs. Sch., and, for her second “session”, Mrs. B., had religious visions. After meeting both of her deceased daughters, Sch. perceived sacred paraphernalia, encountered three white virgins, and finally even the holy mother of god herself, Jesus on the cross and a number of guardian angels who spoke to her (Bresler did not note what the angels said to her). After hearing bells ring, F. also came across the holy virgin, in the guise of the (Black) Madonna of Częstochowa: “I am in the celestial empire,” B. reports, “I saw Holy Mary, it is as if I want to die,” adding: “I thank god for this beautiful viewing, which I’ve had while I am in my right mind; others might think that I am not in my right mind, since I am perceiving such things.”

Oil painting by Magdalena Walulik.

Bresler seems to have dismissed the significance of these visions concluding that “the content of the visions is in accordance with the life of imagination (Vorstellungsleben), which was to be expected.” It was largely thanks to the candid nature of the reports of the fearless women, who had nothing to lose and could speak freely, that Bresler had the idea that “Anhalonium lewinii” might prove useful “for patients suffering from persistent agonizing optical deceptions, with the mescal-visions pushing them into the background at least temporarily.”

“Mescaline launched the psychedelic era but would play little part in its future.”

Mike Jay

II. Leni Alberts’ Farsighted Observations (1921)

In a recent article, neuroscientist Robin Carhart-Harris stated: “We can no longer ignore the potential of psychedelic drugs to treat depression.” In many ways Carhart-Harris is repeating a claim that Leni Alberts made almost 100 years earlier, when she said:

“The occurrence of a euphoric state […] in all experimental subjects makes me think that mescaline may be useful for overcoming melancholic mind states, provided the unpleasant side effects may be reduced. The visions, which only appear in the dark or with eyes closed, would not necessarily be in the way of this therapeutic treatment.”

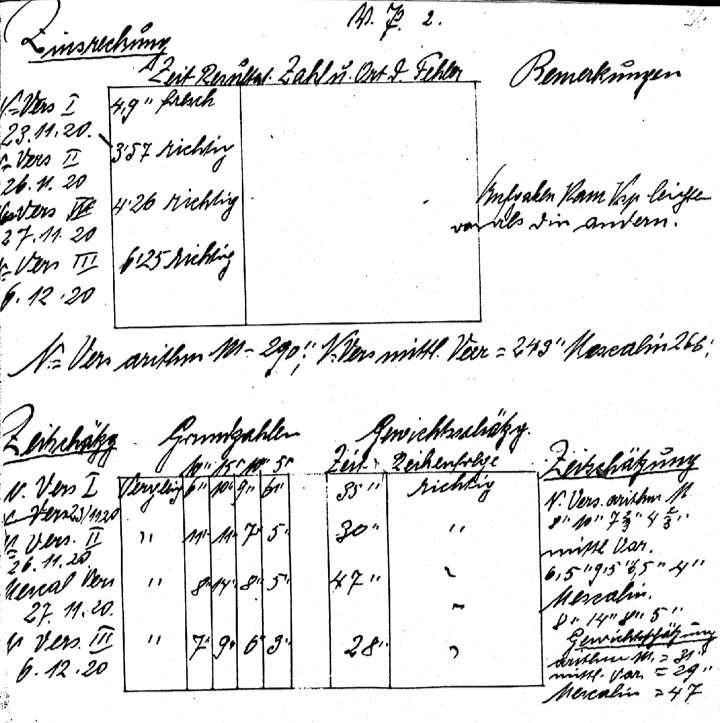

When Alberts identified this feature, she did so almost as an aside. To discover the effects of mescaline she asked her test subjects to fulfill a number of tasks, like simple arithmetical exercises, anagrams, reading tests, and weight estimations. She then compared the outcomes of their tests while “under the influence” to their “sober” results. Alberts observed a general slowing down of cognitive processing capabilities, but mescaline did not seem to have an overall negative effect on their reasoning or problem-solving skills. Despite the small trial, Leni Alberts’ work revealed a hidden promise and inspired further mescaline studies.

Following Viennese chemist Ernst Späth’s fully artificial synthesis, mescaline became a proper scientific “working object.” The mescaline experiments at the University Clinic in Heidelberg precipitated an international research boom. Alberts’ doctoral thesis kicked off this pioneering phase of Psychedelic Studies.

Alberts struggled to get test subjects to concentrate on their respective tasks and noticed their cheerful moods during the mescaline experiments. The contrast with their usual behavior was striking enough for her to describe some kind of euphoric state. Other contemporary researchers, however, did not follow up on this observation.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Why did it take so long for scientists to recognize the salutogenic effects of mescaline?

There is no simple answer. Yet there are likely five interrelated reasons for modern science’s failure to recognize the true nature of Peyote and its derivative mescaline:

- An overestimation of the significance of the imaginary, “visionary” effects as the most decisive pharmacological feature of the drug, classified as “hallucinogen.” Alberts, however, realized that these visionary appearances might obfuscate its therapeutic properties.

- The way that mescaline allegedly mimicked psychosis resulted in a strange epistemological loop, in which the mind-set of the psychiatrists and the institutional setting led them to consider the effects as pathological.

- Mescaline was withheld from patients as well as persons with a history of mental health issues (a taboo even today).

- Science is supposed to be a serious business, and psychiatrists “tripping balls” would have seriously undermined the scientific character of their explorative investigations.

- Finally, science in general is an agnostic endeavor, and it can, for structural reasons, not take recourse to some “deus ex botanica” to explain its results. Hence, it was only after Peyote, Mescaline, LSD-25, etc., became popular drugs, consumed outside the “safe space” of psychiatry and the straight jacket of reductionism, that their therapeutic benefits – arising from their euphorant or spiritual qualities – could be fully taken into account on a broader level.

Perhaps, if Leni Alberts’ observations were followed more closely from the beginning, some of these features would not have taken 100 years to resurface.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?