- Yagé Encounters - October 28, 2021

That night Lucho had six cups. When he went to ask for the seventh, the taita, drunk on firewater rather than the medicine, got upset and didn’t want to give it to him. “Who do you think you are to have seven cups? Not even the elder has seven cups. You are only a child. I’m not teaching you and I’m not going to teach you.” The evil deep in his gaze hurt even more than the rudeness that followed. This is a fake taita, a mediocre one, he thought. What is the use of putting on the necklaces and the crown? Anyone can be crowned. He doesn’t know anything. He hasn’t taught me anything.

He asked him to return the 30 pesos that he had given to be his student. He had earned them by clearing the woods for the explorations of the Texas Petroleum Company in Orito, carrying tools, helping to set up and dismantle the large canvases of the camp, cutting firewood, weeks and weeks in the mountains. Before, the only path that crossed the jungle was the one opened by the missionaries following the indigenous trails, then the military presence grew, and now the oil companies have set up, between Sibundoy and Mocoa, and then Puerto Asís. He only received insults.

It was not yet dawn yet when Lucho left the house where they were taking yagé. Before leaving, the boy flavored the firewater with herbs and red chili seeds that the taita was going to use for healing. He couldn’t hold back his laughter as he imagined him twisting his face after making his soplo on his patients, surprised by its unexpected strength.

He felt anger, disappointment, indignation, and something that he did not know what to call but which rose and fell from his stomach to his chest, pulling him, making him walk fast. I want to learn. I want to know. Who will be my teacher? I want to find him. He climbed the steps carved out of a single log and closed the latch on the door. He didn’t have much. In a corner of the one-room plank house, two pairs of trousers hung from two slightly twisted nails; further on, next to the wood stove, a couple of pots, a cup and two pewter plates, the shotgun, and the machete. On the table that he himself had made sat the battery-operated radio, the lantern with its box of light bulbs, and the 1957 calendar of the “Bodega la Imperial” bar, with its photos of castles and snow-capped mountains, that had come loose from the nail and no longer adorned the wall of unpolished boards, between which rays of light entered, projecting shapes onto the floor. “I want to find my teacher. Who will be the one to teach me?”

Outrage turned to anxiety. He felt so sure of wanting to learn, so eager to follow the path of medicine. His desire to find his master was like that of a thirst that increases with each sip of water. He was not the son of taitas. In fact, his father, ashamed of being Indigenous, insisted that he not hang out with those drunks, but rather learn to grow rice and raise cattle. But nothing could make him change his mind.

Join us for our next conference!

Among his first memories was the night he woke up and felt everything fill with a golden light while the others were snoring. Pictures of celestial gold came out of his heart, tiger men, snakes, and macaws, spiritual macaws, filling the room with pure mystery. Even then, he thought that he wanted to understand, to be knowledgeable like the ancients that his mother told him about. Even then, little more than a baby, without even knowing the meaning of what he wanted. And how he was fascinated by the crowns of the taitas, the sound of the waira and the cascabeles! He felt that jaguar fang necklaces were a more valuable treasure than gold jewelry. He wanted so much to learn.

Lucho fell to his knees, still giddy from the previous night’s intake, his forehead on the rough plank floor, raised five feet from the ground on four pillars. Before closing his eyes, he was distracted by the neighbor’s black pig, who was called “the cuckoo” because of its ugliness, which he could see by looking through the gap between the boards, lying at ease in the shade produced by the floor of his house, its side inflating and deflating with its deep relaxed breathing. He thought of pouring water on it from above, as he used to, just to see it wake up and run off between beleaguered grunts, but the effect of the medicine reactivated his inner vision. He prayed deep in his heart, asking to find his teacher. He begged with the assurance that despair gives.

Next to the river, the soles of his feet bare on the ground, wearing a dirty cushma with frayed edges, a wrinkled old man with a red macaw feather pierced through his nose appeared.

First came Jesus Christ crucified: “I will be your teacher.” He was struck by the humility of the face of God made man, which was lit up with its own golden glow. “And this will be your human teacher.” Next to the river, the soles of his feet bare on the ground, wearing a dirty cushma with frayed edges, a wrinkled old man with a red macaw feather pierced through his nose appeared. He saw the place where he lived in great detail: the settler-style house raised on six pillars from the jungle floor, so high that he could walk underneath; the chagra behind, full of yucca and banana; the stream beyond, and on the other side, a large yagé field, with vines thick as logs, twisting like old colored boas falling from the trees. He saw the little flowers of the yagé open and turn; beyond, the chagropanga vines, and again, the older man, looking at him.

He had to find him. Who was the old man he had been shown? What was that river? It might be the Orito, below. He remembered the curves he had taken before arriving at the taita’s house, just as the vision had taught him. But where was it? Who was he? He remembered the image of an estuary of a river into which a tributary delivered its reddish waters to the main flow. But there are so many estuaries in the Orito! He had to find it.

With what he had left from the settlement after the months with the company, he bought some merchandise and became a traveling salesman, selling clothes, cloth, thread, batteries, knives, and pots in the communities. He always asked about the doctors, those who know about yagé, if there were any elderly people who did. None of the taitas who were presented to him at that time were the one in his vision. He walked so much from one place to another, from village to village that, in a few months, he became well-known and everyone began to order from him.

When he was with the Sionas, they gave him “the pot,” as one afternoon, overcome by hunger and a downpour that caught him in the middle of the trail, he surprised the family of Taita Isaías with his cheek. From afar, they heard the rattling of the pots and metals approaching from the road, growing like a crazy rhythm of drums, until he appeared: all wet, carrying his goods tied with rope on his back, still a child. It was raining so hard that not even the dogs came out to bark at him. From outside the house, he greeted them and asked permission to go up.

“Thanks, Doña Zoila,” he told the taita’s wife, who was weaving a hammock with other women sitting on the plank floor. After a while, he took out a round, well-polished river stone, white with purple stripes almost like a tiger’s, and stood, rubbing it.

“Doña Zoila, could it be that, since the stove is lit, you let me cook a stone soup?”

Perhaps because they did not understand Spanish well, or perhaps, out of simple curiosity, they gave permission, pointing with their finger towards the corner of the house where the wood stove was located, supported by a low wooden plank table, on the which rested the box of earth for the embers. Lucho poured water into one of the pots that he carried to sell, put it on the fire, put the white stone in it, and waited for it to boil.

“Mmm, how good this broth would be with a plantain. Doesn’t Doña Zoila have a plantain left over?” The woman passed him two plantains that the young man peeled, split, and added to the soup. After a while, he put the spoon in and tasted it. “How tasty! And what would it be like with a piece of yucca! Don’t you by chance have a little yucca out there?” He peeled a long yucca that was passed to him and soon saw how the yellow pieces were softening in the water. He repeated once more the ploy with the chili pepper, and would have got some game if the women had had any. In the end, he served himself the soup in a pewter plate, and since no one else wanted any, he finished the pot himself. He shook the still-hot stone, put it away, and went off giving thanks, taking advantage of the fact that the weather had now cleared. Behind him, the Sionas listened to the pots rattle until the drumming disappeared amid the cries of birds and monkeys.

He walked until, at last, he found his teacher. He was undeterred. He had to pay for a motor boat until he was well down the Orito River, where he recognized the red water estuary, the house on stilts with a palm leaf roof, the chagra, and, above all, the old one, who, at first, denied who he was. In person, he looked a little older than in his vision: his nose pointed and curved like an eagle’s, pierced by the long feather of a red macaw; grey eyes, almost white, almost blue, almost water, a river well; his ears were larger and longer than normal, framing the dark, wrinkled face that seemed more round because of the fringe with almost no grey hair, cut in a perfect straight line well above the forehead. He was sitting outside the house smoking, looking out over the river, as if he had been waiting for him.

“Good morning,” the boy approached him confidently. “I’m selling clothes. Take a shirt; it’s on me.”

“Mijo,” shouted the wise old man, “come and choose. Tell Mijo to choose; his choice is my choice.”

After the son selected one of the few garments that he was selling, without hesitation, he asked:

“Can’t you do a little healing for me? It’s just that I’ve been sick.”

“I am just a poor Indian, what are you coming to me for that? You come from the town to the hills where we don’t know things. Here we are just ignorant Indians. The doctors are there, go and get an injection.”

“I am also an Indian, taita …”

He had to come back two more times, always begging him for healing, until the boy found him curing a woman; then, the older man could no longer refuse.

“Taita, please help me because I’m sick,” he said.

“All right, if you insist on coming to the rough Indians… Bring me a bottle of firewater and some cigarettes.”

The boy bought a flagon and several packages of Pielroja cigarettes and returned as soon as he could to see if he could finally be at the older man’s side. That’s how it went. This time, almost immediately after saying hello, he sat down on the rough wooden stool the taita pointed to.

“You’re healthy. The sick one is me.” Taita said, as he took the waira and blew it. “What you have is a bit of nonsense stuck inside your head.”

As he healed him with the waira, singing softly with his eyes closed, it started to rain. The air became so humid that they seemed to breathe steam. The taita’s wife brought them chucula. First the boy took it, and then, from the same totuma gourd, the wise man.

“Taita, couldn’t you give me some yagé?” he asked, without embarrassment.

“Yagé? What’s that? I’ve never heard of it,” replied the old man, seriously.

“Taita,” he continued, with shameless audacity, wanting to provoke him, “I take up to six cups. I was learning with a man and I took six from him.”

“You?! Not even of milk because your belly would get too big!”

“When will you give me a taste of yours?”

“Okay, come in a fortnight from now to see if I can get a little bit.”

There were some 15 drinking that night. They were all apprentices of the taita. The yagé house was a palm leaf shed supported by four poles driven directly into the ground in a clearing in the jungle not far from the elder’s main house. They all sat on the floor. Unlike his former instructor, Taita Querubín Yocuro didn’t wear a crown or necklaces. In one corner, on a wooden stool, was a white candle whose flame flickered in the wind, sometimes almost dying out. In silence, the apprentices felt the vibrations of the prayer with which the taita conjured the yagé, contained in an aluminum pot. Their skin prickled, making them shiver in the most intense moments, each praying and waiting. After singing to it, the taita distributed the medicine in a glass only slightly larger than those used to drink firewater.

“Are you going to give me so little, taita? Give me another drop,” said Lucho, rudely, when it was his turn.

“Shut up, big donkey. Do you think it’s lunch? Take it quietly, because yagé punishes,” replied the teacher.

The medicine was thick, dark like chocolate, and sweet, as he had never before tasted. What a difference from the bitter yellowish drink that he had taken over the past months from Don Esteban’s hand. No one spoke a word. Even the bush insects seemed to await the effects of the yagé.

He went out to urinate. The stars shone with deep intensity and splendor in the fiery clouds of the Milky Way that, like a dome, circled the dark sky above the hut.

Ha, that’s how taita is. He really went fishing. He fell into the water and turned into an otter to catch fish. Without yagé or anything, he becomes what he wants. Tiger, eagle, water rat.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

“What a scare the taita gave us yesterday,” began one of the apprentices who had come out to urinate next to him. “We all thought that he had drowned; that the river had swallowed him. He told us, ‘The meat has finished. Let’s go fishing.’ At the river, he said, ‘Let’s get into the water.’ He took off his cushma and threw himself into the water. Some time passed, and he didn’t come out, he didn’t come out. ‘Taita, taita,’ we all shouted in anguish. ‘The taita has drowned, he hasn’t come out, he hasn’t come out.’ Joaquín ran to the house and brought the woman, who came crying. We started looking for him downstream, along the banks. We knew where the river would leave him. The old man has drowned, we thought and, crying, we looked for him from one side to the other, among the reeds, among the stones. Nothing, nothing. The woman wept and wept. Nobody found him. He’s been taken by the river, the fish will eat him, the boa has swallowed him. That’s how we spent about an hour, when, suddenly, down there near Pedregales, that beach that is pure little round stones, he appeared, carrying a shadfish in each hand; two huge fish that reached the ground. He was almost dragging them, so big were they, pulled by their guts. Ha, that’s how taita is. He really went fishing. He fell into the water and turned into an otter to catch fish. Without yagé or anything, he becomes what he wants. Tiger, eagle, water rat. And, he got two good fish: two very big shadfish. We ate very well and laughed at the fright.”

Dizziness came like an earthquake that forced the boy to lie down. He felt the ground open beneath him, thundering as if it were ripping apart. The space around him vibrated and resounded as if he were inside an immense bell, ringing colors. His entire body shook and ached.

“Ha, the little boy is suffering,” said a dark young man with a coastal accent who was next to him.

“Me? No, nothing,” the boy proudly replied.

“Shall I serve you then the second?” Taita took the opportunity to ask him when he heard it.

“Sure, taita, just serve it ,” replied the daring and insolent boy, pretending to be strong.

He took it, gathering courage without knowing from where, to hide the discomfort that reminded him of malaria fever. He lay back down, no longer able to to hide. Each limb jumped like one of the taita’s shadfish, struggling against suffocation out of the water. He swallowed the medicine again a couple more times and resisted vomiting as long as he could.

“See, this young man is a good learner,” said the taita aloud. “He’s enduring the struggle.”

Each word of the taita resounded in a metallic and guttural echo, between the aquatic and stellar, losing itself in the dark distance of space behind the closed eyes; each word repeated a millisecond later in each dimension of the inner sky until it ceased to be a word and became only force and vibration. Dark and deep immensity of the starless sky, vertigo of the empty infinity, without north or south or east or west, without above or below, only space without form or body, nothing contained, nothing containing. Astral dread.

In the infinity of the empty universe, a blade of grass, a grain of sand, in which all life, past, present, and future was found; all the men and women, animals, and plants that have existed, that are and that will be; and, when they approach the blade, inside, an immense honeycomb, each hexagonal cell containing a species in turn, full of infinite cells; each one of them, a member of the species. A blade of grass in a pasture growing inside a blade of grass; a grain of sand on the beach that extends into a grain of sand floating in the vastness of the universe; that is, each one; that is the only thing that I am.

The jungle in darkness; not only due to lack of light but also of color. Huge trees with leaves of all shapes, fruits of all flavors, but no color. Vines of all kinds hanging down from the branches, mighty rivers, the anaconda, the jaguar, the tapir, the peccary, the hummingbird, the butterfly and the mosquito, large and small monkeys, armadillos and macaws like shadows, mountains and huge stones; smells, yes, but no color. There, crawling, groping for food in the mud, like a mountain pig digging with its nails, almost walking on all fours, the man and the woman, naked, without intelligence or word or tool. Eating roots, chewing stems, moved only by hunger, attracted merely by smell. It is almost the same to have eyes open as closed in the primordial darkness, when there is still no difference between day and night, when there was not yet the Sun. Original night; nothing from the beginning.

From the union, the Sun arose, radiating colors like human flashes; little men playing flutes and drums, the music of creation. Adorned with feather crowns and necklaces, they went down to the jungle, entering everything, bringing more and more colors to the world.

Then, the man found a piece of the sacred yagé vine. He was there waiting for the divine gift; a gift to be discovered, waiting for the appointed hour. He broke it and gave half to the woman. They sniffed it and ate it. Immediately, warm, between her legs, for the first time, her menstruation blood dripped down and, from the piece that was left, the stem of an immense flower rose into the sky and opened in grey splendor. A small hummingbird took flight and grew and grew until it reached and fertilized it with its needle-like beak. From the union, the Sun arose, radiating colors like human flashes; little men playing flutes and drums, the music of creation. Adorned with feather crowns and necklaces, they went down to the jungle, entering everything, bringing more and more colors to the world. Its music, carnival of the origin, enveloped the man and the woman and awakened their understanding, making their intelligence flourish like a fire that ignites and transforms everything. Each thing began to have a name. The words sprouted from the music that gives understanding. It was the origin, the beginning, the sacred gift of the yagé vine.

“Well, who’s going to buy some more?” The taita’s question pulled him out of his vision.

It took him a while to remember where he was and who he was. It was like being pulled from one world to another, from one way of existing to another; suddenly, ceasing to be a stone, a tree or a snake and entering the form of men; from the cold and viscous moisture passing to the warmth of the soft skin, from the electric silence to the clarity of the word and the joy of singing and laughter. They had run out of firewater and cigarettes, it seemed already to be dawn, and the taita wanted someone to bring more.

No one answered, thinking that the older one was asking just to ask. Who could go to the town at that time; more than two hours walking, still dark, raining? “Doesn’t anyone want to smoke? Doesn’t anyone want a glass of firewater? It will be my turn to go,” said the taita before the general silence. He filled the cup with yagé and sang to it for a long time with a force that shook the trees and brought down leaves of colors and shapes they had never seen before. Then, the wise old man took the medicine and went to bed. Lucho did not miss the chance to joke about the older man’s snoring: the canoe engine that almost broke down, lacks oil, so he will get to town quickly to bring cigarettes and firewater, hopefully he didn’t forget to put gasoline on it there for the return trip.

After a while the taita coughed and woke up:

“Now, who wants to smoke? Does anyone want a drink?”

Before the group of astonished apprentices, he brought out a bottle of firewater and a packet of Pielroja cigarettes. “Didn’t I tell you? Lazy. It was my turn to go. There, I met your brother in the bar. He asked me if I wasn’t with you and he bought me a soda. I took it and I came” he told Joaquín. They all received a drink and a cigarette; even Lucho, who, having just turned twelve, smoked that night for the first time.

He was still pumped up at dawn. When they returned to the taita’s house, there was a lady with a child in her arms waiting for him to receive a healing. He brought smoked peccary meat, which they ate with boiled yucca and chucula. Before going down to heal the child, the wise man warned the young man: “This is my little bench, and this belonged to my father, the late Taita Patricio, King of the Amazon. Don’t ever sit on it.”

It was as if they had told him the opposite. “Big fool, didn’t I tell you not to sit down there?” The taita rebuked him when he returned. Lucho couldn’t get up from the bench, pale with shock and surprise. He had no strength, a piece of metal on a powerful magnet. “Let’s see; give me your hand.” The older man grabbed him, blew on the crown of his head, and at once, the boy was able to stand up.

In the eight years that he spent with his master, stubbornness gradually became force of will, a requirement of every apprentice taita. “If I died, I died; or if I learned, I learned,” he used to say to his companions; until, one by one, they left their apprenticeship, and Lucho could only joke with the spirits.

Glossary:

Taita is the common denomination of the traditional Indigenous healer of the Putumayo region in Colombia. It comes from Quechua and means “father.”

Yagé is the name of both the vine (Banisteriopsis Caapi) and the sacred brew made from the vine and the chagropanga leaves (Diplopterys cabrerana). In other Amazonian regions, it is better known as “ayahuasca.”

Chucula is a traditional drink of the Cofán people made of cooked plantain.

A tutuma is a hemispherical bowl made by drying the fruit of the totumo tree and splitting it into two.

Waira (wayra) is the bundle of the waira sacha leaves used by taitas for healing, chanting, and other ritual purposes.

Cascabeles are Amazonian rainforest seeds that are used to make necklaces because of the rattling sound that is created when the seeds hit each other.

In the cleansing ceremony the taita will also perform a soplo, drinking a little of the chonduro plant remedy and then blowing a mist on the body of the sick person.

A cushma is a one-piece tunic used by different Indigenous peoples in the Amazon.

—–

Note:

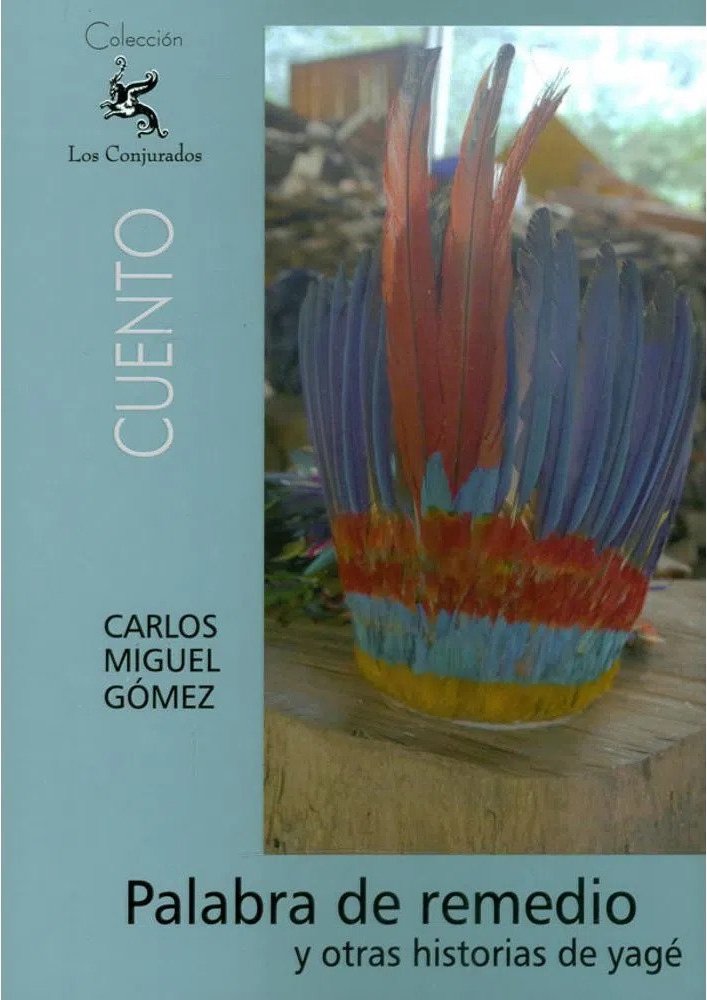

This excerpt appeared in Palabra de remedio y otras historias de yagé (Bogotá: Común presencia, 2020). It was translated from Spanish to English by John Milton.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?