- A Century of Mescaline - April 30, 2021

- The Encounter That Introduced Peyote to Western Science - August 9, 2019

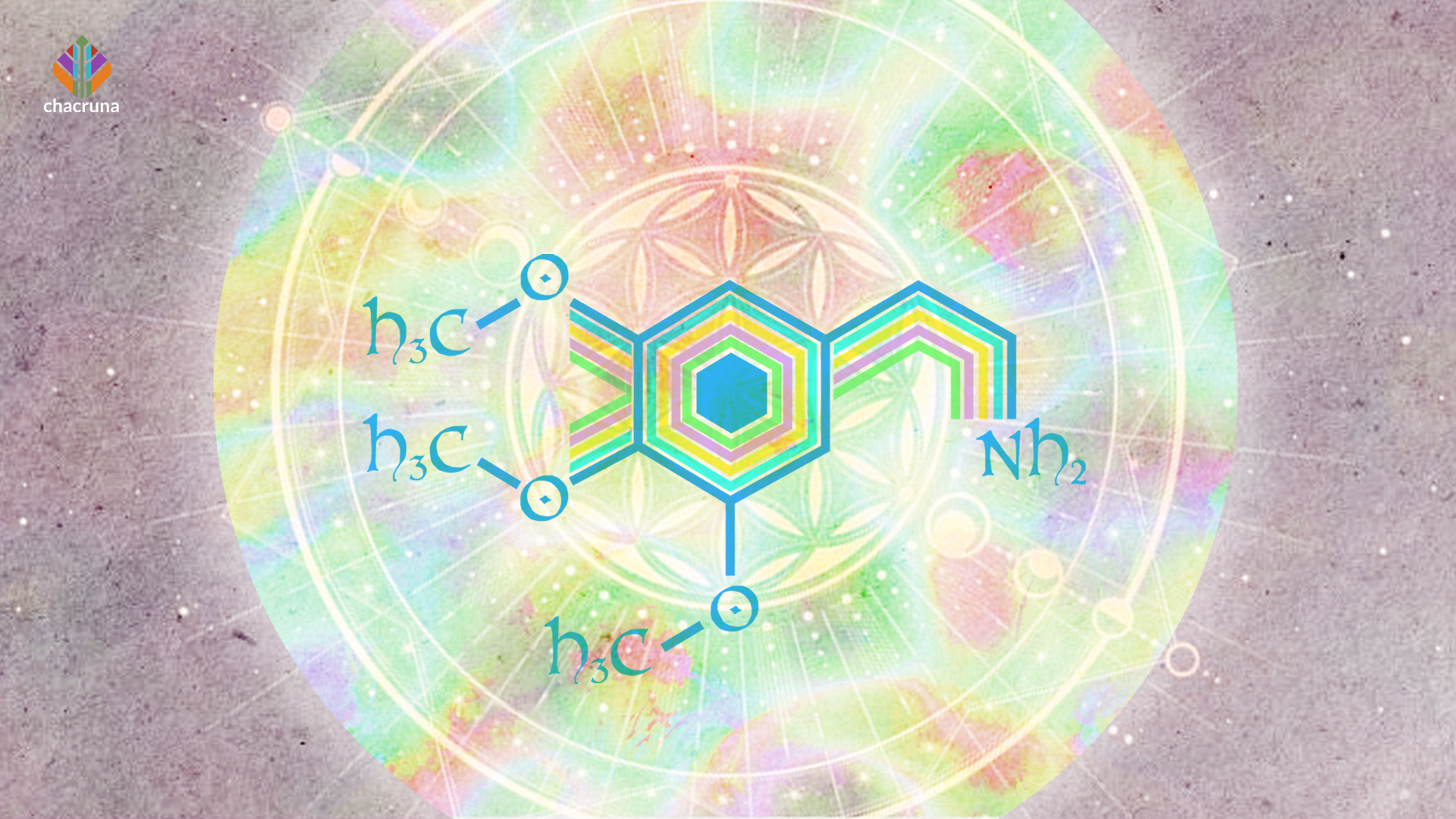

Mescaline was first synthesized in 1919 by the chemist Ernst Späth in the laboratories of Vienna University, from the organic base of 3,4,5-trimethoxy-benzoic acid, an oil found in eucalyptus. It was the first of the compounds that we now call “psychedelic” to be created in the laboratory, and, over the next century, it would make a distinctive contribution to Western science, medicine, art, and literature.

The compound had originally been isolated from the peyote cactus in 1897 by the chemist Arthur Heffter in Leipzig, Germany. Heffter had painstakingly separated out the resins and alkaloid contained in the cactus and determined by self-experiment that the main psychoactive or vision-producing ingredient was an alkaloid he named “mescaline,” after mescal, an alternative name for peyote.

Ernst Späth’s laboratory synthesis of the compound established that mescaline’s formula was 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine, slightly different from that structure that Heffter had proposed. But it also changed its identity, from a plant extract to a “pure white drug,” a product of modern pharmacology. Just as pure cocaine had become a standard pharmacy product, with its botanical origins in the coca leaf reduced to a footnote, mescaline now joined the ranks of modern research chemicals. Späth proceeded to synthesize several more organic compounds with similar molecular structures, including ephedrine in 1920. That same year, the Merck pharmaceutical company in Darmstadt, Germany, brought mescaline sulphate to market in vials of sterile solution suitable for injecting.

Mescaline was mentally disorienting, and often produced intense changes of mood, ranging from euphoria to anxiety, but under the correct dose, it was possible for experimental subjects to describe the complex visual imagery to researchers as they were witnessing it.

From the beginning, mescaline was of particular interest to scientists for its ability to induce “hallucinations” or visual imagery, typically experienced as “entoptic phenomena”: vivid geometric patterns visible with the eyes closed. These were studied by psychiatrists who connected them to the symptoms of psychosis and the newly created diagnosis of schizophrenia, and by neurologists and cognitive psychologists seeking to identify the optical and brain mechanisms that caused them. “Hallucinations” were an elusive mental phenomenon: They were hard to study, as the contexts in which they were typically experienced—psychotic episodes, high fevers, or other drugs such as scopolamine—made subjects disorientated and hard to communicate with. Mescaline was mentally disorienting, and often produced intense changes of mood, ranging from euphoria to anxiety, but under the correct dose, it was possible for experimental subjects to describe the complex visual imagery to researchers as they were witnessing it.

The most extensive mescaline trials of the 1920s were conducted by the neurologist and psychiatrist Kurt Beringer at Heidelberg University’s psychiatric hospital. Over several years, Beringer injected 60 experimental subjects with Merck’s mescaline solution, often several times, in doses ranging from 200 to 600mg. His eventual report, Der Meskalinrausch (1927), included an appendix of over 200 pages of subjective reports, with detailed experiential accounts and occasional drawings of mescaline hallucinations. Beringer attempted to separate the effects of the drug into three categories: abnormal sensory phenomena, changes in conscious attitudes, and abnormal mental states, but found that they blurred together. His attempts to connect the subjects’ various responses with their different personality types were similarly inconclusive: The hallucinations appeared largely autonomous, with no obvious relevance to the individual who was experiencing them.

The psychologist Heinrich Klüver, working at the University of Chicago, studied Beringer’s reports and made further experiments on himself. He noted that many of the abstract and geometrical motifs described by user of mescaline could be reduced to a short list of underlying patterns, such as spirals, lattices, cobwebs, and tunnels that he called “form-constants.” In his 1928 monograph, Mescal, he speculated that these grids of visual interference offered evidence for how the eye and brain worked together to construct vision, and how mescaline interrupted it.

Klüver’s “form-constants” have been influential across many fields: the art historian Ernst Gombrich drew on them in studying the history of decorative motifs, and more recently, the archaeologist David Lewis-Williams has used them to interpret prehistoric cave paintings as the product of altered states of consciousness. Klüver, however, believed that the analysis of form-constants failed to capture the sense of awe and meaning that was an intrinsic part of the mescaline experience. Other researchers also felt that standard laboratory studies of mescaline were limited, and by the 1930s, several were enlisting writers, philosophers, and artists to describe the experience more fully.

In 1936 two psychiatrists at the Maudsley psychiatric hospital in London gave mescaline to a group of British surrealist artists and compared their work with that produced by their psychotic patients.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Iniciative of the Americas

In 1932, Romania’s leading neurologist, Gheorghe Marinescu, enlisted several artists to paint and respond to music under its influence. In 1934, the Berlin doctor Ernst Joël gave mescaline to the philosopher Walter Benjamin, and in 1935, Jean-Paul Sartre was injected with it at Saint-Anne Hospital in Paris by the psychiatrist Daniel Lagache. The Polish avant-garde artist Stanislav Witkiewicz, under the supervision of the Krakow University psychologist Stefan Szuman, painted portraits on Merck’s mescaline, and credited the drug as co-creator of the works. In 1936 two psychiatrists at the Maudsley psychiatric hospital in London gave mescaline to a group of British surrealist artists and compared their work with that produced by their psychotic patients.

A handful of psychiatrists, such as Walter Frederking in Hamburg, began experimenting with its use in talk therapy, and found it produced dreamy states that could be useful in eliciting childhood memories and symbolic associations.

Studies of this kind focused the attention of psychiatrists on the similarities between some of the effects of mescaline—hallucinations, distortions of time and space, disordered thinking—and the symptoms of schizophrenia. During the 1950s, psychiatry took a biomedical turn, and it was widely studied as a “psychotomimetic” that might hold clues to the chemical basis of the condition. It became cheaper and more widely available after 1951, when a new synthesis was published that started with gallic acid, a precursor chemical commonly used in industrial pharmacy. Mescaline’s metabolic and endocrine markers were studied in tissues and laboratory animals, and it was given experimentally to hospital patients with diagnoses of schizophrenia. A handful of psychiatrists, such as Walter Frederking in Hamburg, began experimenting with its use in talk therapy, and found it produced dreamy states that could be useful in eliciting childhood memories and symbolic associations.

Mescaline was brought to wide public attention by Aldous Huxley, who in 1953, was given an oral dose of 400mg by the psychiatrist Humphry Osmond. Osmond had been experimenting with it at the Weyburn psychiatric hospital in Saskatchewan, Canada, and was interested in its relation, not only to schizophrenia, but to mystical and religious experience. Huxley described his experience of “self-transcendence” in his bestselling account, The Doors of Perception (1954). He and Osmond felt that the clinical descriptions “hallucinogen” and “psychotomimetic” connected the experience too closely to mental illness, and in 1956, they coined the word “psychedelic” to capture its mystical and mind-expanding potential.

For 30 years, mescaline had been the only drug of this kind, but in the late 1950s, it was challenged by the arrival of LSD.

For 30 years, mescaline had been the only drug of this kind, but in the late 1950s, it was challenged by the arrival of LSD. Their effects were comparable in many respects, but their potency differed greatly: A gram of mescaline was around three doses, whereas a gram of LSD was many thousands. This made LSD more intriguing to neuroscientists, as it appeared to act on the brain with far greater precision. It also made it much cheaper than mescaline as a research chemical, and by the early 1960s, it had largely replaced it.

In 1962, the Food and Drug Administration tightened its rules on psychedelic research, raising the standards required to license human trials, and the use of both drugs declined. When the psychedelic counterculture emerged a few years later, the same economic factors made LSD the street psychedelic of choice. Underground chemists such as Augustus Stanley Owsley were able to synthesize millions of doses of LSD for the same cost and risk as small batches of mescaline, which was synthesized only rarely for a smaller connoisseur market.

Perhaps the most consequential mescaline trip of the era was that taken in 1960 by the chemist Alexander Shulgin, which inspired him to explore the relatively neglected field of mescaline relatives and analogues.

Perhaps the most consequential mescaline trip of the era was that taken in 1960 by the chemist Alexander Shulgin, which inspired him to explore the relatively neglected field of mescaline relatives and analogues. He synthesized a series of related phenethylamine compounds, including MDMA (ecstasy), which had originally been developed by Merck in 1912, and developed novel compounds such as 2C-B, with visual effects comparable to those produced by mescaline. Shulgin’s 1991 book PIHKAL detailed the chemistry and effects of dozens of new phenethylamines, many of which have found niches as research chemicals and illicit psychedelics.

Sign up to our Newsletter:

Pure mescaline is still supplied in sulphate or hydrochloride form by pharmaceutical companies, including Merck and Sigma-Aldrich, although its use is tightly controlled and, in recent times, has been largely limited to forensic analysis and criminal toxicology. Other psychedelics, such as psilocybin, LSD, ketamine, and MDMA are now being developed for psychotherapeutic applications, but mescaline has thus far been overlooked; in part, because the strict legal controls imposed in the 1970s have made it difficult to license, and also because the duration of its effects —often up to 12 hours—make it less attractive for clinical use than shorter-acting compounds. In 2020, however, the California-based pharmaceutical company Journey Colab announced their intention to seek FDA approval for mescaline as a mental health treatment. A century after it was first synthesized, the first psychedelic is being rediscovered.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?