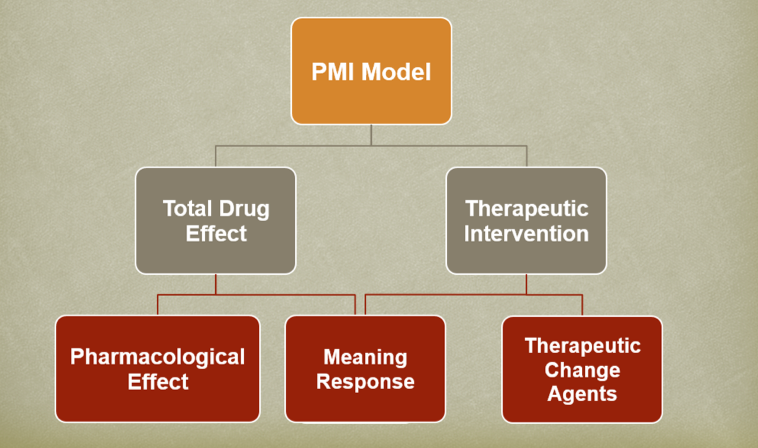

The concept of “set and setting” has been a guiding principle of psychedelic researchers, therapists, and explorers since it was first outlined by Timothy Leary, George Litwin, and Ralph Metzner in 1963. The idea of set and setting was a radical development in identifying non-pharmacological factors that influence how individuals respond to psychedelic substances. It provided researchers and explorers with new means for shaping psychedelic experiences and creating more predictable experience outcomes. While set and setting quickly became popular as a powerful tool for guiding and shaping psychedelic experiences, it remains vague in many ways that limit its utility. I believe a more precise model for maximizing the therapeutic potential of psychedelics is necessary. To meet this need I propose the “Pharmacology, Meaning Response, and Intervention Model,” or PMI Model, which I will introduce below.

The PMI Model is a holistic model that examines drug administration, the context of administration, and paired therapeutic interventions in explaining the therapeutic outcomes of treatment. In this article, I will focus on a single branch of this model, addressing “Total Drug Effect.” If you are interested in a comprehensive exploration of this model, presented within the context of the Native American Church peyote ceremony, you can find it here.

Total Drug Effect

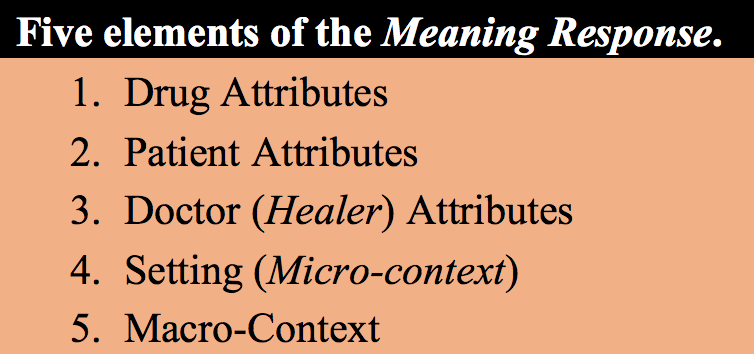

The Total Drug Effect (TDF) is a concept that comes from Gordon Claridge,1 writing just a few years after Leary et al. introduced the idea of set and setting, but is modified here in several respects. Claridge suggests that the full effect of taking a specific drug or medication can only be explained partially by the pharmacology of the substance, and that extra-pharmacological factors must also be considered. Claridge identifies four extra-pharmacological factors that must be accounted for in order to understand the total effects produced by the ingestion of a particular substance; these include: 1) attributes of the drug taken; 2) attributes of the ingester (patient); 3) attributes of the drug provider (doctor/researcher); and 4) the setting within which a particular substance is taken. Cecil Helman2 later suggested the addition of a fifth factor, the “macro-context,” which is included here as part of the PMI Model. All of these factors can be seen as contributing to the overall effects, or TDF, of a particular substance.

Many of these extra-pharmacological factors have been recognized for their effects through studies on placebos. A placebo is an inert substance used as a control in drug studies to help measure the effectiveness of new drugs. Interestingly, despite having no pharmacological activity, research subjects frequently respond positively to these inert substances, a reaction that has come to be known as the “placebo effect.” It has been argued that this term, “placebo effect,” is a misnomer since it implies that a substance is both active and inactive. Daniel Moerman and Wayne Jonas3 suggest that subjects are responding not to the placebo itself (i.e., sugar pills), but to cues during the medication process and in the therapeutic environment that convey particular meanings to a patient about the healing process. For this reason, Moerman and Jonas suggest that these extra-pharmacological effects are better categorized as “meaning responses.” Following the lead of Moerman and Jonas, the five extra-pharmacological factors identified by Claridge and Helman can be understood in terms of the meaning response.

The Meaning Response

So, exactly how do these five extra-pharmacological factors contribute to the Total Drug Effect? Here, we can look to placebo studies to expand upon the significance of these factors and demonstrate their importance. The first factor of the meaning response is drug attributes. The focus of this factor is not on the pharmacological properties of a given substance but rather with the shape, color, taste, smell, and other physical properties of the drug. Placebo studies have shown that subjects report a greater response to placebo pills after taking two rather than one pill.4 Another finding from placebo studies is that subjects respond differently to placebo pills based on their color; subjects receiving red pills report stimulating effects while subjects receiving blue pills report sedative effects.5 These studies suggest that people respond to physical attributes of drugs, such as color or number, and that the way individuals consciously or unconsciously interpret the meanings of these cues influences therapeutic outcomes. Knowing how individuals will respond to the features or attributes of a particular substance provides doctors or other practitioners with a tool for shaping the experience and outcomes of patients.

The next component of the meaning response, the attributes of the patient, is similar to Leary et al.’s concept of set, and focuses on the background and expectations of the individual. Things to consider include a person’s mood, mindset, expectations, and any personal preparations an individual makes to ready themselves for a therapeutic psychedelic session. In many cultures, individuals preparing for the ritual or ceremonial use of a psychedelic plant or plant preparation may follow certain ritual protocols, including abstaining from sex, fasting, or following a ritually prescribed dieta (diet). These are conscious actions an individual can take to help meditate on, and bring focus to, their experience.

Interestingly, the third component of the meaning response, the attributes of the doctor or drug provider, was a factor recognized by Leary et al., but that was ultimately not included in the concept of set-and-setting in any meaningful way. Leary et al6 state, “The expectation of the investigator [drug provider] may have a profound effect on [subjects], both through the kind of preparation he provides and through the kind of setting and interpersonal interaction he arranges for [subjects].” It appears that Leary et al. incorporated the impact of the “investigator,” or doctor, into both the concepts of “set” and “setting,” with the investigator playing the role of shaping the expectations, or “set,” of subjects, as well as taking on the responsibility of creating an appropriate “setting.” This is an understandable position to take, but one that is imprecise and leaves the individual concepts of “set” and “setting” too broad and all encompassing, and which also ignores other important factors, such as the personality and perceived authority of the doctor or investigator.

“Setting” is the fourth component of the meaning response, and here, generally, follows the concept as outlined by Leary et al. When thinking of therapeutic applications of psychedelics, there are a number of things a therapist or other practitioner might consider when deciding on or creating a therapeutic setting. Depending on the patient and the patient’s needs, one might focus on creating a space that feels comfortable and safe; or, patients who harbor some skepticism may need a more formal environment that communicates that the doctor is knowledgeable and experienced in working with these substances. Consideration of the number of people present and their personalities and relationships with one another is also important.

Finally, we have the “macro-context,” which generally “refers to the wider social, cultural and economic milieu in which prescribing, and ingestion, take place” (Helman 2001, p. 5). Here, it is important to consider the cultural perceptions of, and values surrounding, a particular substance in the broader community, as well as cultural understandings of the substances’ potential medical efficacy. It is helpful if the therapist and patient have common understandings of health and illness, and how health is restored, whether these beliefs lie in a Western, humoral, shamanic, or other type of medical system. If the therapist and patient are operating under different models or understandings, it will be important for the therapist and patient to find ways to bridge these gaps before proceeding with therapy.

Another important consideration under the macro-context is to look at the broader social and cultural environment. Broad social beliefs and understandings about particular substances can shape the experiences of individuals. For example, a common experience of illicit marijuana users is one of paranoia, an experience that is at least partially due to a cultural context where marijuana use is viewed as deviant, and where the consequences of its use might lead to arrest and incarceration. Similarly, we might expect that individuals whose sacramental use of ayahuasca has been legally recognized to be less vulnerable to paranoia or other negative reactions than individuals using the substance “illicitly.”

Approaching the therapeutic and spiritual use of psychedelics through the framework of the Total Drug Effect, which addresses both pharmacological and meaning responses, provides a much more precise way for practitioners to guide the experiences of their patients in a manner that is both therapeutic and effective. The Total Drug Effect, however, is just one half of the PMI Model, which also explores the types of interventions that can be paired with psychedelic treatments in order to maximize therapeutic outcomes. For a fuller examination of the PMI model, see here.

- Claridge G. (1970). Drugs and human behaviour. London: Allen Lane ↩

- Helman C. G. (2001). Placebos and nocebos: The cultural construction of belief. In D. Peters (Ed.), Understanding the placebo effect in complementary medicine: Theory, practice and research (3–16). London: Churchill Livingstone ↩

- Moerman D. E. & Jonas W. B. (2002). Deconstructing the placebo effect and finding the meaning response. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136(6): 471–476 ↩

- Blackwell B., Bloomfield S., & Buncher C. R. (1972). Demonstration to medical students of placebo responses and non-drug factors. The Lancet, 299(7763), 1279–1282 ↩

- Blackwell B., Bloomfield S., & Buncher C. R. (1972). Demonstration to medical students of placebo responses and non-drug factors. The Lancet, 299(7763), 1279–1282 ↩

- Leary T., Litwin G. H., & Metzner R. (1963). Reactions to psilocybin in a supportive environment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 137(6), 561–573 ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?

Become a Chacruna Member

To make a direct donation click the button below:

Wednesday, June 9th, 2021 from 12-1:30pm PST

REGISTER FOR THIS EVENT HERE

There is growing enthusiasm in Jewish communities about possible ancient use and modern applications of plant medicine in Jewish spiritual development. Psychedelic Judaism introduce new potential modes of healing...