- Betty Eisner: Heroine with a Hitch? - March 17, 2021

Timothy Leary, Ram Dass. These two were as formative for me as they were for the worlds they were a part of; and yet, I had grown very tired of the saga of psychedelic history beginning with their names. When I was a teenage Deadhead, their use of psychedelics to critique and reimagine society started off my thinking about the ways that our reality was socially constructed. Later on, as a psychology student steeped in social constructionism and interested in the history of psychedelics, I began to spot a place that their theories about the social fabrication of reality did not reach—namely, I noticed how their celebrity repeated the white male heroics of a patriarchal society, crowded out the participation of people at marginalized intersections of identity, and ultimately, showed that psychedelics may not have unstitched the social fabric to the full extent they thought was possible.

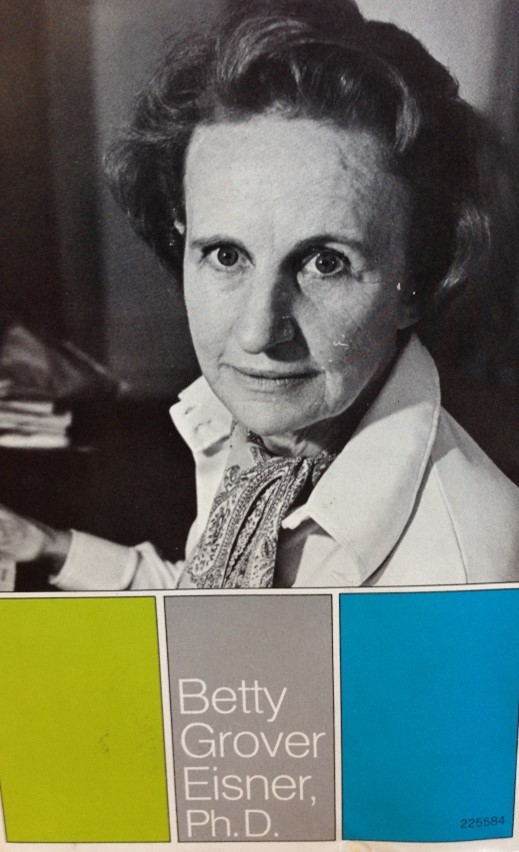

This is how I came to focus my historian-energy on American psychologist and pioneer of LSD-assisted psychotherapy Betty Eisner (1915–2004). The subject of my MA thesis, Eisner was a voracious innovator and networker, laser-focused on developing psychedelic psychotherapy in repertoire as well as in professional legitimacy. She was piercingly curious and intuitive about the inner workings of the psyche, but also deeply disciplined; for all the methodology and metaphysics she invented, Eisner grounded her practice in the psychoanalytic tradition and knew how to present her discoveries to tweeded-out men in mahogany rooms. She helped codify the basics of the clinical psychedelic toolbox, enhancing and theorizing the “set and setting,” such as the use of music, art, and mirrors. She participated in landmark conferences and took an active role in building professional cohesion among an international group of psychiatrists and psychologists who worked with LSD.

When psychedelics were banned, Eisner continued to work on cutting edge psychology, including transpersonal psychotherapy, group therapy, and the formation of intentional communities based on psychotherapeutic principles. It’s hard to read Eisner’s biography and not be struck by the life force she poured into the psychedelic revolution and its spillover into the psychotherapeutic counterculture. Or, to say it another way, Betty Eisner was every bit as deserving of glorification as the 1960s’ all-male cast of psychedelic deities, and I expected that promoting her story could help start to rectify the identity-based exclusions that haunted the history of psychedelics.

“It’s hard to read Eisner’s biography and not be struck by the life force she poured into the psychedelic revolution and its spillover into the psychotherapeutic counterculture.”

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

But there was a hitch. In 1976, a client died in her care, and the circumstances of his death revealed an alternate story about her that was difficult for me to reconcile with the psychedelic champion she had become in my mind. Eisner does not discuss this tragic event in her memoir—her clinical career simply ends June 1978 after a fruitful decade exploring Ritalin, ketamine, and bodywork as legal alternatives to LSD. Buried in the legal files from her hearings with the Board of Medical Quality Assurance of California, I learned that Eisner’s client died after experiencing an extreme physical response to a session that involved Ritalin, bodywork, and “blasting” (a technique for releasing emotions through screaming, related to primal scream therapy) while taking a mineral bath.

According to Eisner’s testimony, the client had been uncooperative throughout the session (perhaps even suicidal), but at a certain point his energy level dropped, and she and her assistant helped him out of the tub and into a bed. As people began to arrive for that evening’s group therapy session, the client’s condition became worse, and Eisner coordinated the group in calling an ambulance and assisting the client. When the medics arrived, they could not resuscitate him. But as they took him away, Eisner and her therapy group were hopeful that he would nonetheless recover to full health.

“As I read through her client testimonies, I learned that everything Betty Eisner described as cutting-edge care was enveloped in boundary transgressions, medical recklessness, and warped client-therapist power dynamics.”

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

An occupational hazard? It didn’t look that way to me. As I read through her client testimonies, I learned that everything Betty Eisner described as cutting-edge care was enveloped in boundary transgressions, medical recklessness, and warped client-therapist power dynamics. In that particular session, clients alleged that Eisner was afraid of calling the paramedics and handling the investigation that would follow, going as far as instructing clients to perform CPR while she thought of a cover story for the police. Before getting to that point, she led the group through chants and energy medicine, which they did despite their insistence on calling for help, because to do otherwise would be to act “out of authority” (paramedics corroborated this, reporting that they walked in to a scene of “15 to 20 people ranging in age from their late teens to late 50’s, standing around the victim holding hands [in what appeared] to be some type of occult ritual”).

Examining these testimonies, it became clear that Eisner had cultivated a group dynamic that centred her as an absolute authority, and according to one client, rendered disobedience to her as “heresy.” This dynamic was years in the making. Her group clients lived together in homes she managed, and she used relocation and eviction as leverage over them. She barred them from seeing medical doctors, instead insisting that their health problems were psychogenic and would best be treated by her. This was especially dire when clients experienced therapy-related injuries such as broken ribs as a result of heavy-handed bodywork under ketamine anesthesia, or unconsciousness as a result of an asphyxiation-based “treatment” Eisner called “containment.” She also established power hierarchies among clients themselves, in one case ordering members of one of her client group homes to restrain one of its residents to a bed for days, restricting the resident’s meals and bathroom visits. Clients complied because their dissent would undo years of therapy—or at least that’s what Eisner told them.

“Paying attention to her surrounding context taught me an important lesson about the nuance of feminist history. Beyond recovering the stories of marginalized individuals, a feminist approach to history can help undo the mode of historical storytelling that centres the ingenuity of individuals in the first place, instead shifting emphasis onto their social embeddedness.”

This dark episode in Eisner’s career reframed my impressions of her as a feminist activist, or a pioneering figure in psychology. It drew my attention toward the social systems into which Eisner was embedded. More than her personal achievements, I became curious about how Eisner’s professional communities in psychology and psychotherapy would respond to her situation, and how these responses reflected expectations about gender and the politics of psychotherapy of the time. Paying attention to her surrounding context taught me an important lesson about the nuance of feminist history. Beyond recovering the stories of marginalized individuals, a feminist approach to history can help undo the mode of historical storytelling that centres the ingenuity of individuals in the first place, instead shifting emphasis onto their social embeddedness.

My supervisor, Alexandra Rutherford recently sent me a short piece by science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin called “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” In it, Le Guin makes the point that a hero’s story rarely makes room for all the details of life in which the hero is embedded, but in reality, the hero’s background is full of understated activity that makes their story possible. Le Guin also continually refers to the hero with the pronoun “he,” because in our history as in our present, social conditions make it most likely that it will be a cis man who makes big gestures from visible places. What if instead, the context itself was “the hero”? To Le Guin, this would look like less cycling between triumph and tragedy, and more attending to the richness and subtlety of the worlds that carried the lives of folks like Betty Eisner.

Support the Eagle and the Condor’s Ayahuasca Religious Freedom Initiative

This last thought is especially important for reclaiming Eisner’s place in the history of psychedelics. She made lasting contributions and deserves credit as an innovator, networker, and agent of cultural change. But more interestingly, the shape of her successes, adversities, and mishaps reflect a world that was poised to respond to her with particular assumptions about gender and who has the right to challenge authority. Eisner’s story is complex, and to make sense of her life, we need to pay attention to the social context in which she was embedded: What does her navigation of professional spaces reveal about how the disciplines of psychology and psychiatry were gendered, and how were psychedelics therefore gendered? What do her interactions with professional authorities reveal about conventional attitudes toward psychedelics, and how were these attitudes laden with power? And what does her inventive thinking as a therapist reveal about changes to notions of selfhood and wellbeing in the countercultural era, and what did women have to contend with while working at the crux of such profound change?

Contextualizing Eisner within these structural power dynamics encourages us to think beyond her personal triumphs and tragedies, to challenge the common notion that psychedelics were championed into existence by scientific renegades, and to instead explore how psychedelics were constructed in dialogue with an array of social norms. This is particularly crucial for the history of psychedelics, as these substances are often suggested to help us look behind the veil of society and to expose the tyranny of hegemony. While there is truth to that, a contextual look at Eisner’s life shows that psychedelics are also socially constituted, shaped by people and institutions to satisfy their own complex intentions. So yes, Betty Eisner deserves to be remembered alongside other psychedelic pioneers for her ingenious shaping of clinical practice to meet the therapeutic potential of psychedelics—but also to show the ways that psychedelics themselves were shaped by the people and societies with which they coexisted.

Art by Marialba Quesada.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?