- Yaminawa Women and Ayahuasca: Shamanism, Gender, and History in the Peruvian Amazon - February 2, 2022

- Ayahuasca Makes you See, and Tobacco Makes You Dream - September 14, 2020

“Last night, I saw my grandfather in a dream and he healed my hand.” Pitsipini’s hand had been swollen for days. Up to that point, he had attributed the swelling to a bruise, but during the oneiric conversation, his grandfather revealed that he himself was the cause because he was angry with his grandson. Being the cause, and therefore the “owner” of this mild case of sorcery, his grandfather was the one to cure it, which he did during the dream state.

The Yaminawa (Panoan) people of the Peruvian Amazon affirm that dreaming is a state similar to that produced by the consumption of ayahuasca: When we dream, the “eye soul” (wëro yuxin) leaves the body. It is a dimension of reality in which special and temporal distances are suspended. In this dream space, the possibilities for conscious interaction with other beings multiply, resulting in an increased probability of both spiritual danger and obtaining knowledge.

When they dream, the Yaminawa can interact with the dead, with people who live far away, with the wëro mëxë dawa spirits that inhabit the sky, or with beings that are visible in normal waking states in animal or plant form. In this way, they get news from their relatives who are far away, become aware of things that are going on nearby but which they aren’t able to see while awake, or divine things that will happen in the future. Dreams show, for example, whether a loved one is going to visit or get sick, if a husband or wife is having an affair, who stole the missing money, or if a peccary herd is nearby. Daily, waking life thus becomes enmeshed with this nocturnal oneiric activity that is essential for people’s social, productive, and emotional existence.

“In dreams, the anaconda taught everything to the man who swallowed and then vomited.”

Dream activity is especially important during the shamanic initiation processes, since the ihu, or owners, of shamanic substances ingested by initiates can transmit songs and other knowledge to them. “In dreams, the anaconda taught everything to the man who swallowed and then vomited.” This sentence summarizes the Yaminawa myth that explains how people learned to use shamanic substances and plants for healing or causing illness. During the shamanic learning process, initiates embody that mythical man. After ingesting a substance extracted from the anaconda’s body, they receive power and knowledge. This is what Xawaxta narrates from his own experience:

We consume the anaconda’s feces… So, it teaches you in your dreams, this anaconda. You can dream about the anaconda. In your dreams the anaconda is praying (kuxuai). … I dreamed of shamans. I dreamed of people doing kuxuai. I dreamed of medicinal plants. You dream everything: You dream that you are collecting medicinal plants, you dream that you are praying to people; then, you wake up and pray.

In addition to this central role in initiation, dreams, as well as ayahuasca visions, are a fundamental means to establish a diagnosis when someone falls ill.

In addition to this central role in initiation, dreams, as well as ayahuasca visions, are a fundamental means to establish a diagnosis when someone falls ill. For example, eating something offered by someone else, being attacked or being locked up in a small space are examples of typical dreams that indicate shamanic aggression. The dreamer’s soul can be subject to actions that lead to illness or death. In this sense, understanding one’s own and others’ dreams is part of shamanic knowledge; but, only people with highly developed abilities, such as Pitsipini’s grandfather, also have the capacity to act in this dream space, to “exercise their power to affect the world” (Kracke, 1992).

While ayahuasca produces visions, the substance that enhances dreaming among the Yaminawa is tobacco.

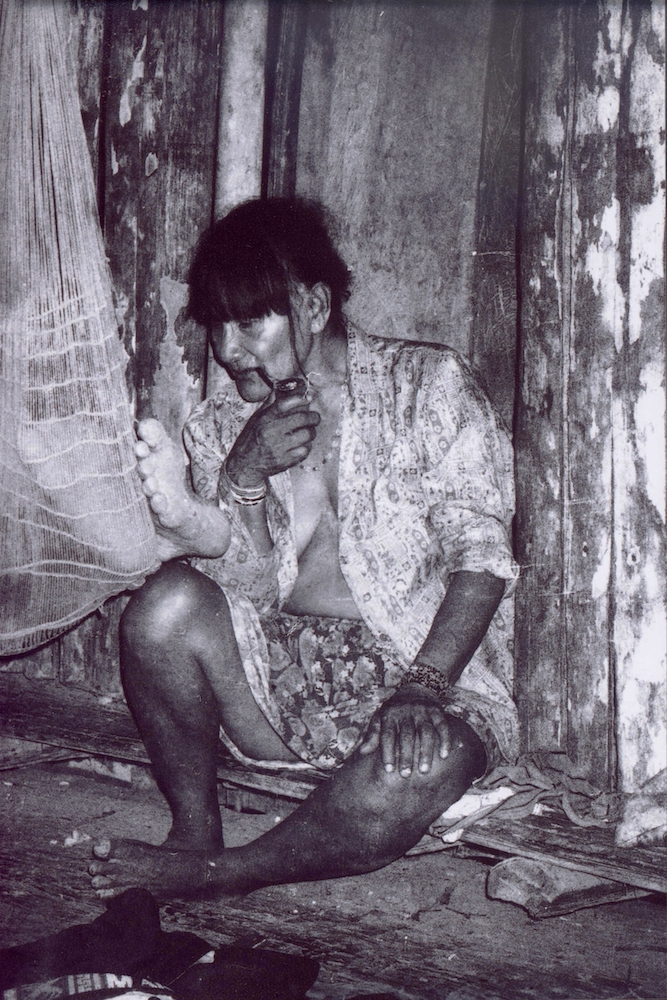

While ayahuasca produces visions, the substance that enhances dreaming among the Yaminawa is tobacco. It is not uncommon to see people, especially the elderly, smoking their pipes, xinimote, in the late afternoon in order to promote dreaming before going to sleep.

Smoking is the most common way of consuming tobacco; however, it is by no means the only one. The Yaminawa have several ways of preparing it. The great ñuwë (shamans with a high degree of power) of the past are always remembered with a wad of tobacco bulging in the cheek. Known as rubëtõ, the wad is made by mixing the tobacco leaves with ash of the jarina palm. In addition to chewing tobacco, it was also prepared as a liquid (rubë txatxi), mixing leaves with water and squeezing them. Ingestion causes strong intoxication and vomiting. Liquid tobacco can also be cooked and mixed with the ashes of certain palm trees until it gets thick. This mixture, known as rubë sawa, is consumed in small quantities due to its potency.

Older men and women, for example, are often called on to blow tobacco smoke on children who sleep restlessly, who cry excessively at night, or when they have diarrhea.

Consumed alone or in combination with other substances (especially ayahuasca, chili pepper, Brugmansia, or Brunfelsia grandiflora), tobacco is one of the main enhancers and vehicles of shamanic power among the Yaminawa, and also the most frequently used. Blowing tobacco smoke is a common treatment for ailments of different types and severity, as well as to ward off evil spirits. Older men and women, for example, are often called on to blow tobacco smoke on children who sleep restlessly, who cry excessively at night, or when they have diarrhea. Likewise, discomfort and occasional pain is also relieved with tobacco. The smoke is said to suck out of the body that which causes pain. However, it is not a substance used only for minor disorders. In the absence of ayahuasca, for example, chewing tobacco or tobacco paste (rubë sawa) may be used during the performance of koxuiti shamanic chants in healing rituals. Moreover, tobacco use seems to have a greater historical depth than ayahuasca itself.

These observations among the Yaminawa reinforce the conclusions of other studies in western Amazonia suggesting a more ancient status of tobacco usage in shamanism than ayahuasca, which appears to have emerged in its current form in this region in more recent times as a result of colonial and interethnic contacts

Based on reports about the practice of shamanism in the past and comments made in informal conversations with my Yaminawa hosts, it appears that ayahuasca was not consumed in the past: “In the past,” Xawaxta once told me,“[the ancestors] did not know how to take ayahuasca, they lived only with rubë sawa.” These observations among the Yaminawa reinforce the conclusions of other studies in western Amazonia suggesting a more ancient status of tobacco usage in shamanism than ayahuasca, which appears to have emerged in its current form in this region in more recent times as a result of colonial and interethnic contacts (Gow, 1994; Lenaerts, 2004; Brabec de Mori, 2015; Shepard, 2015).

In the case of the Yaminawa, tobacco and ayahuasca seem to form the basis for two distinctive styles of shamanism that overlap and, in some sense, complement each other, but that have also affected and adapted to one another. For example, in oral histories and myths, there seems to be a relationship, on the one hand, between tobacco, the figure of the jaguar, and suction as a privileged healing technique associated with a specific type of shamanic specialist, no longer in existence, the tsibuya (“owner of tsibu”) who derives power from tsibu. This is a polysemic term that refers both to bitterness—a quality shared by different shamanic substances that need to be accumulated to become a shaman—and to hard objects the size of a corn grain, introduced into the body during an initiatory encounter with a jaguar. On the other hand, ayahuasca is associated with the figure of the anaconda and chanting as the privileged technique of both healing and shamanic attack, associated with a specialist known as koxuitia (“owner of the koxuiti chants”), whose power comes from the words being chanted. The latter appears to be a more recent and horizontal form of shamanism (Pérez Gil, 2006). And yet, despite these historical and conceptual transformations, and the dominant role of ayahuasca in current shamanism, tobacco and dreaming maintain a central place in Yaminawa practice as privileged modes in interactions with human and non-human subjects.

Art by Mariom Luna.

References

Brabec de Mori, B. (2015). Singing white smoke: Tobacco songs from the Ucayali Valley. In A. Russel & E. Rahman (Eds.), The master plant: Tobacco in Lowland South America (pp. 89–106). London: Bloomsbury.

Gow, P. (1994). River people: Shamanism and history in western Amazonia. In N. Thomas & C. Humphrey (Eds.), Shamanism, history & the state (pp. 90–113). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Kracke, W. H. (1992). He who dreams: The nocturnal source of transforming power in Kagwahiv shamanism. In E. J. Langdon & G. Baer (Eds.), Portals of power. Shamanism in South America (pp. 127–148). Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Lenaerts, M. (2004). Anthropologie des indiens Ashaninka d’Amazonie. Nos sœurs Manioc et l’étranger Jaguar [Anthropology of the Ashaninka Indians of Amazonia : Our cassava sisters and the jaguar stranger]. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Pérez Gil, L. (2006). Metamorfoses yaminawa: Xamanismo e socialidade na Amazonia peruana [Yaminawa metamorphoses: Shamanism and sociality in the Peruvian Amazon] (Doctoral dissertation). UFSC, Florianópolis. Shepard, G. (2005). “Will the real shaman please stand up?: The recent adoption of ayahuasca among indigenous groups of the Peruvian Amazon.” In B. C. Labate & C. Cavnar (Eds.), Ayahuasca shamanism in the Amazon and beyond1(pp. 6–39). New York City, NY: Oxford University Press.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?