To the memory of Grandfather Nemekene from the Muisca People of Suacha (Colombia), who guided us in the preparation of tobacco for the United Nations Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2018.

Westerners who travel to the Amazon or elsewhere in South America in search of ayahuasca have, for sure, encountered other kinds of plants that are part of the ayahuasca ensemble in rural or urban areas.

I am a Colombian national, based in Geneva, where I work with a project to give visibility to sacred plants, including tobacco, at the United Nations and other international organizations. Given the illegality or the legal vacuum of ayahuasca in Europe, Western consumers of sacred plants are realizing the sacred nature of tobacco, which can be used legally in the old continent. Westerners who travel to the Amazon or elsewhere in South America in search of ayahuasca have, for sure, encountered other kinds of plants that are part of the ayahuasca ensemble in rural or urban areas. Indeed, one criterion in judging the level of knowledge and experience of somebody offering ayahuasca in South America, is the pharmacopeia that goes together with ayahuasca, e.g., the perfumes used to help drinkers to undergo through the psychedelic experience.

Tobacco and American Shamanism

Among the plants that go together with ayahuasca, tobacco is one of the most important, considered to be as sacred as ayahuasca. You can do a quick search on tobacco shamanism in the Americas that will persuade you about the sacredness of tobacco in some cultural contexts. In the north of the continent, tobacco was, and remains, central in the “talking circles” held by the Iroquoian Confederation (Von Gernet, 1992). In South America, tobacco is used in at least six different ways by Indigenous peoples: chewing or sucking, drinking, licking, snuffing, smoking, and by enema (Wilbert, 1987). The case of the Matsigenka people in Peru is widely known, where the local name of shamans is related to tobacco: seripigari means“the one who returns tobacco,” according to American ethnobotanist Glenn Shepard (1998), or the “the one intoxicated by tobacco,” according to Swiss anthropologist Gerhard Baer (Rosengren, 2002). For the Huitoto people of Colombia, boiled tobacco leaves are a medicine for skin infections; tobacco is a very central part of Huitoto oral accounts and cultural practices under the name of ambil (tobacco paste). Together with manioc and coca leaf, tobacco constitutes the trilogy of Huitoto sacred plants (Tagliani, 1992). In the oral history of this people, a cultural hero is able to fly using coca and tobacco leaves as feathers (Rangel, 2004), a clear reference to the shamanic flight induced by sacred plants.

The sacred use of tobacco is being rediscovered by both Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous individuals. This has been possible thanks to the global expansion of ayahuasca and local processes of ethnic identity recovery. Social groups who did not previously see themselves as Indigenous, now claim an Indigenous identity based on the production and consumption of sacred plants. Indigenous Muisca (*) people in central Colombia have exploited their links with Huitoto People from the Amazon to adopt ambil and tobacco snuff, also known as rapé among urban ayahuasca drinkers. The Muisca people utilize the name hosca instead of rapéin an attempt to recover the Chibcha language’s pre-Colombian word for tobacco. Tobacco is part of the purga (body cleaning) that precedes ayahuasca consumption in northern Peru. In Colombia, the purge with tobacco is part of the learning process for people who are being prepared to blow tobacco powder during ayahuasca ceremonies.

Tobacco to Heal Catherine de’ Medici’s (1519–1589) Headaches

The legend says Catherine de’ Medici was treated and possibly healed of her headaches thanks to the tobacco powder prepared by French physician Jean Nicot.

The use of tobacco as a medicine has been attested to in Europe for a long time. The legend says Catherine de’ Medici was treated and possibly healed of her headaches thanks to the tobacco powder prepared by French physician Jean Nicot. In his memory, Nicot’s surname was adopted by Linnaeus to baptize the tobacco genus one century later: Nicotiana (Rogers, 2020). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the snuffing of tobacco powder, or rapé,was a very common habit in Europe, as we can see in the literature and art of that time. Nowadays, the French-origin word “rapé” is currently adopted to refer to tobacco powder in urban ayahuasca ceremonies held in Spanish and Portuguese speaking countries and in the USA. Since the introduction of rapéin the French court during the second part of the sixteenth century, tobacco has been progressively used as a stimulating recreational drug in Europe.

Along with ayahuasca globalization, the reintroduction in the twenty-first century of tobacco in Europe has opened an opportunity to recover the sacredness of this plant in contemporary societies.

The related health problems “of smoking and other forms of tobacco use,” recognized in the second half of the twentieth century, has led to classifying tobacco consumption as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) (1986). Along with ayahuasca globalization, the reintroduction in the twenty-first century of tobacco in Europe has opened an opportunity to recover the sacredness of this plant in contemporary societies. We invite you to quickly review the work with tobacco made by two organizations based in Europe that keep strong relations with South America.

Tobacco and NGOs in France and Switzerland

La Maison qui Chante (“the singing house”) is an association established in Lyon according to French civil law. It is the European representative of Takiwasi (“the singing house” in Quechua), a center based in Tarapoto, Peru. In Peru, Takiwasi has the freedom to use ayahuasca in its ceremonies. Takiwasi has been advocating for the use of ayahuasca in France through its French representative association in Lyon for a long time. Until 1999, La Maison qui Chante and the Santo Daime Church in France could legally import the ayahuasca drink for their internal consumption; they lost this right when the French health minister labeled the vegetal species Banisteriopsis caapi, Banisteriopsis rubyana, Psychotria viridis, Diplopterys cabrerana, (ayahuasca ingredients) and Mimosa hostilis (Jurema), as “narcotic plants” (Bauchet, 2005).

According to Bourgogne, a psychoanalyst in charge of tobacco ceremonies in France, she treats depression, drug addiction, and neurosis guided by the spirit of tobacco.

Given the legal impossibility of using ayahuasca, La Maison qui Chantehad redefined its activities, focusing on tobacco as a sacred plant. The Association now organizes one-week tobacco retreats in the French mountains. In doing so, it uses the long experience of Takiwasi in cleansing ceremonies and treatment of drug dependency. According to Bourgogne, a psychoanalyst in charge of tobacco ceremonies in France, she treats depression, drug addiction, and neurosis guided by the spirit of tobacco. She had her first encounter with the tobacco spirit “during an ayahuasca ceremony; the spirit was sad. He told me, ‘I am a powerful medicine but nobody pays me any attention.’” She uses tobacco with people who “have experience with Amazon medicine but do not have the possibility to drink ayahuasca in France because of legal matters. Even if we do not agree with the state banning ayahuasca, we do not want to conduct illegal practices that would put in danger the drinkers and the medicine” (Bourgogne, 2009).

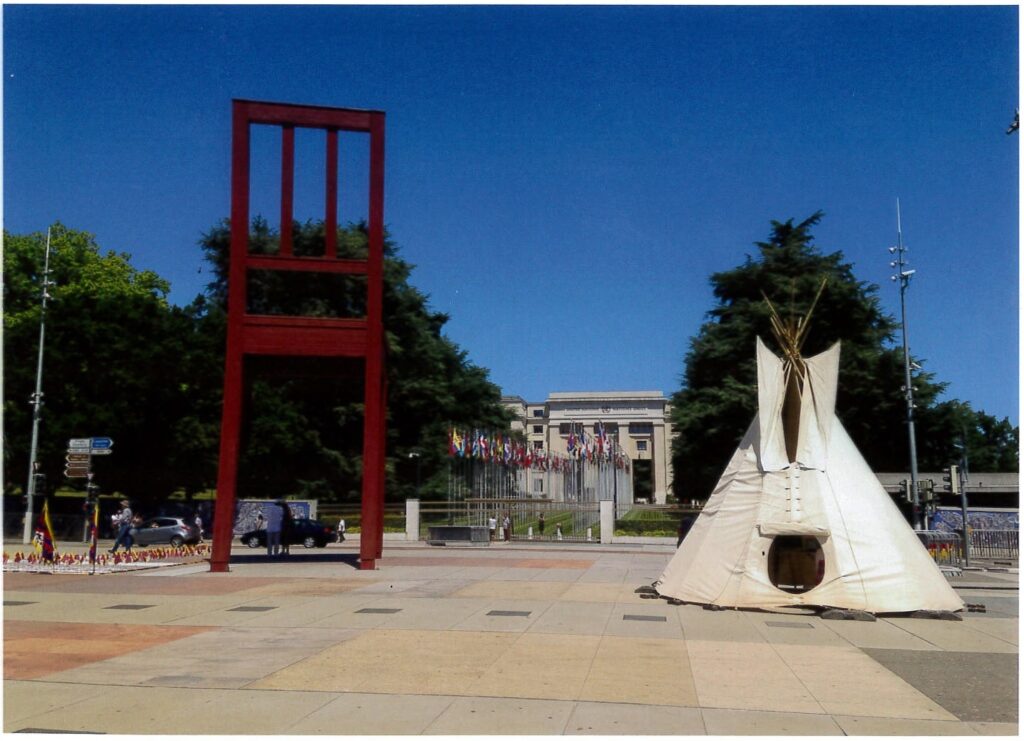

Since 2018, Maloca International has also held a tipi in front of U.N. headquarters where tobacco ceremonies take place during international conferences in partnership with the association Mos-Espa and with the agreement of Swiss authorities.

In Switzerland, the association Maloca International uses tobacco with a different focus at the United Nations Headquarters and nearby in Geneva. Since 2014, tobacco has been consumed during international conferences by Maloca International delegates and fellow NGO attendants, to concentrate, to listen, and to speak. At the same the time, the use of ambil and hosca is a way to affirm non-commercial tobacco consumption in the Western world. In Geneva, Maloca International provides tobacco for musical performances and organizes talking circles with a variable number of people and different objectives. Since 2018, Maloca International has also held a tipi in front of U.N. headquarters where tobacco ceremonies take place during international conferences in partnership with the association Mos-Espa and with the agreement of Swiss authorities. These ceremonies have been named Kubun Istysuka, the Muisca denomination of “talking circle,” because part of the tobacco available for the ceremonies is grown by the Muisca community of Soacha, Colombia. In 2020, this tipi is scheduled to be at the Place de Nations the first week of December (see photo below). In Switzerland, there are also some individuals who hold tobacco cleaning ceremonies.

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (2003) and Tobacco Shamanism

Together with ayahuasca, the sacred use of tobacco has traveled to Europe and, today, tobacco ceremonies are well-established in Europe. Maybe this is the opportunity for some Europeans to rediscover the medical properties of tobacco, explored earlier by Jean Nicot. This could eventually create a narrative on tobacco to complement the narrative held by the World Health Organization with its 2003 Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the first international instrument ever negotiated at WHO headquarters in Geneva.

Back in America, some Indigenous communities are reflecting on ways to apply the WHO FCTC, while making a clear difference between this and their sacred practices based on the tobacco plant. One key issue here seems to be the promotion of growing Nicotiana rustica as an alternative to the commercial Nicotiana tabacum species, although this way of seeing the problem is a very simplistic chemical approach; it ignores the intangible mental and emotional process of growing sacred tobacco (Maron, 2007). I hope that this publication raises awareness about the need for more research and publication on best practices with tobacco.

Art by Mariom Luna.

References

Bauchet, C., Bourgogne, G., Bourgogne C., Mabit, J., Vaillant, M. C., Vacandre, M., J-P., Association pour la liberté du Santo Daime, & Association La Maison qui chante. (2005, April 20). Recours pour Excès de Pouvoir. Mémoire Introductif et Ampliatif à Messieurs les Président et Conseillers composant le Conseil d’Etat, contre un arrêté du 20 avril 2005 modifiant l’arrêté du 22 février 1990 fixant la liste des plantes et substances classées comme stupéfiants pris par le Ministre de la Solidarité, de la Santé et de la Famille. Paris. [Remedies for excess power. Introductory and amplifying memorandum to the presidents and councilors composing the Council of State, against a decree of April 20, 2005 amending the decree of February 22, 1990 fixing the list of plants and substances classified as narcotics taken by the minister of solidarity, health, and family.] Paris.

Bourgogne, G. (2009, June) Usage des purges de tabac dans le processus thérapéutique [Use of tobacco purges in the therapeutic process]. Presentation at the International Congress of Traditional Medicines, Interculturality and Mental Health, Tarapoto, Peru.

Maron, Dina Fine (2018, March 29). The fight to keep tobacco sacred. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-fight-to-keep-tobacco-sacred/.

Obando Rodríguez, J. (2018): Música Muisca y sus Nuevas Sonoridades [Muisca music and its new sounds] [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Vienna.

Rangel Urbina, F. (2004). Dïïjoma el hombre serpiente águila: mito uitoto de la Amazonía [Dïïjoma the snake eagle man: Uitoto myth of the Amazon]. Bogotá: Convenio Andrés Bello.

Rogers, K. (2020). Jean Nicot de Villemain. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jean-Nicot.

Rosengren, D. (2002). Cultivating spirits: On Matsigenka notions of shamanism and medicine (and the resilience of an Indigenous system of knowledge). Anales Nueva Epoca 5, 85–108.

Shepard Jr., G. (1998). Psychoactive plants and ethnopsychiatric medicines of the Matsigenka. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 30(4), 321–332.

Tagliani, Lino (1992). Mitología y Cultura Huitoto [Huitoto mythology and culture]. Quito: Abya-Yala, CICAME.

Von Gernet, Alexander (1992). Hallucinogens and the origins of the Iroquoian pipe/tobacco/smoking complex. In C. F. Hayes, III (Ed), Proceedings of the 1989 Smoking Pipe Conference, (Research Records 22, pp. 171–185). Rochester, NY: Rochester Museum and Science Centre.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1986, May). WHA39.14 tobacco or health. Fourteenth plenary meeting, Geneva.

Wilbert, J. (1987). tobacco and shamanism in South America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

—

(*) Editorial note:

The Muisca community settled in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in Colombia is far from being that pre-Hispanic culture already extinct and synonymous with a pre-colonial past. Although the capital and most populated city of the Republic of Colombia, Bogotá, was raised in a considerable part of its territory, the Muisca never disappeared. At present they are organized around the figure of indigenous councils, most of them recognized by the Colombian state, which since the Constitution of 1991 ceased to be a monocultural state to recognize itself as a multiethnic and multicultural one. The Muiscas define themselves as a nation in reconstruction and lead processes of territorial and cultural recovery supported by the knowledge of the elders of their community (abuelos) and the orientation of other indigenous peoples such as the Kogi of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (Obando Rodríguez, 2018.)

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?