- Cultural Appropriation and Misuse of Ancestral Yagé Medicine - February 5, 2018

- Cultural Appropriation and Misuse of Ancestral Yagé Medicine - February 5, 2018

- The Guardians of Amazonian Forests in Defense of Life - June 24, 2020

- Cultural Appropriation and Misuse of Ancestral Yagé Medicine - February 5, 2018

Spirituality and Yagé

Territory, culture, self-government, and spirituality: that’s what’s most important for us.

The curacas, our men of wisdom or traditional doctors—harmonize relations within the community and heal illnesses. The curacas know the territory, know and communicate with the spirits of Mother Nature, and feel the sacred energy sites of the territory. The curacas have studied and practiced the medicine for ten, twenty, thirty and even forty and fifty years. Often, they come from lineages of medicine men and medicine women. The curacas are our spiritual neurologists. Learning the medicine is an arduous lifetime mission.

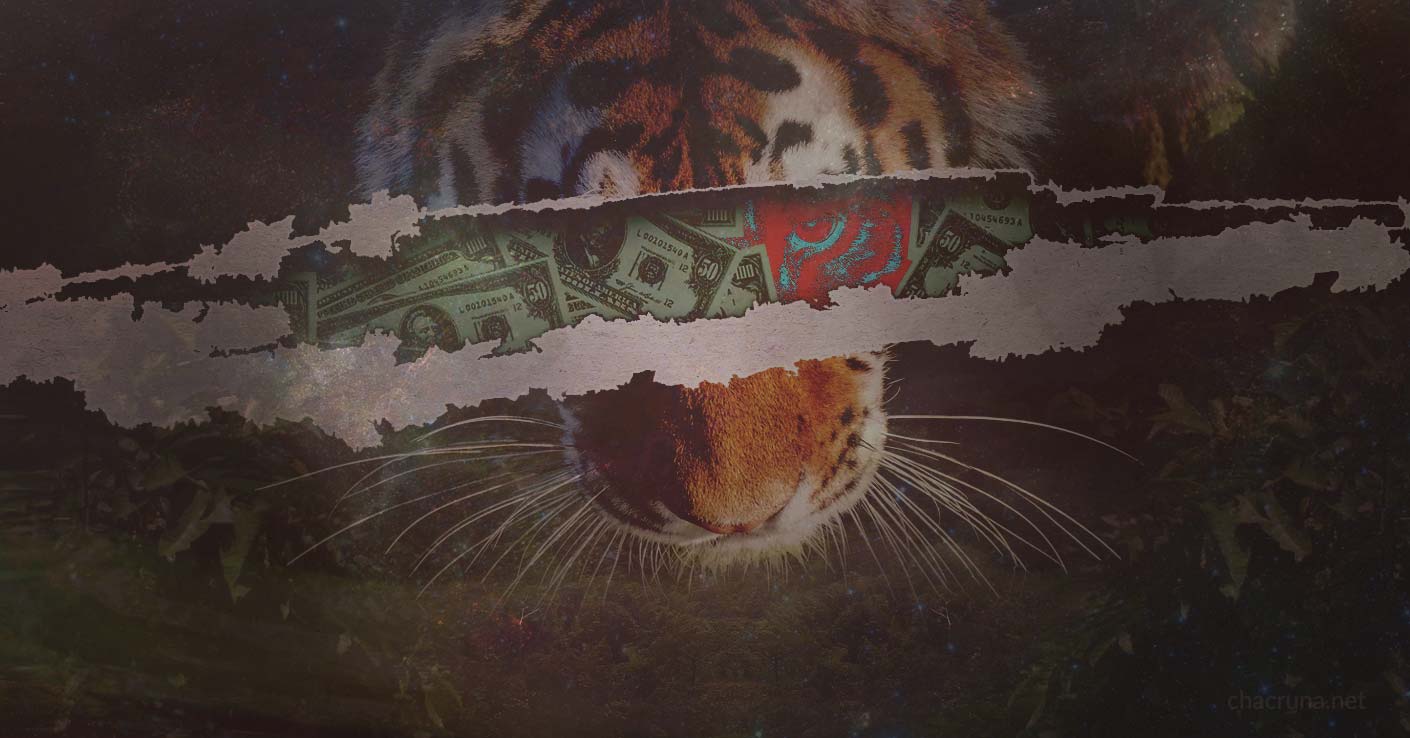

Formerly, the curacas were “tiger-men”: powerful medicine men capable of transforming into tigers, birds or reptiles. Today, because of environmental contamination, loss of knowledge, religions, war, plundering, and technology, these skills and other knowledge are in the process of extinction.

When there is harmony in the territories, the inhabitants of the community participate in the yagé ceremonies, contribute to the mingas (cooperative and voluntary work for the common good), respect the culture, and do not succumb to vices, drunkeness, family violence, and the extreme poverty of those who spend all of their income drinking excessively. The leaders of the cabildos who take yagé under the supervision of the curacas are less susceptible to the corruption that is prevalent in local government.1

Yagé medicine is our process of collective and individual spiritual healing. The ceremonies are sacred and social. Friendships are built; we laugh, analyze the problems, and find the solutions; we share knowledge and experiences. In the long nights of rituals, the fire and the sacred and powerful yagé plants of our forefathers illuminate our thoughts and clean our vision. There is also a lot of suffering; ancestral medicine is a process, with each person in his or her internal and sacred path, facing the difficult trials that yagé presents.

Only the elders, the curacas, the true holders of knowledge, can recognize illnesses and heal those possessed by malignant spirits. The others, the younger drinkers of yagé, are followers. We drink to improve as persons and spiritually. The medicine and the curacas help us leave behind our bad habits. We cry, we suffer, and we get up again, stronger. Indios live thus, learning to suffer; overcoming the trials life gives us. In order to learn and improve as a person, it is necessary to drink for many years, to continue drinking, and to grow spiritually, one little step at a time. This is the endless path of learning. The route of yagé is difficult and requires much personal care; it is essential to respect the norms and instructions given by the elders, the curacas.

Cultural Appropriation and Monetization of Ancestral Knowledge

People come: settlers or strangers, Whites and also Indios. Some come from the cities; we always receive them as friends, because the doors of healing are open to those who need it. They come to the territory, to the curaca grandfathers and put on feathers, sacred crowns, necklaces, rattling collars, and they look like tiger-men, taitas.2 The grandfather watches and remains silent. Then the medicine is distributed and the grandfather says that if the newcomers are crowned taitas, then we must drink as crowned taitas and he fills the cup to the brim. The grandfather, you see, has a naughty sense of humor. Then the suffering begins. The charlatans twist in pain on the floor, they cry, they vomit, they soil their pants; some ask the forgiveness of God. In the morning, very early, with nothing to say, they leave in silence. In ancestral medicine, it is necessary to learn respect towards the curaca elders, respect for yagé, and respect for oneself. One has to be humble before yagé.

People come: settlers or strangers, Whites and also Indios. Some come from the cities; we always receive them as friends, because the doors of healing are open to those who need it. They come to the territory, to the curaca grandfathers and put on feathers, sacred crowns, necklaces, rattling collars, and they look like tiger-men, taitas.2 The grandfather watches and remains silent. Then the medicine is distributed and the grandfather says that if the newcomers are crowned taitas, then we must drink as crowned taitas and he fills the cup to the brim. The grandfather, you see, has a naughty sense of humor. Then the suffering begins. The charlatans twist in pain on the floor, they cry, they vomit, they soil their pants; some ask the forgiveness of God. In the morning, very early, with nothing to say, they leave in silence. In ancestral medicine, it is necessary to learn respect towards the curaca elders, respect for yagé, and respect for oneself. One has to be humble before yagé.

Blind ambition for business and money foments bad practices and feeds the commerce of sacred medicine. There are members of the communities and also “Whites” who go about Colombia and the world wearing crowns and doing  commerce in yagé; some even call themselves taitas.3 They are people who do not have the knowledge and are not authorized by the true taitas or curacas to practice the medicine. It is sad, for this constitutes an appropriation of our ancestral practices, and it is lack of respect for our cultures, for sacred medicine, and for the curaca elders. Here, there are drinkers who are inhabitants of the cabildo who have been drinking yagé and practicing the medicine for years and years, whom we do not call taitas and who, out of humbleness, do not care to be referred to as such.

commerce in yagé; some even call themselves taitas.3 They are people who do not have the knowledge and are not authorized by the true taitas or curacas to practice the medicine. It is sad, for this constitutes an appropriation of our ancestral practices, and it is lack of respect for our cultures, for sacred medicine, and for the curaca elders. Here, there are drinkers who are inhabitants of the cabildo who have been drinking yagé and practicing the medicine for years and years, whom we do not call taitas and who, out of humbleness, do not care to be referred to as such.

Bad practices of yagé medicine offend the curaca grandfathers and cause serious problems such as rape, sexual assault, and even deaths. This harms the image of our communities and causes suffering and more illness in those seeking healing.4

The Territory

Our task as practitioners of the medicine and members of Unión de Médicos Indígenas Yageceros de la Amazonia Colombiana is to safeguard and strengthen the territory, to strengthen the culture and our self-government, and to strengthen the ancestral medicine that we inherited from our forefathers and remains heritage of the indigenous peoples and of humanity.5 Every time a hectare of territory falls in the hands of mining, logging or oil companies, or land grabbers, or drug traffickers, the indigenous communities and humanity lose ancestral knowledge that is essential for the survival of the peoples of the entire planet.

Notwithstanding national laws and international treaties that safeguard our cultures and territories, there are many pressures that put at risk the Amazonian life systems.6 The name of this plague scourging our territories is “extractive economy.” This is the social relationship that has historically linked our cultures with the “outside world.” The pillaging of resources: fauna, flora, minerals, hydrocarbons, people, and knowledge, as in the case of the pharmaceutical industry, and even extractive anthropology.7

Self-Government and Grassroots Organizations

The peace agreement between the government and the FARC guerrillas has meant an important step for our communities, historically victims of the armed conflict. It is also certain that now, new powers and economic interests, such as legal and illegal mining, drug-trafficking, and the hydrocarbons and livestock industries, among others, are advancing in taking control of territory with the aim of filling the gap left by the insurgency.

Hence, the importance of the process of strengthening grassroots organizations, indigenous self-government, the cabildos, rural associations and networks, and organizations of spiritual authorities, such as Unión de Médicos Indígenas Yageceros de la Amazonía Colombiana (UMIYAC).8

Self-government is the expression of the natural laws of indigenous communities. Through the construction of self-government and the strengthening of grassroots organizations, the indigenous communities fulfill their role of safeguarding the territories. This process is the response of the indigenous communities to the call of Mother Earth for reestablishing ancestral, spiritual equilibrium and a response to a “post-conflict” scenario, under which the assassinations of human rights and environmental defenders continue to increase.9

—————–

This article was translated by Leonardo Humérez and edited and revised by Riccardo Vitale. It is part of a larger publication written in Spanish and titled: Conversaciones entre Médicos y Seguidores del Yagé: Gobierno Proprio, Territorio y Conocimiento Ancestral. Available in http://neip.info/novo/wpcontent/uploads/2017/06/UMIYAC_Medicos_seguidores_yage_ALA_5_jun_2017.pdf

References

- The cabildos are indigenous political, territorial units recognized by the 1991Colombian Constitution, through Law 21/1991, which approves the adoption of International Labor Organization (ILO) Covenant 169/1989 on the rights of indigenous people. ↩

- Taita is the Kichwa word for father. The term, adopted by several Amazonian Indigenous groups, refers to elders who, after decades of practicing ancestral medicine, have earned the status of spiritual authority. Being called taita is a sign of great prestige. ↩

- Whites: persons not recognized as belonging to an indigenous ethnic group and who are not members of cabildos or communities. ↩

- As a reference, there is, for example, the case of Mister Edgar Orlando Gaitán, the “neo-shaman” accused in Colombia by the General Prosecutor’s Office of having raped and sexually assaulted up to 50 women, some of them underage. See also the case of Mr. A. Varela, of Ayahuasca International. This case gained international notoriety, generating an interesting debate on neo-chamanism and cultural appropriation. One hundred international academics prepared a letter supporting the Cofán people and denouncing the bad practices of Varela’s organization. ↩

- In Colombia, a Resolution of the Ministry of the Environment and Development, also of 2008, recognizes as a natural reserve the Flora Sanctuary of Medicinal Plants, Orito, Ingi Ande, in the Department of Putumayo. The same Resolution indicates that the practice of yagé medicine is a key element of the ancestral cultures of the Inga, Siona, Cofán, Kamentsá, and Coreguaje, and makes reference to the work of Unión de Médicos Indígenas Yageceros de la Amazonia Colombiana (UMIYAC) as the authority of tradition and self-government that works to preserve and revitalize the ancestral cultural practices of the region. ↩

- Reference to Covenant 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO) of 1989, adopted in its entirety by the Constitution of Colombia of 1991; United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of 2007; Sentence T-025 of the Constitutional Court of Colombia of 2004 and Resolution 004 of 2009. ↩

- The general feeling in the organization is that the relationship between academia and the indigenous communities has been historically one of imbalance and disadvantage for the latter. ↩

- Resolution 004 of 2009, follow-up to Sentence T-025 of 2004 includes the Inga, Kamentsá, Cofán, Coreguaje, and Siona peoples in the list of peoples at risk of physical and cultural extermination. Resolution 004 recognizes the importance of the relationship between territory, traditional institutions and self-government, autonomy and the resilience of indigenous peoples. ↩

- The People’s Ombudsman reports that, between January 1, 2016 and March 31, 2017, 156 social leaders and defenders of human rights were assassinated in Colombia. ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?

Become a Chacruna Member

To make a direct donation click the button below:

Wednesday, June 9th, 2021 from 12-1:30pm PST

REGISTER FOR THIS EVENT HERE

There is growing enthusiasm in Jewish communities about possible ancient use and modern applications of plant medicine in Jewish spiritual development. Psychedelic Judaism introduce new potential modes of healing...